Following our previous article on the Karathaala, the next instrument provides a knotty little conundrum tied by the naughty.

One of the prime drivers behind this Continuing Series on Carnatic Classical Instruments is reviewing the origin and development of Classical Indic Music and Instruments through indigenous eyes. Motivated musicologists have long attributed our musical instruments and even music itself to foreign importation. The next Instrument is no exception, and is properly called Tambura.

Introduction

“As used in India, plucked instruments can be divided into two broad classes: the non-melodic and the melodic. The former in-cludes chordophones which are only drones and rhythm keepers; the second group comprises all those on which melodies can and are produced.” [1, 129]

The Tambura is first and foremost a drone instrument. In Saastriya Sangeeta, it would be classified as a Sruthi Vaadhya. Pronounced thamboora, it is sometimes stated to have been derived from the ekatantri (single stringed veena). Similar devices such as Gopi Yantras and ananda laharis are used throughout eastern India, particularly by Vaishnavite bauls (wandering minstrels). [1, 129]

“A further stage in the construction of the drone is found in the tamboori of Andhra and Mysore; in the latter region it is also called the chikka veena. (Rajasthan has similarly the chau tar.)” [1, 130]

As stated previously, the Musical instrument (Aathodhya or Vaadhya) [5,110] in our Classical Indic Music is of four kinds: Thatha vaadhyam, Sushira vaadhyam, Avanatta vaadhyam, and Ghana vaadhyam. “They are respectively called stringed instruments, thulai (hole) instruments, leather instruments and metal instruments.”[4, 97]

However, there is a more recent and more precise characterisation of these divisions. They are as follows: Chordophones (string), Aerophones (wind), Membranophones (covered), and Idiophones (metal/wood). [1, 3]

History

Erroneously called ‘tanpura’ by persianised parvenus, the Tambura is an august Indian instrument of great antiquity. In fact, tanpura/tanbur is a middle eastern corruption of the chaste Sanskrit Thamboora. This is seen in balkan countries where the full word is essentially retained through alternate spellings such as tambouras, tambourica, even tambura in the Balkans. In fact, the foreign and foreign influenced themselves attest to this. “Some scholars are of the opinion that the ravanahasta veena or ravnahatta of western India migrated to Western asia to become the rabonostron, the rebec, the rabeb and finally the violin…

Erroneously called ‘tanpura’ by persianised parvenus, the Tambura is an august Indian instrument of great antiquity. In fact, tanpura/tanbur is a middle eastern corruption of the chaste Sanskrit Thamboora. This is seen in balkan countries where the full word is essentially retained through alternate spellings such as tambouras, tambourica, even tambura in the Balkans. In fact, the foreign and foreign influenced themselves attest to this. “Some scholars are of the opinion that the ravanahasta veena or ravnahatta of western India migrated to Western asia to become the rabonostron, the rebec, the rabeb and finally the violin…

Abdul Razak Kanpuri is of the opinion that the original word is Indian Tamboora which gets modified to tunbura in Iran and Arabia. This would mean that the whole set of lutes in the West owe their birth to Indian sources.” [1, 25]

This is further underscored by the Tamburi instrument used in rural Andhra. Finally, Tamboora also finds an associate noun in Sage Tamburu, famous for his skill in musical instruments. The celestial being from the legendary kinnara race is considered rival to Narada Muni himself.

As for the etymology, the name itself derives from the word tumba (meaning large gourd) which is used for the resonating bowl. [1, 131] Therefore, “Tamboora being an instrument from the Middle East is doubtful.” [1, 133]

Types

“The concert tamboora, both in the South and in the North (where it is known also as the tanpoora) is only a sophisticated version of this rural instrument”. [1, 131]

Rather than the tambura being an importation from outside India, it may very well be an evolution from the tamburi from within rural India.

“Sangeeta Parijata of Pratapa Singh Dev gives two types of tumboora (ch.2 on musical instruments) anibaddha and nibaddha, i.e. unfretted and fretted. The former one was also called the tamboora.” [1, 134] The southern variety (the best known of which is the Thanjavur) is typically smaller. The northern meeraj has a gourd of 70-90 cm in girth and a height of 105-120 cm. The broader version is referred to as the male tambura, and the more svelte is considered the female.

There are typically two ways to hold it. The first is the urdhva, where it is held upright. The other is horizontally across the lap.

Characteristics

“The Tambura which gives the sa-pa-sa Sruti notes is pure therapy to the mind and soul. Sit in a quiet place with eyes closed and listen to the notes of a perfectly tuned Tambura — the effect is therapeutic.” [3]

Drone instruments are known for setting the sruti (pitch). This background provides a base through which interaction via vocal or other instrumental gives harmony.

