Continuing our Series on Carnatic Classical Instruments is an athodya that sets the rhythm of the margazhi season night. After preceding articles on the Veena and the Venu, is today’s post on a vaadhya that doesn’t always get its due.

The next Installment covers an instrument that should be part of virtually any classical ensemble: Mrdangam.

Introduction

As stated previously, the Musical instrument (Aathodhya or Vaadhya) [2,110] in Classical Indic music is of four kinds: Thatha vaadhyam, Sushira vaadhyam, Avanatta vaadhyam, and Ghana vaadhyam. “They are respectively called stringed instruments, thulai (hole) instruments, leather instruments and metal instruments.”[1, 97]

If veena fits the first category and venu the second, then mrdangam fits the third. Avanatta instruments are made out of wood (or clay) and are typically covered with leather. They can be played by hand or stick.

In tandem with the categories stated above are a horizontal set of divisions. These are Sruthi, Sangeetha, and Laya

“Sruthi Instruments: Ta[m]bura (Thatha) – Otthu (Sushira), Sruthi box (Sushira).

Sangeetha Instruments: Veena (Thatha), Gottu (Thatha), Violin (Thatha), Flute (Sushira), Nagaswaram (Sushira), Harmonium (Sushira), Jalatarangam *Water is poured in [por]celain cups and then played by sticks).

Laya Instruments: Mridangam (Avanatta), Thavul (Avanatta), Keethu (Thatha), Moorsing (Gana), Kanjira (Avanatta), Ghatam (Mud pot), Jalar (Gana)-Bronze).” [1, 97]

Arguably the only outlier is the Ghatam, which is a percussion instrument. In light of that, a better series of equivalents has also been proposed by others. That is, chordophones (thatha), aerophones (sushira), membranophones (avanatha), and ideophones (ghana). Ideophones are any solid instrument, without leather coverings or other membranes. The clay ghatam, would therefore be correctly classified under ghana vaadhya. Non-classical instruments which have now become part of the modern Carnatic repertoire are the western imports such as Violin, Harmonium, and Sruthi Box (alternately known as electronic Tambura).

The putative etymology of the mrdangam is an interesting one. It is said to be a portmanteau of mrt (‘clay’) and angam (‘limb’, or sometimes ‘body’). This is because the earliest versions are thought to have been made from clay. A variation of this is that the term comes from mrdu (‘soft’) angam (‘part’) due to the leather coverings on either end.

Nowadays, the panasa (jackfruit) wood serves as the base of the drum, with leather covering the sides.

History

The mrdangam is rhythmic instrument that is at the heart of Classical Carnatic. Alternately called the pakhawaj in the North, it is an ancient percussive piece that continues in use to this day. It is related to the damaru. It is considered by some to be the King of Percussion instruments.

“With mridangam came the evolution of the South Indian tala system, perhaps the most complex percussive rhythmic system of any form of classical music. Mridangam is a percussion instrument with Sruthi.” [4]

Some have attempted to attach a regional colour to the mrdangam, but this is improper given its attributed divine origins, as noted above and below.

“ORIGIN OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS:

bharata narrated the story of the origin of various instruments thus: Sage svaati went to a lake to fetch water on a holiday when it was raining heavily. The torrents of rain, fast as wind, falling on the lotus leaves in the waters of the lake, excited the birds which produced inexplicable sweet sounds. svaati was astonished at the rich melodious sounds made by the falling water drops and the low, the medium and the high notes produced by the birds. He went back to his hermitage and pondered over the possibility of producing musical instruments incorporating these sounds. He sought the assistance of viSvakarma, the celestial architect, and constructed various drums including mridanga, paNava and dardura.” [2, 111]

These instruments were either taught with strings or covered with leather. “He also constructed jhallari, paTaha, muraja, aalingya, uurdhvaka and ankika bearing in mind the pattern of the celestrial drum, dundubhi. The highly creative and imaginative svaati further constructed several instruments in wood and iron“. [2, 112]

