To date, we have concentrated quite a bit on our High Culture and refined arts. But along with Maarga, there is also Desi. And along with Desi, there is a also Janapadiya. The Janapaadha Sangeetha of Andhra is often restricted to Burrakatha or Sankraanthi Haridhaasulu. However, there is much more beyond that.

History

“The author of the epic Mahabharata, Vyasa, said that Janapadas, meaning the common people, could be equated to scholars and even those who performed yajnas. The songs or poetical compositions sung by the people are folk songs and they form the bulk of folk literature.” [1, 93]

The Telugu Language features literature that spans Graanthikam (Scholarly), Maandalikam (Urbane), and Jaanapaadham (Country-speech). The great Gidugu Ramamurthy Panthulu gaaru popularised Vyavahaarikam (regular speech) as a compromise to appeal to all 3 segments. Jaanapaadham is known for its colloquialisms and colloquial songs (geya).

Therefore, while it is important to first establish the sophisticated traditions of orthodox Aandhra music, it is also imperative to protect the colloquial and the rural. The expressions of the country-side often feature this balance of desi and maarga.

“Telugu literature is divided into two major sections, known as the marga and the desi. The first is always attributed to an author and comprises classical poetry, while the other is the expression of the heightened emotions of a community recorded for posterity. There is little similarity between the two. The poetry of the elite has the grace and artistry of urbane expression. Folk poetry has a natural, earthy fragrance.” [1. 93]

“The Gatha Sapta Sati of Hala tells us of the joyous song of a peasant when he sees his crop-laden field. Chalukya Somesvara III tells us in his Abhilasithartha Chintaamani that ‘Shatpadi’ metre was used for story-tellings“. [1, 107]

Indeed, Andhra has historically excelled at this balance of both the refined and the popular. Rather than being over-refined and disconnected from the masses, it has managed to effectively bring High Culture to the masses via the vehicle of Mass culture. Folk culture also has its place in any desa or pradesa. An over-sophisticated culture of stifling fops repels the vigorous aspirations of the people for expression and exhilaration.

“folk is a comprehensive word. It suggests a whole nation or a huge concourse of people. In this tract of the Telugu land such people have been living for centuries. They live a community life; the trials, tribulations and joys of human living are common to them all. Folk lore includes myths, tales, beliefs, superstitions, customs, manners, sorcery and magical practices, philo-sophic knowledge, proverbs, plays, festivals and several other related matters, which have a bearing on the lives of the people.” [1, 94]

“Literary critics have confirmed the opinion that songs, ballads and lyrics held sway before the birth of classical literature. It is always during moments of passionate exhila-ration and emotion that the people, men and women, begin to sing and dance and music are improvised for the purpose. In the texts of those songs, we do not find either ornateness or literary flourishes.” [1, 94]

There are many theories about what came first, the chicken or the egg. There are those who would emphasise that it is Saasthra which was revealed first by the Divine. Others take a more anthropogenic view of things.

“A song or rhythmic pattern of words is improvised by some one and the same is repeated by many in chorus. This is how folk poetry originates. The song is then registered in the memories of the people. The community holds to the treasury of songs.” [1, 94]

Folk metres were commonly utilised by the stalwarts of yesteryear.

“The pre-Nannaya inscriptions indicate the existence of some metrical compositions, akin to folk metres. Nannechoda in his Kumarasambhavamu made a reference to Ankamalika, Gaudugitamu, Rokati Pata and Uyyalapata, which are folk songs. Palkuriki Somanatha mentioned more than a dozen folk songs in his work Panditaradhya Charita. He also ac-knowledged in his Basavapurana that the source of that poeti-cal work was actually the old folk songs dealing with the exploits of Basava.” [1, 96]

Demonstrating the symbiotic nature of classical and folk, vaaggeyakaaras such as Annamacharya drew much from jaanapaadha sangeetha. Laalipaatalu in Telugu is one such devotional song category and it is sung in Navaroju raaga.[1, 113] His grandson, Peddha Thirumalachaarya, laid out the metres and principles of composition for ‘Ela’, ‘Gobbilu’, and ‘Chandamama Patalu’, which demonstrates the seamless connection between folk and Classical Carnatic Music. [1, 97]

Characteristics

Native Indic Music has historically been divided into 3 categories. Per the Brhaddesi of Matanga Muni they are as follows: Maarga, Desi, & Jaanapaadheeyam. In the present era, many efforts have been made to show that the spiritual music of maarga stifled desi and janapaadha music. But nothing can be further from the truth. In fact, all three were complementary. Maarga presented the spiritual core, desi represented orthodox but innovative form for free-spirited artists, and jaanapadha was the lovely, earthy, popular music of the common man’s minstrel. [2] Alaapana (melodic elaboration) was the key differentiator between maarga and desi.

