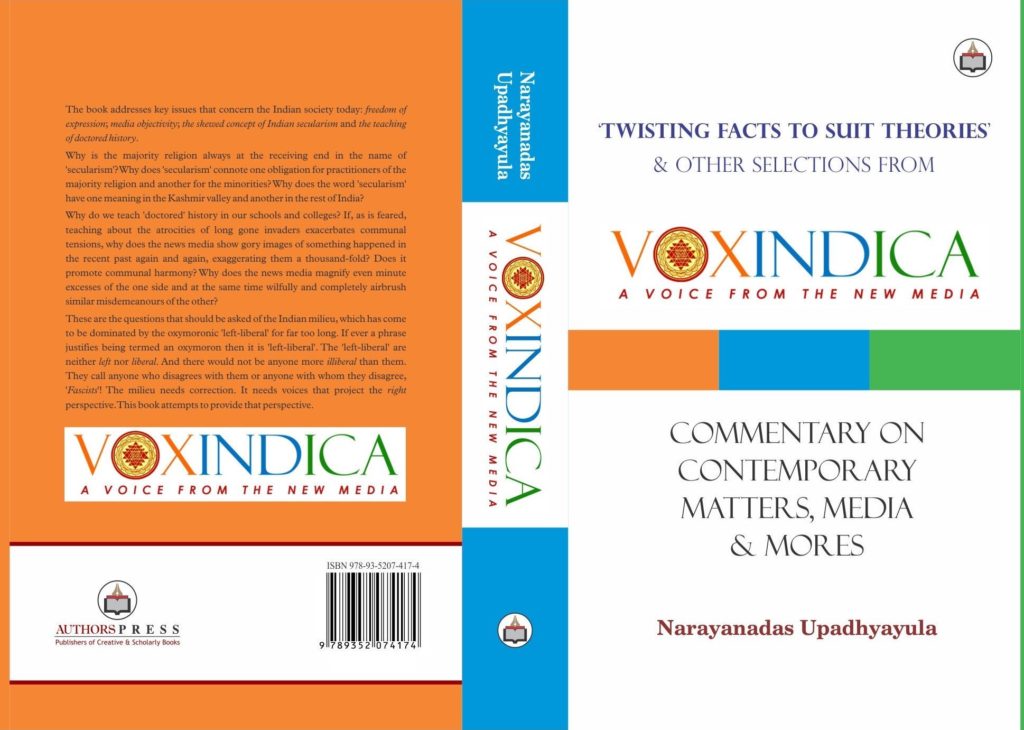

Amidst a panoply of articles and books in the cacophony of conservative Indian thought, there occasionally comes a simultaneously erudite yet lucid commentary on the body politic. Narayanadas Upadhyayula gaaru is one such voice. He has spoken up on a much needed topic for India in general and Andhra in particular.

At a time when Andhra Pradesh state has been divided into two, and what remains of the state is divided by caste, he is one voice who has called for healing the lines of division through proper education. Here is his own account of the state of affairs in the Indian political dialogue, and why a more cultured and clear-headed approach is required to take on the issues of state, especially in a state riven by factionalism.

From the travails and tribulations of the Kashmiri Pandits to the elusive Bharat Ratna to Telangana’s P.V. Narasimha Rao, numerous controversial issues are deftly dealt with.

From 1947’s Integration of India to the 2008 Nuclear Deal, Narayanadas gaaru covers it all, beginning with principles and juxtaposing them with implementation. Fact and fiction are teased apart with clinical precision.

He asks key questions, but is also the rare Vox Indica for the common Bharatiya who not only gives answers but evaluates workable solutions as well. The book is a breath of fresh air. While most members of the chatterati alternate between cultural marxism and jingoism, he provides the sober-headed analysis of a true desa-bhakta. From a lineage of traditional Telugu scholars, Narayanadas Upadhyayula is himself a prolific writer, recognised in India for his wide-ranging web log commentary. As for the book, his first, here he is in his own words:

“The book addresses key issues that concern the Indian society today: freedom of expression; media objectivity; the skewed concept of Indian secularism and the teaching of doctored history.

Why is the majority religion always at the receiving end in the name of ‘secularism’? Why does ‘secularism’ connote one obligation for practitioners of the majority religion and another for the minorities? Why does the word ‘secularism’ have one meaning in the Kashmir valley and another in the rest of India?

