The next instrument in our Continuing Series on Carnatic Classical Instruments is one which is as familiar to bhajan singers as it is to skilled Kacheri performers. It is one which brings a jingle and twinkle to listeners lay and professional alike: Kanjeera.

Introduction

As stated previously, the Musical instrument (Aathodhya or Vaadhya) [2,110] in our Classical Indic Music is of four kinds: Thatha vaadhyam, Sushira vaadhyam, Avanatta vaadhyam, and Ghana vaadhyam. “They are respectively called stringed instruments, thulai (hole) instruments, leather instruments and metal instruments.”[1, 97]

In tandem with the categories stated above are a horizontal set of divisions. These are Sruthi, Sangeetha, and Laya

“Sruthi Instruments: Ta[m]bura (Thatha) – Otthu (Sushira), Sruthi box (Sushira).

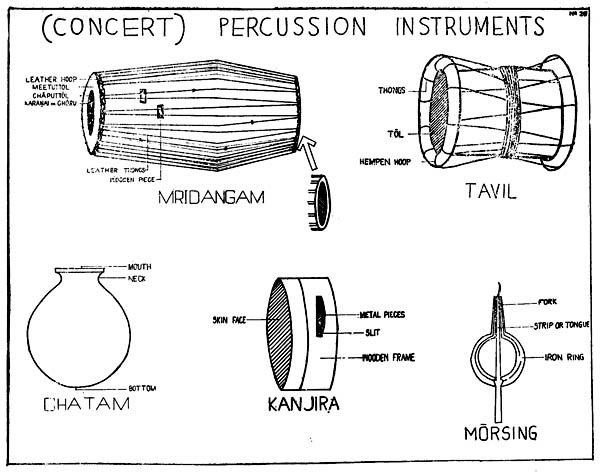

Sangeetha Instruments: Veena (Thatha), Gottu (Thatha), Violin (Thatha), Flute (Sushira), Nagaswaram (Sushira), Harmonium (Sushira), Jalatarangam *Water is poured in [por]celain cups and then played by sticks). Laya Instruments: Mridangam (Avanatta), Thavul (Avanatta), Keethu (Thatha), Moorsing (Gana), Kanjira (Avanatta), Ghatam (Mud pot), Jalar (Gana)-Bronze).” [1, 97]

Arguably the only outlier is the Ghatam, which is a percussion instrument. In light of that, a better series of equivalents has also been proposed by others. That is, chordophones (thatha), aerophones (sushira), membranophones (avanatha), and ideophones (ghana). Ideophones are any solid instrument, without leather coverings or other membranes. The clay ghatam, would therefore be correctly classified under ghana vaadhya. Non-classical instruments which have now become part of the modern Carnatic repertoire are the western imports such as Violin, Harmonium, and Sruthi Box (alternately known as electronic Tambura).

History

“Maanpoondiya Pillai (1859-1922) who designed ganjira and established the Pudukottai school of playing percussion instrument was a labourer assigned with the task of lighting the lanterns in a palace.” [5]

The history of the Kanjeera begins with the different types of single-frame drums. The first type has a large frame and is made from buffalo hide (like Karnataka’s halgi). The second is smaller (between 20-40 cm) and has some slits in it. These are called khanjari. Finally, the third is even smaller and is 15-20 cm. The skin is often the hide of a lizard, such as an iguana. This is called kanjeera.

“While almost all of the frame drums are used in tribal and folk music and dance, the kanjeera has become a concert instrument in Karnatak music. Here it is not the principal accompaniment, yet it is an effective auxiliary to the mridangam and the ghatam.” [3, 64]

The standard name for this vaadya is Chandravalayam. In Andhra, it is called Tammata.

“It is round but smaller in size [to the Tappeta].This is also beaten by hand to give ta:la support to music. It’s employed in Bhajans very often. Small metal rings number-ing about three or four are fixed at suitable intervals in the frame and whenever the Candravalayam is beaten, these rings make a sound similar to the sound produced by ankle bells. This is also known as Kanjira in North India.” [2, 168]

Once an all-India instrument, the Kanjeera is more commonly associated with the South, in the present time. Most uniquely, it is used in august formal Carnatic performances, which is surprising considering its foreign equivalent tambourine is typically relegated to informal musical ensembles. And yet, in spite of its modest reputation, there is a skill in not only playing a kanjeera, but making one.

Characteristics

The kanjeera is a stand out among the already stand out class of percussion instruments known as frame drums. It is easy to use and easy to carry. Incisions are made on the side of the frame to fit metal discs, typically of brass. The leather too is also of a more eye-catching variety, in contrast to the more pedestrian ungulate skins. While iguana and monitor lizard were the traditional membranes used, due to current environmentalist efforts, goatskin is now being encouraged.

Interestingly, many modern versions of the kanjeera keep the metal discs contained within the drum itself. This provides for more rapid riffs on this rhythmic instrument.

Process

This athodya, like many others, is typically made from jackfruit wood and leather.

In the present time, there is an anecdote that informs the creation of the modern kanjeera, which is often called ganjeera. Interestingly, a mrdangam artist suggested an amateur aficionado develop an instrument:

“This prompted Maanpoondiya Pillai to create ganjira, a small instrument with a 6.5 to 7 inch width. He used the skin of monitor lizard to produce the unique sound and fixed old coins to embellish the playing. Rice paste or fenugreek paste is used to fix the skin on the drum.” [5]

Thought this may account for its present form, it is in fact an ancient instrument that is most commonly used in unstructured (anibandha) musical performances.

Legacy

The Legacy of the Kanjeera is as interesting as the philosophy informing it. While on the outside it appears ideal for virtuoso instrumentalists and even beatnik or beat-boxing artists, more traditional savants advocate a different approach in popularising its revival.

“Ramachar gave a lecture demonstration on the kanjira at the Indian Fine Arts Society on December 23. Tracing the history of the instrument over the years he recalled how veteran rhythm masters like Dakshinamurthy Pillai had handled the instrument. He emphasised that the kanjira artiste should play softly and in unison with the mridangam – the kanjira ideally should not be heard separately from the mridangam.” [4]

Although the low-key nature invites marginalising of the artistes, who are accustomed to being accompanists, a number of exponents have raised the profile of this vaadhya. The introduction of kanjeera to the modern carnatic kutapa is credited to Maanpoondia Pillai.

Famous Players

Maanpoondia Pillai

Trichy Sankaran

Dakshinamurthy Pillai

G. Harishankaran

Mayavaram G. Somasundaram

H.P. Ramachar

Latha Ramachar

Bangalore Amrit

C.P. Vyasa Vitthala

N. Ganesh Kumar

B. Shree Sundarkumar

B.S. Purushottam

Selva Ganesh

Despite the unassuming nature of the kanjeera, it is as much an instrument of the formal as it is the informal. As the present ganjeera of Manpoondia Pillai shows, it is also as much an instrument of yesterday as it is today. So grab a kanjeera and learn on your own!

References:

- Iyer, A.S. Panchapakesa. Karnataka Sangeeta Sastra: Theory of Carnatic Music. Chennai: Ganamrutha Prachuram.2008

- Bai, Kusuma K. Music-Dance and Musical Instruments: During the Period of Nayakas (1673-1732). Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrit Bhawan. 1999

- Deva, B. Chaitanya. Musical Instruments of India: Their History and Development. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publ. 2014

- ‘Soothing Notes from the Kanjira’. The Hindu. December 29, 2000. https://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/2000/12/29/stories/0929070q.htm

- ‘The Sound Challenge’. The Hindu. January 14, 2016. https://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/The-sound-challenge/article13999469.ece