Maarga—The Four Vedas, along with the Sapta Svaras, are called Maarga and are considered to have come from Deva Loka.

Desi—Also described as the Desi course of Maarga by Matanga Muni, this category embodies the spiritual nature of Maarga with regional influences. Thus, Carnatic Sangeetha is the best example of this due to its use of saptha svara and attachment to Vedas, but with raagas common to Karu desa and the rest of the Dhakshinapatha.

Jaanapaadheeyam—This is pure desi music. This means it is bottom-up, grassroots music wholly derived from the countryside. Its themes may run the gamut, but are inclusive of the spiritual. It can be sub-divided as follows.

Suddha—Singing within established frameworks of ascending and descending notes. In the traditional manner.

Salaka—Singing purely per ones whims, without any traditional guide or structure.

Vinodham—This is music completely dedicated to entertainment. It too is found in nibaddha and anibaddha forms. It is not noted for spiritual themes, and is the category best suited for musical forms that are mundane, vulgar, or foreign-influenced (sometimes the two are one and the same…). Indeed, often clubbed under desi, the javalis of yesteryear are considered vulgar and are better suited for this category, as Saasthra considers such themes as inappropriate for general audiences.

By ensuring that Maarga and both forms of Desi remain uncorrupted, modern musicians may freely perform collaborations on the world stage with foreign musicians via vinodham. In the process, tradition remains pristine whilst international creativity remains unstifled. It too may be structured or unstructured, and open to experimentation and free-form. Rather than under desi, Hindustani may ultimately be more suitably categorised under vinodham as its foreign-influence is pervasive and for entertainment purposes.

The interplay between the Suddha and Salaka forms of Jaanapaadheeyam make it most intriguing even to the most snooty of sahrdhayas (connoisseurs).

“These two forms of folk music representing joyous self-expression at one end and auxiliary music helping the narration of a story at the other, are undoubtedly the two extremes of folk music. The first uses the pleasing and sonorous notes of the natural musical scale (Sa, Ri, Ga, Ma, Pa, Da, Ni and Sa…), to the exclusion of the time-keeping sense, while the other plays second fiddle to the run of the story by providing a smooth sonorous beat. Time-keeping must have been very faithful in the second to make up for the sparse use of music as such. Folk music ranges between these two extremes.” [1, 107]

“In the first type there is more room for word play and there is also the introductory Laya (rhythm) of an elementary type. In the second type Dhruva, Pallavi, Charana etc. are introduced wherein are repeated se[t] patterns of svara (tone) metrics, which in turn carry a set rhythmic structure”. [1, 107-108]

Folk music, or Jaanapaadheeya Sangeetha is often alternately divided into 4 types:

- Solo music by a worker or peasant doing his chores in the fields or forests

- Solo repertoire leading a song joined by a chorus of labourers

- Child singing before a group

- Balladeer or story-teller singing before a group

The last of these categories is particularly prominent. This is because the great deeds of royal dynasties or puraanic figures are often sung by such personages. Haridhaasulu naturally fit in this type as well.

Other notable types of songs are those sung by a mother conducting her duties, a lady singing story-poems for a marriage and the like, and individuals singing during a play.

“Music is made by agreeable permutations or garlands of svaras; and five or more svaras in the Arohana (or Avarohana) constitute part of a raga.” [1, 108]

“Folk music becomes music by virtue of the musical notes (svaras) it uses and by virtue of the laya involved…Folk music, at its best, is expressive and holds the audience by a flow of sonorous notes and rarely does it aim at art.” [1, 109] In essence, rather than aiming at technical perfection or refined artistry, bhaava (feeling) is itself the goal.

Jaanapaadheeya Sangeetha, unlike Saasthreeya Sangeetha, is more free and less regimented. Yet, Bharatha Muni provides for it, along with Desi and Maarga. As Matanga Muni establishes, Desi is not folk music, but rather, is regional variations of Maarga. Jaanapaadheeyam is folk music, and therefore, is more quotidian. It can be as simple as tapping one’s foot and humming a tune, or be far more complicated and aesthetically practiced.