This is where the story becomes interesting as numerous variations of instruments are described. While vipancii and chitra varieties of veena were considered major instruments, kacchapi, ghooshaka were considered minor. Most notably, however, were the percussion instruments. “Among the percussion instruments, the tripushkara or the three drums viz., mridanga, paNava and dardura are the major instruments and hallarii, paTaha etc., are the minor instruments.” [2,112]

Many may point out the difference in the northern and southern kutapas (instrumental ensembles), but Bharata muni himself commented on the matter:

“pravritti or regional identity is recognised through costume, dialect, habit, tradition, custom and occupation. It must be mentioned that there are innumerable variations in the factors that contribute to and establish regional identities. These in fact vary even within a particular region. However, for the sake of brevity, bharata has classified four regional identities. They are daakshiNaatya, aavanti, ooDhramaagadhi, and paancaalamadhyama. Broadly speaking, the classification made by bharata may be taken to mean the southern, western, eastern and northern regions of India, taken in order. each of these regions consists of different tracts of land with separate identities (Ch. XIII).” [2, 57]

Thus, the modern Northern preference for the tabla is immaterial to the overall nature of the common Marga tradition of North and South. In fact, contrary to those cuddly little ‘syncretic’ stories about how the tabla was created by cutting the mrdangam in half, the truth is the tabla was originally called the pushkara drum. Historical evidence can be seen in the ancient temple sculptures at Mukteshwar and Badami.

The mrdangam is also mentioned in the Mahabhasya of Patanjali. It is said that it can be used both as a keeper of tala and as an inspiration to the vocalist. Mrdangam is even referred to as “the supreme percussion instrument”.

Types

Though it is often thought that the dundubhi is the ancient-most of all the percussion instruments, mrdangam has a venerable past in its own right.

Pakhawaj is variant of the older mrdangam. It is said to have derived its named from the sanskrit word Pakshavaadhya, which means side instrument. The Punjabi dhol is related to it.

Interestingly, the etymology regarding the clay origin of the mrdangam is seen in its eastern variant, the khol, which is made out of terracotta.

Finally, there is the Tamizh thavil, which is very enlarged and played with a stick.

