As simple as it is sonorous and as unique as it is universal, this next instrument is a fixture at Carnatic performances. Indeed, it is something that can be found in every traditional and provincial Indian household, and yet, holds a mystique for even the most urbane.

Concluding our Series on Carnatic Classical Instruments is the last of the major native contributions to the modern Kutapa: Ghatam.

Introduction

As stated previously, the Musical instrument (Aathodhya or Vaadhya) [2,110] in our Classical Indic Music is of four kinds: Thatha vaadhyam, Sushira vaadhyam, Avanatta vaadhyam, and Ghana vaadhyam. “They are respectively called stringed instruments, thulai (hole) instruments, leather instruments and metal instruments.”[1, 97]

In tandem with the categories stated above are a horizontal set of divisions. These are Sruthi, Sangeetha, and Laya

“Sruthi Instruments: Ta[m]bura (Thatha) – Otthu (Sushira), Sruthi box (Sushira).

Sangeetha Instruments: Veena (Thatha), Gottu (Thatha), Violin (Thatha), Flute (Sushira), Nagaswaram (Sushira), Harmonium (Sushira), Jalatarangam *Water is poured in [por]celain cups and then played by sticks).

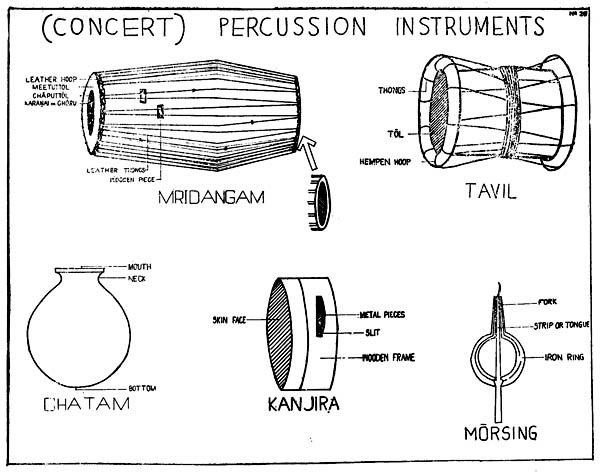

Laya Instruments: Mridangam (Avanatta), Thavul (Avanatta), Keethu (Thatha), Moorsing (Gana), Kanjira (Avanatta), Ghatam (Mud pot), Jalar (Gana)-Bronze).” [1, 97]

Arguably the only outlier is the Ghatam, which is a percussion instrument. In light of that, a better series of equivalents has also been proposed by others. That is, chordophones (thatha), aerophones (sushira), membranophones (avanatha), and ideophones (ghana). Ideophones are any solid instrument, without leather coverings or other membranes. The clay ghatam (originating from the sanskrit ghata), would therefore be correctly classified under ghana vaadhya. Non-classical instruments which have now become part of the modern Carnatic repertoire are the western imports such as Violin, Harmonium, and Sruthi Box (alternately known as electronic Tambura).

Idiophones are generally of 3 types: clashed, struck, and shaken. Some also give the meta-divisions of striking and plucking. [3, 37] Of all the ghana vaadhyas, the ghatam is the most unassuming. Ostensibly accessible to all, it truly shines in the hands of maestro.

“the ghatam is classified as an upapakkavadya (an accompanying instrument that is secondary to mridangam)” [4]

History

Pot instruments have their own sub-category of bhanda vaadhya. This is because they are barrel type devices that are moulded to bear weight or in many cases water. Due to their modest appearance, they are often thought to be among the oldest of aathodyas.

“In ancient literature, Ramayana and Jatakas, etc., we get references of bhanda vadyas in abundance which were of various shapes and sizes. We get the details of the earliest pot drums in Natya Shastra in which it is called dardur and constitutes an important part of the ensemble along with the mridang and panav. The instrument can be seen in the sculptures of various temples. ” [6]

There are several regional variations. For example, there is the noot of Kashmir, the matki of Rajasthan, as well as the gharha of Punjab. While these are considered to be more for folk performances, there is the rouf, also of Kashmir, which is for connoisseurs of more metropolitan music. Like the ghatam, these are made of burnt clay. There is also the gagri/gagra of the North Indian plains, but this is typically made of brass or copper. [3, 46]

“The first man who developed the instrument as an [Carnatic] accompaniment was probably Vidwan Chidambara lyer of Polagam. He flourished in the latter half of the nineteenth century.” [6]

Characteristics

Much like the sanskritic kumbha (pot) from which it takes its form, the ghatam is made of clay.