Jaanapaadheeya Sangeetha is characterised by:

- Tone of voice and distinct sweetness

- Chorus to increase resonance

- Svaralapa that precedes or follows a folk song

- The folk song frequently features an instrument such as thamboora or karathaala

Well known marriage songs sung by ladies include ‘Seetha Mudrikalu’ and ‘Raghava Kalyanam’.

In general, folk songs run the gamut. These included puraanic, historical, religious or simple sentiments (rasa). They are often punctuated by exclamatory phrases such as “Aha ha ha” and “Oh ho ho“. [1, 111]

“At times, when a minstrel wanders about begging, the husband sings in ‘Madhyasthayi’ and the wife in ‘Tarasthayi’. Even here the difference is only in the sthayi, i.e. pitch and not in the sruti.” [1, 112]

“Two svaras are heard prominently in the endings of lullabies. They are usually ri and sa. The ri lifts the drowsy mind to an artificial height, the sa brings it down. Often the two svaras accompany the ‘jo jo’ expression at line ends. It is interesting to remember that the Gathas of Hala in their original Prakrit very probably continued this double svara in the line ends, and hence gave their name to this pleasing pair. This must be the ‘Gathika’ of music treatises.” [1, 109]

There are numerous lullabies that have attained great fame in the Telugu tradition. Many have featured even in the mass, masala entertainers of yesteryear.

Topics range from putting a child to sleep (as intended above) or singing about legendary stories from popular tales to comforting a child. Whether structured or unstructured, some patterns remain apparent.

“Three svaras are heard in the morning song of the mother churning curds. They accompany the end word ‘Oh, wake up’ (meluko) in a crescendo so as to coax the sleeper to wakefulness with the repeated musical taps on his ears. This is the ‘Samika’ of the treatises…This triple combination is present in the folk music of all the provinces of India.” [1, 109]

“Svarantara is a group of four svaras. We hear it especially in the pseudo Anupallavi of women’s songs. It is very con-venient for a singer to sing in the medium scale (madhya sthayi) but the notes of the higher pitch (tara sthayi) have their attraction. A flight into the higher pitch by a lady singer usually shows the svarantara. The mangalam or song of benediction invariably shows a svarantara.” [1, 109-110]

Incidentally, for those who like to classify all four southern states under ‘Dravida’ due to ‘Jana Gana Mana’, ancient Matanga Muni in listing his varieties of Desailaa clearly distinguishes the two. In fact, for our regional champions, he lists the following regional styles of Bhaarathavarsha:

- Laataila (for Laata, i.e. Southern Gujarat)

- Karnaataila (for Karnaata)

- Gaudaila (for Gauda, i.e. Bengal)

- Aandhraila (for Andhra)

- Dravidaila (for Dravida, i.e. ancient Tamizh Nadu and Kerala).

[2, xvi]

The cultural prominence of these regions, whether Gujarat & Bengal or Andhra & Karnata were seen even in Matanga’s time. Regardless of region, however, commonalities remain apparent.

“Music is the anupama for the sentiment or rasa of the story. So whether a song is composed in shatpadi metre of Khanda gati, the various lines of the composition are rendered in an identical succession of notes. When put together, the notes certainly make a svarantara with ni, sa, ri, ma and pa svaras showing themselves in garlands.” [1, 110]

“The love songs of the peasants would reveal that occasional excursions into a raga were known, but they were not the order of the day. The rendering of svaras in a pleasing way is the keynote of the folk music of Andhra. The Janapada is now worried about showing his skill; he performs for the benefit of others, and the svara presents itself in his music with the full import of its generic meaning.” [1, 110]

“The people are not tired of repeating the same cadence, their aim being to bring some joy to work, to forget the boredom of work, and to render a story palatable. And in these repetitions, the svaras make the nerves vibrant enough to shake off the fatigue of unusual exertion.” [1, 110]

Nevertheless, there are some aspects of country-side music that do stand out. What is deemed anathema in the orthodox may add flavour in the unregimented.