“In the modern time, the method of tuning is gene-rally worked out by the method of tempering two of the strings of the tambura, in mostly the tones, shadja and panchama or shadja and madhyama. The shadja being the drone or tonic” [7, 133]

A bowl-shaped resonator converges into a neck and an hollow fingerboard. The tuning is typically Pa1, Sa, Sa, & Sa1. [1, 130] Strings of brass and steel are typically used. The most prominent Indian aspect, further lending credence to indigenous origin, is the bridge.

“C.V.Raman had earlier shown that it was the slope of the bridge which was the cause of the beautiful tone of the instrument.” [1, 131]

Process

As the theory goes, “the placement of the fine thread of cotton, silk or wool under each string, on the bridge, was even more important than the grazing contact of the string with the bridge, as it is the reason for the fine tonal modulation and the rich sound of the tamboora“. [1, 131]

In the case of the tambura, it is typically carved from a single piece of wood from which the instrument is scooped. Coming from the lute family, strings are essential and are tied after the wood is lacquered. However, the most distinguishing feature is one for which it is not quite well known: the bridge.

“Indeed, the wide bridge and jeeva (jeevali) thread are amongst the most creative contributions of India to world instrumentation.” [1, 132]

Legacy

“The more sophisticated a society, the more specialized its various activities tend to become. Music, which is always associated with dance, rituals and festivals, becomes ‘pure’ music with us.” [1, 113]

The legacy of the Tambura is as much the story of world music as it is Indian music. Variations of this queen of pitch can be found both in the middle east and west. So widespread has its impact been, and so singularly consistent is its name, that the tambura has become yet another battleground for musical credit. However, the Indian case for its origin is not only on solid ground, but trenchantly marked by musicological and mythological origins.

“The ekatantri was a long bamboo tube on which was tied a single string, and hence the name. It had a single gourd resonator. The bridge seems to have been wide and here we meet the early use of jeeva, so common in the modern tamboora. ” [1, 136]

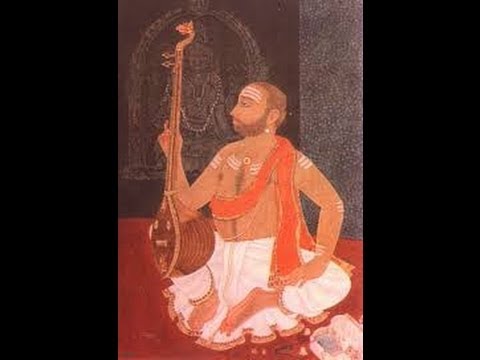

Famous Players

Despite not being a solo instrument, and possessing minimal patronage, a number of dedicated musicians have dedicated their lives to it.

V. Jagannatha Rao

Sripada Rao

Hulikal Prasad

Jayant Naidu

Though an Andhra man, Mumbai raised Jayant Naidu was schooled in Hindustani. He has become an expert player of the Tambura, and has accompanied all the majors vocalists in that tradition.

Prakash Naik

Future

“Tambura-playing and tuning is an evolved and high-class art. The slightest disturbance in sruti will disturb the performer and reflect on the concert.” [3]

The future of the Tambura is simultaneously both bleak and bright. On the one hand, electronic apps and sruthi boxes have almost completely replaced it, and on the other, a dialogue has begun regarding the instrumentality of this instrument. Carnatic Sabhas have a key role to play, not only in stocking tamburas in their halls, but crediting tambura players in their programmes and giving decent remuneration.

Moreover, the Malladi brothers, students of Nedunuri Krishnamurthy, are known for their training students in it. Other teachers insist on as many as 15 months of training in tuning a Tambura before commencing any other musical instruction. [3] Such is the importance of sruthi, and the tambura is its conductor. It is the provider of naada, such is the essence of this instrument.

“The word ‘Nada’, though represents a mere sound, will only denote a musical sound. Nada is the life and soul of the art of music.” [2, 3]

References:

- Chaitanya Deva, B. Musical Instruments of India: Their History and Development. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. 2014

- Leela, S.V. Indian Music Series: Book I. Madras: Minerva Publishing House. 1980

- “Tambura on the Brink”. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/entertainment/music/tambura-on-the-brink/article23382822.ece

- Iyer, A.S. Panchapakesa.Karnataka Sangeeta Sastra: Theory of Carnatic Music. Chennai: Ganamruta Prachuram. 2008

- Appa Rao, P.S.R & P. Sri Rama Sastry. A Monography on Bharata’s Natya Sastra. Hyderabad: Natyakala Press. 1967.P.110-112

- The Tanpura players. Mumbai Mirror. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/opinion/columnists/sumana-ramanan/the-tanpura-players/articleshow/52514797.cms

- Prajnananda, Swami. A History of Indian Music (Vol.I). Kolkata: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math. 1997