“The body of the instrument is struck at various places with fingers and palms, but never on its mouth. The player also presses the mouth of the ghatam onto his abdomen to various degrees, producing fine tonal diffe-rences. In the hands of an accomplished musician this innocuous pot can become a beautiful rhythmic accompaniment.” [3, 46]

For convenience and longevity of the instrument, the ghatam is typically placed on a ring of cloth. This also permits it to resonate without interference.

A musical matriarch of Manamadurai named Meenakshi Ammal was the famed purveyor of ghatams to all the marquee musicians. She won the Sangeet Natak Award in 2013 for instrument manufacture. As this article discusses, “All ghatam players have bought the instrument from Meenakshi Ammal, whose family has been making the ghatam for over four generations. A winner of the President’s award in 2014, she is survived by her son Ramesh, who is also a ghatam maker.” [5]

Nevertheless, there are makers of this musical clay pot throughout India, and these artisans should all be given patronage. While it is prima facia a plain object to make, this characterisation of the ghatam’s manufacture is deceptively simple. “Ghatams are made of clay with iron fillings. Copper, silver, gold and aluminium particles are also mixed with the clay to give the instrument sweet and resonant tonal quality.” [6]”A mixture of four types of sands is used for making ghatam. Graphite and senthuram are also mixed with the clay to add strength. ” [5]

“The south Indian ghatam has become a highly sophisticated instrument, raised to a concert status. The clay chosen for making the pitcher is of a special type and the instrument itself has to be carefully shaped and fired in the kiln. Besides its superior quality as compared to the noot, the mode of playing is also very different.” [3, 46]

The vattam (ring) is used to provide a sturdy platform from which to play. It is typically made of straw and wrapped with cloth.

Legacy

“The ghatam is an instrument born from the elements and pure in its essence. It is made from the earth, forged in the fires, rested in the shadows of the sun and contains the air and sky. It boasts of no pretensions but it will sing only when in the right hands” [5]

The Legacy of the ghatam is of long-lasting and of immediate import. It is not enough to merely pay lip service to musical patronage, but for cultural doyens to ensure even instruments and instrumentalists sidelined from spotlight get the support they deserve.

Oft-ignored due to the primacy of the mrdangam, the virtuosity of the karathaala, and the facility of the kanjeera, the ghatam has a unique place among percussion instruments. Ghana and Avanatha vaadhyas provide both the beat and rhythm of the night during marghazhi season kutcheris as well as casual kutapas.

Many vaadhyakaras have made their mark, and recognition of their contributions ensures the next generation will be interested to take up more constructive hobbies.

Famous Players

Thetakudi Harihara Subash Chandran

Thetakudi Harihara “Vikku” Vinayakram

Srishyla

Kottayam Unnikrishnan

Abhay Vikranth

Giridhar Udupa

Ghatam Suresh Vaidhyanathan

The Ghatam may comparatively be of more humble extraction, yet its role in making Saastriya Sangeeta more reachable to the rasika and non-rasika alike cannot be gainsaid. Rather than all parents corraling their kids into the same carnatic endeavours, perhaps it’s time to identify the child’s talent and to urge them accordingly.

The ghatam can be easily learned through professional classes or online instruction. All that is required is interest, an instrument, and the will to see the training through.

References:

- Iyer, A.S. Panchapakesa. Karnataka Sangeeta Sastra: Theory of Carnatic Music. Chennai: Ganamrutha Prachuram.2008

- Bai, Kusuma K. Music-Dance and Musical Instruments: During the Period of Nayakas (1673-1732). Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrit Bhawan. 1999

- Deva, B. Chaitanya. Musical Instruments of India: Their History and Development. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publ. 2014

- “Sukanya Ramgopal’s lone battle to play the Ghatam”. The Hindu. (December 30, 2017). https://www.thehindu.com/entertainment/music/sukanya-ramgopal-has-been-fighting-a-lone-battle-to-play-the-ghatam/article22324959.ece

- “The Pot on the Stage”. The Hindu Businessline. (May 9, 2014). https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/blink/watch/The-pot-on-the-stage/article20852782.ece

- “Ghatam”. India Instruments. https://www.india-instruments.com/encyclopedia-ghatam.html