“Folk music is tolerant of disso-nant notes, but does not love them nor does it introduce them deliberately.” [1, 110]

“Laya or the regularity of steps attains its maximum accuracy in group music. A number of singers join in a circle and provide a happy background to the narrator of a story.” [1, 110]

More than sentiment, it is energy and ebullience that punctuates the the people-at-large. While there are songs for sorrow and serenity, folk music is untrammeled by etiquette and pursues the pleasing. The worker who has spent his day toiling in the fields feels relieved when he is uplifted by the simple and scintillating.

“The group keeps time with wooden cymbals, steps forward and backward to narrow down the circle and widens it and sings the burden of the song when the story is smooth…Often the ‘ektal’ is employed and occasionally ‘triputa’ with its seven units shows itself and the smooth journey on the rhythm of the infectious beats continues to entertain the thousands that throng round to spend their nights joyfully.” [1, 111]

“The drum as an accompaniment is seen sometimes, but it plays the simple laya and not all the complicated matrices shown on platforms in music sabhas (assembly).” [1, 111]

Beat’s primary premise in folk music is to capture the attention and resonate with the audience. In the process, ideas and tales can be communicated.

Tala (thaala) refers to the beat that tracks time (Kaala) and determines tempo (Gathi ) and rhythm (Laya). It is the backbone of any composition. There is a saying that Sruthi (pitch) is the mother of music and Thaala (beat) is the father. There are 7 basic thaalas: Dhruva, Matya, Rupaka, Jhampa, Triputa (Adi), Ata, and Eka. When these are combined with the various jathis, were get 35 thaalas. When joined with gathis, the total reaches 175. Layam indicates the rhythm of the thaalam, and there are 3 kinds (Vilamba, Madhya, Duritha). [2]

“Tala, like svara is intended as a harmonising influence on the audience. The story is all. There is no music without a story…proof that people are not interested in intellectual exercises. They enjoy rhyme and rhythm, but not a show of the talent of an individual on a musical instrument.” [1, 111]

“The basic difference between classical music and folk music is more in the spirit than in the outward form. Folk music is born of the rustic’s heart, whereas classical music is the product of the thinking mind of elite musicians.” [1, 111]

Varieties

“In various regions (dhvani or manifest sound) spontaneously becomes pleasant to living beings and starting with them (it is also pleasant) to the people and kings. This dhvani that arises from region to region is called desi (born in or proceeding from various desas or regions).” [5,1]

Contrary to modern “Art Music” opinionistas, Indian music goes beyond Sacred music and already includes an Art Music (called Vinodham) and “Art Musical Forms”— Padam, Javali, and Thillana. Others forms include, Kalakshepam (singing of epics/Harikatha), Dance musical form, Opera musical form (Yakshagana), Secular music (songs on Niti, such as those by Siddhars), Folk Music (Jaanapaadheeyam), Martial Music (Veera), Kalpitha music and Manodharma music (no prior preparation).

In the section on prabandha, there Matanga Muni mention of the nature and characteristics of the Karnaata language (i.e. Kannada) itself. [6, 215] The ashta-rasa of Bharata muni are also listed. [5, 49] He proceeds with the text by stating the following:

“From the vaakya (sentence) (arises) the mahaavaakya (lit. big or great sentence) and in succession (arise) the Vedas with their angas (ancillary disciplines); all those are manifested from dhvani. From there (Vedas) is the origin of Gaandharva (music).” ch.1, sl.11 [4, 117]

Another point of interest is Dattila’s reference to various regions and musical aspects attached to regions. He makes frequent mention of jatis called udeecyava (meaning from the north), and also refers to Aandhri (Andhra), Takka raaga (from NW Punjab), Maalavi (from Malava/Malwa), Kamboji (from ancient Kamboja), Gaudi (from Gauda/Bengal), and Gandhaara jatis, in verses 70-79. [4, 117]

As such, each region not only produces or can produce its own desiya sangeetha on the urbane end, but also folk music at the jaanapaadheeya end. In Aandhra’s case, one name stands out for standardising many of these folk songs. Avarsarala Anusuya Devi (nee Vinjamuri) is credited with recording the most prominent numbers of the janapaadha sangeetha repertoire.