Characteristics

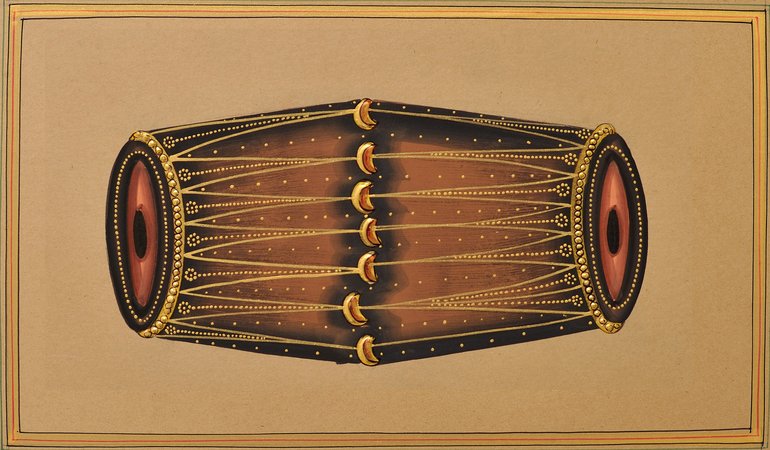

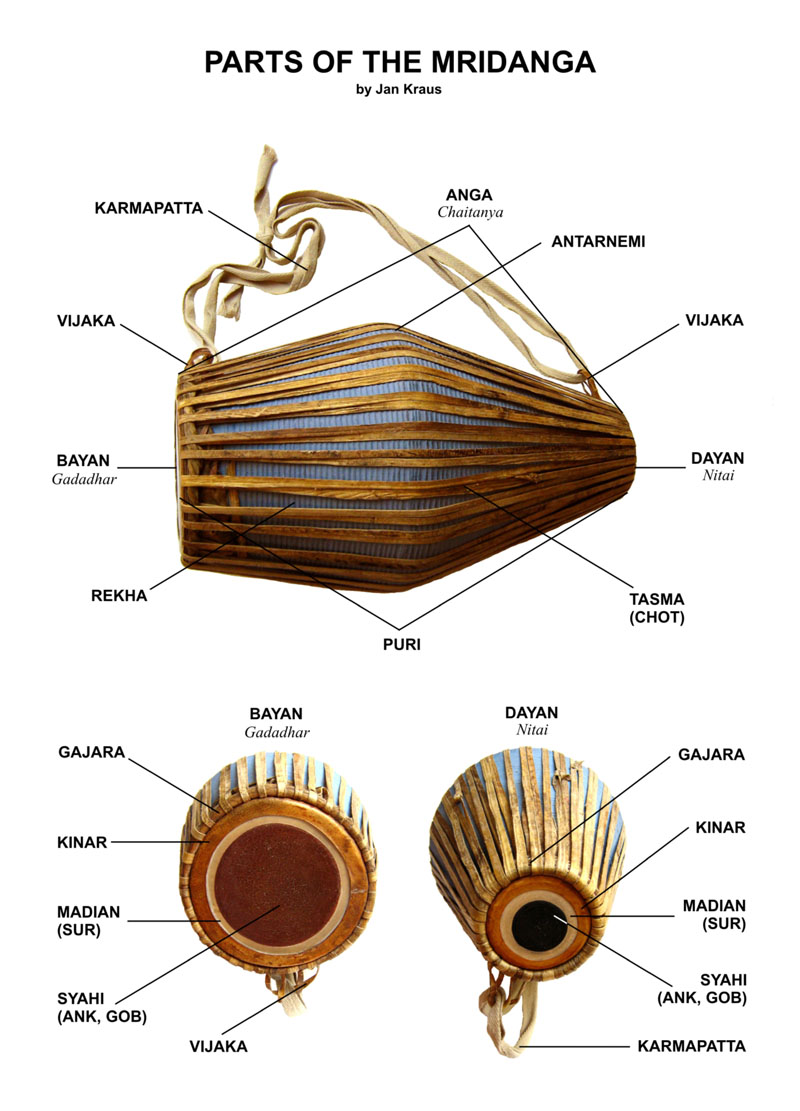

The mrdangam is a barrel drum, unlike the kettle drum dundubhi. It mimics this in appearance. Furthermore, there is generally a larger and smaller aperture to produce a range of sounds:

“The bass aperture is known as the “thoppi” or “eda bhaaga” and the smaller aperture is known as the “valanthalai” or “bala bhaaga”. The smaller membrane, when struck, produces higher pitched sounds with a metallic timbre. The wider aperture produces lower pitched sounds.”

The basic strokes are Tha, Dhi, Ki, Na, Thom:

Process

The process of constructing a mrdangam is one that requires significant time and expenditure. Though jackfruit wood is preferred, morogosa and coconut tree wood are also used. [8]

- The body of the instrument is carved from a single piece of panasa wood

- The diameter of the left head is at least a half an inch greater than the right

- Buffalo leather is used for the outer ring and Goat leather for the inner ring

- A black stone is ground and mixed with powdered rice to make a paste for inner ring

Legacy

“Rhythm (Layam) is the father of music. There is no music, especially Carnatic music without Layam. And, mridangam is the main percussion instrument of Carnatic concerts. It occupies a pre-eminent place in the firmament of global percussion and is rightly known as the “king of percussions.” No other percussion instrument has such unique and varied acoustic properties, structure, tonality and performing capability.” [4]

The antiquity and centrality of the mrdangam to kutapas (ensembles) and vaadhyabrndhas (orchestras) alike cannot be gainsaid. It is the basic instrument of laya and its rhythmic beauty is one that inspires to this day.