“What began as a hobby has become my profession and passion,” says the spirited lady who released five volumes of her collection of Telugu folk songs at an informal function organised by her children (including dance guru Rathna Kumar and Sita Ratnakar of DD).” [7]

These five volumes of song from the country-side run the gamut: Laali Paatalu, Mangalahaaratulu, Panduga Paatalu, Sthree Paatalu, Samvaadhala Paatalu. Her life story itself is a testament to this intrinsic and symbiotic connection between spiritual (maargiya) and folk (jaanapaadheeyam). “For the author, these books are a result of a lifetime spent collecting and notating songs from every source possible… villagers working in the fields, mendicants and sometimes, even beggars! For somebody whose first recording was released when she was just eight, music was naturally an inseparable part. Born into a family of poets and musicians (father was a Telugu-Sanskrit scholar, mother launched Telugu’s first women’s magazine and uncle Devulapalli Krishna Sastri was a renowned poet)“. [7]

As such, despite coming from an orthodox background, she preserved the songs that symbolise the soul of the Telugu people, for posterity.

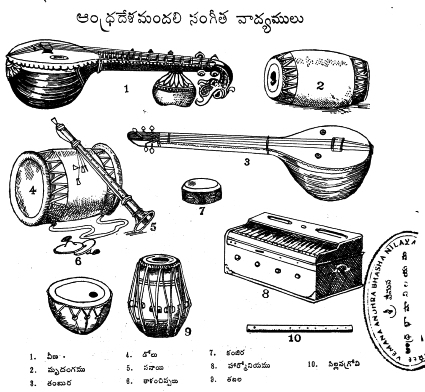

Instruments

The Musical instrument (Aattodya or Vaadya) [2,110] in Carnatic music is of four kinds: Thatha vaadhyam, Sushira vaadhyam, Avanattha vaadhyam, and Ghana vaadhyam. “They are respectively called stringed instruments, thulai (hole) instruments, leather instruments and metal instruments.”[1, 97]

Bharatha muni wrote further establishing the instrument as part of Sangeetha itself:

Geetham vaadyam thathaa Nruthyam-thrayam sangeetham ucchyathe ||

Sangeetham comprises Geetham, Vadyam and Nrutthyam [2]

Given the essential nature of vaadhyam to jaanapaadheeyam, a deeper dive is required to gain a better understanding of their varieties, their distinctiveness, and yet, their connection to the wider civilization-at-large. The first of these is that celebrated membranophone: the drum.

The Damaru and Dhundubhi are famed drums from the Saasthreeya Sangeetha tradition. Even today, one finds notable percussion accompaniments in Carnatic music via the mrdhangam and the ghatam. However, there are others who put the egg before the chicken.

“The musical association of drums starts however with primitive dance-music rituals. Even today, the great variety of folk drums are nrityanuga—i.e., accompaniments to dance.” [8, 59]

“Sabdarathakaram, the Telugu dictionary says that Tappeta, Tammata and Dappu are synonyms to each other…Tappeta consits of a leather held taut in a round wooden frame. It produces high sound. Usually the Tappeta is hung from the left shoulder of the artiste with a slightly thick stick in the right hand, a leaner and smaller stick in the left hand…During festivities and processions Tappeta is nor-mally employed. Tappeta is used in villages to attract people to listen to public announcements.” [9, 167]

The Tammata is similar but smaller in size, and it is hand-held rather than shoulder-held. In Samskrtham, it is known as ‘Lambapataha’. [9, 168] The Chandravalayam is even smaller in size, and has iron rings affixed to it to producer a simultaneous membranophonic and metallic percussive. It is often compared to the Kanjeera [9, 168]

“Drums have not always been of musical use; the ranabheri, for instance, was a martial instrument and the village announcer with his strident duff is a well-known figure to us.” [8, 59]

“A typical folk drum of south India is the pambai (Tamil) or pamba (Telugu). This is really two cylindrical drums tied together and the pair is called the pambai. The drums are about 30 cm in length and 15 cm in diameter. The membranes of goatskin are held by means of metal rings which are tied together by rope…The drums are beaten with thin curved sticks, often of betel tree.” [8, 73]

“The burburi of Andhra and Karnataka is a bifacial cylindrical drum” which is used by a community of folk deity worshipers who place an icon of the deity on their heads, going door-to-door for alms. This friction drum is hung from the neck and hit with a stick on the side. [8, 84]

Among wind instruments, there is the kaahala, which was a brass trumpet, shaped like a thin and long horn. “In ancient times Kaahala was played to indicate the passage of time and special staff was employed to do this. During nights in some places Kaahala was blown to indicate ‘Particular Times’. It is used in worship, pro-cessions and other functions of temples.” [9, 176] It is alternately known as the narsingha in other parts of India. A related instrument is the kommu, which has the same Telugu name as its base material (animal horn). It was used as a trumpet not only by folk musicians, but even by members of the royal hunt. The true trumpet, was made of brass, and was generally around 115 cm. [8, 95]

The famous venu of Saasthriya Sangeetha finds its place in Aandhra with the more minute Pillanagrovi. This wind instrument finds its place among young and old alike. [8, 91] The Sankha (conch) is one more wind instrument. This one is famed for its puraanic versions, and it too is used in temple festivities for ceremony and pomp, and of course, battle.

The Pungi is a folk variant of the Naadhasvaram, and is the tool of the snake-charmer’s trade. It too is made of reed, but has only one, while the latter has two. [8, 99] ‘The Bagpipe’of Folk Music was the Titti (which is the Telugu word for Bag). Unlike the Pungi, the reservoir is not made from gourd, but rather, is formed from goat-skin. Two bamboo tubes are passed through, and a metal pipe with six holes is placed on the top. [8, 101]

“There is a class of folk instruments, closely resembling the tuntune but essentially rhythmic in function. These are the prem tal of upper India, the chonka of Maharashtra and the jamuku of Andhra…the resonator is a hollow bottle gourd, a wooden or metal cylinder…The instruments are rhythmic, because the sounds emanating are vague and indefinite in pitch“. [8, 134]

Among plucked instruments is the fingerboard instrument Kinnari, common throughout India. In Aandhra there is also the khingri, which is a bowed instrument proper. [8, 30] Ghanta (metal bell) and gajjelu (ghungroo or noopoora, anklet bells). Interestingly, the Chenchu Tribals wear a waistbelt (gilabada) version of clasped bells. Small dried beans are often used instead. [9, 44] The famed all-India karathaala is called chekkalu among Telugu folk singers.

“Tipiri Dande is a variant of Veena which can produce sounds in the three octaves“, and it is mentioned by both Palkuriki Somanath and Annamayya. [9, 154] Kacchapi is another such string instrument. It was mentioned by Haripala in his Sangeetha Sudhaakara. A picture of it can be found in the sculptures of Naagaarjuna Konda (200 B.C.E.). “Kacchapi is almost akin to the modern Sitar.” [9, 160] Others may compare it to the chithra veena.

There are, of course, many more folk instruments—Aandhra specific and All-INdia—that can be discussed. For now, this suffices. Of greater import is the future of Folk Music in the Telugu States.

Future

Like much of Aandhra and Indian culture in general, the future of Janapaadha Sangeetha remains bleak. Widespread drives to ‘modernise’ and ‘globalise’ have resulted in prioritising the English Language over the native Telugu. How can traditional rural forms be expected to survive when the native population can barely speak its own language?

From the burrakatha performer to the haridhaasu, and to everyone in between, the songs of our ancestors remain with or without literacy—so long as they are sung.

Language is culture, whether the salary-man accepts it or not. It is long past time people wake up to their obligations to preserve genuine traditions that uplift and inspire.

“The natural simplicity and the glow of the human heart, so evident in the rural folk, form an important aspect in the style and form of folk music.” [1,111]

References:

- Raju, B. Rama. Folklore of Andhra Pradesh. New Delhi: NBT. 2014

- Sharma, Prem Lata. Brhaddesi of Sri Matanga Muni. Vol. II. New Delhi: IGNCA. 1994

- Iyer, A.S. Panchapakesa. Karnataka Sangeeta Sastra: Theory of Carnatic Music. Chennai: Ganamrutha Prachuram.2008

- Lath, Mukund & Ed. Kapila Vatsyayan. Dattilam. Delhi: IGNCA.1988

- Sharma, Prem Lata. Brhaddesi of Sri Matanga Muni. Vol. I. New Delhi: IGNCA. 1992

- Sharma, Prem Lata. Brhaddesi of Sri Matanga Muni. Vol. II. New Delhi: IGNCA. 1994

- “The Grand Dame of Telugu folk songs”. The Hindu. (Jan 29, 2010) https://www.thehindu.com/books/Grand-dame-of-Telugu-folk-songs/article16840318.ece

- Chaitanya Deva, B. Musical Instruments of India-Their History & Development. New Delhi. Munshiram Manoharlal. 2014

- Kusuma Bai, K. Music-Dance and Musical Instruments—During The Period of Nayakas (1673-1732). Varanasi: Chaukhambha. 2000