The beauty of this instrument is that it can feature as accompaniment or solo performer alike. What matters is the skill of the instrumentalist.

Jaya Senapati states these as qualities for a quality instrumentalist:

“The following are the qualities needed of a Mukhari or an instrumentalist; To be in knowledge of the count of the characters in a rhythmic cycle, to be acquainted with Mayuri, Arthamayuri and Kaarmaaravi, the three Maarjanams or procedures to produce solfa syllables, steady dexterous with the hands, capacity to compose instrumental music, comply with the mood of the character, skill at bringing the group together harmoniously, armed with the skill to entertain, good form, capable of balancing abundance and paucity, in knowledge of the notes of the instruments, genius at composing music, sagacious to hold on and let go at the appropriate time, shrewd to frame patterns in the rhythmic cycles, citra, dhruva, vaartika, and daksina, strong, cautious, well-versed in the progression in tandem with rhythm, physically flawless, acute to cover the dearth of any thing, ingenious at grasping and producing sounds, upright in stance, capacity to play mellifluously, discerning to eulogise the president of the gathering appropriately, the musical notes closely follow him if they are not a part of him, a[n] ear for supporting music, a steady enthusiasm and the hand being perpetually in contact with the instrument.” [3, 437]

Though Lord Vishnu is considered a consummate percussion player, the Puranas also state that Nandi serves as the main mrdangam accompaniment to Lord Shiva, when he dances the Thandava. While it is more difficult to catalogue ancient historical players, here is a listing of mrdangam instrumentalists from recent years.

Famous Players

Hirogi Rao

Palghat Mani Iyer

Palani Subramaniam Pillai

Palghat R.Raghu

Ramanathapuram C. S. Murugabhoopathy

Pudukkottai Dakshinamurthy Pillai

Mavelikkara Velukkutty Nair

Mavelikara Krishnankutty Nair

Sivaraman

T.K.Murthy

Umayalpuram K Sivaraman

T.V.Gopalakrishnan

T S Nandakumar

Karaikudi Mani

Trichy Sankaran

Guruvayur Dorai

Mannargudi Easwaran

Thiruvarur Bakthavathsalam

Arun Prakash

R. Akshay Ram

Nakul Sridhar

Future

Representing Andhra is one of the leading exponents of mrdangam, and a recent recipient of a Padma Sri, Yella Venkateshwara Rao garu. He not only has national recognition, but has the distinct honour of the triple v (vocals, violin, veena) to his name. Despite cultivating these multiple musical talents, mrdangam became his life’s muse.

The Yella International Institute of Mridangam is said to have trained 1500 students under the gurukul system. In fact, many credit him with raising this divine percussion instrument to a purely solo performance level.

So why wait?—start today and learn from modern instructors the basics of this ancient instrument. Whether it is Lord Vishnu or Yella Venkateshwara Rao, the mrdangam is truly the Divine Instrument of Rhythm.

References:

- Iyer, A.S. Panchapakesa.Karnataka Sangeeta Sastra: Theory of Carnatic Music.

- Appa Rao, P.S.R & P. Sri Rama Sastry. A Monography on Bharata’s Natya Sastra. Hyderabad: Natyakala Press. 1967.P.110-112

- Pappu, Venugopala Rao. Nrtta Ratnavali of Jaya Senapati. Kakatiya Heritage Trust. 2013.

- ‘All about Mrdangam’. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-features/tp-bookreview/All-about-mridangam/article15410528.ece

- ‘Treatise on Music’. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/br/2002/08/20/stories/2002082000060302.htm

- ‘Mridangam as the supreme percussion instrument’ https://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-features/tp-fridayreview/mridangam-as-the-supreme-percussion-instrument/article3216709.ece

- Stone, Ruth M. The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Routledge. 2017

- ‘Making of Mridangam’. D’Source. http://www.dsource.in/resource/making-mridangam-instrument-bengaluru-karnataka/making-process