Why do we teach ‘doctored’ history in our schools and colleges? If, as is feared, teaching about the atrocities of long gone invaders exacerbates communal tensions, why does the news media show gory images of something happened in the recent past again and again, exaggerating them a thousand-fold? Does it promote communal harmony? Why does the news media magnify even minute excesses of the one side and at the same time wilfully and completely airbrush similar misdemeanours of the other? “

AVAILABLE THROUGH AMAZON ONLINE STORES:

………………………………………………………….

LINK FOR ORDERING YOUR COPY FROM INDIA:

https://goo.gl/FWtTsJ

LINK FOR ORDERING YOUR COPY FROM OUTSIDE INDIA:

https://goo.gl/s4FXGm

ORDER YOUR COPY NOW!

[Below is an Excerpt from the featured book Vox Indica]

______________________________________________________________________

Learning or Political Conditioning?

If we are asked to name a singular, monumental failure of independent India, we can unhesitatingly point out that it was our inability to forge a national spirit. Every institution contributed to this failure including the education system. This essay excerpted from ‘TWISTING FACTS TO SUIT THEORIES’ AND OTHER SELECTIONS FROM VOXINIDCA’ (pp. 290-298) examines the role played by text books written for school students and how they contributed to exacerbate rather than reduce caste schism. In particular it critiques the Class IX social science text book published by NCERT in 2007.

In common understanding, learning means the acquisition of knowledge and skills. In terms of behavioural sciences learning implies acquisition of knowledge, skills and attitude resulting in permanent change in behaviour. It is attitude that informs thought processes and character. This is the reason why traditional Bharatiya education focused on shaping attitude and character. Behaviour has two other modifiers: experience and conditioning. Experience is gained by repeated application of knowledge and skills. Conditioning is the result of positive or negative experiences. Conditioning is the rationale underlying the ‘carrot and stick’ principle of motivation. However, hardened attitude can sometimes override knowledge and skills in shaping behaviour. For example, erudition may not bar a university professor from becoming a criminal; or a well-educated highly-paid individual from becoming a terrorist. The focus of traditional Bharatiya education on behaviour and character was to defy experiential conditioning. It was to tread the path of righteousness irrespective of positive or negative experiences.

The three dimensions of learning are: education which helps in the acquisition of knowledge; training which helps in the acquisition of skills and development which implies positive modification of behaviour of a permanent nature. Competence is the ability to selectively apply knowledge, skills and behaviour to suit the context, to achieve desired results or performance. The objective of learning that we impart in schools and colleges is to inculcate all three. Viewed in the light of this preamble, how do the NCERT textbooks shape thought, attitude, character and behaviour? The NCERT Social Science textbook for Class IX, published in 2007, is rather grandiosely introduced to the reader:

“All too often in the past, the history of the modern world was associated with the history of the west. It was as if change and progress happened only in the west. As if the histories of other countries were frozen in time, they were motionless and static. People in the west were seen as enterprising, innovative, scientific, industrious, efficient and willing to change. People in the east—or in Africa and South America—were considered traditional, lazy, superstitious, and resistant to change.”[1]

After reading this, the reader is likely to be confused by the introductory part of ‘Section I’, as it interprets the ideas that shaped India’s freedom movement. The latter informs the reader that ideas like liberty and equality, products of the French Revolution and socialism, product of the Russian Revolution, have informed anti-colonial movements in India and China. It mirrors the Western view that Gandhi was inspired by Rousseau, the French Revolution and Thoreau.

The chapter on ‘Socialism in Europe and the Russian Revolution’ (p. 25-48), written by Prof. Hari Vasudevan of the Calcutta University, describes the origins of the Russian Revolution in glowing terms:

“The political trends were signs of a new time. It was a time of profound social and economic changes. It was a time when new cities came up and new industrialised regions developed, railways expanded and the Industrial Revolution occurred.” (p. 26)

To say that the chapter is economical with the truth would be an understatement, as what it does not mention about the Russian Revolution is perhaps at least as important as what it does. For example it bypasses the more fundamental question that strikes anyone interested in the history of Communism: “Why did a doctrine premised on proletarian revolution in industrial societies come to power only in predominantly agrarian ones, by Marxist definition those least prepared for ‘socialism’?”[2]

Nor does it mention that “Communism’s recourse to ‘permanent civil war’ rested on the ‘scientific’ Marxist belief in class struggle as the ‘violent midwife of history’, in Marx’s famous metaphor”. (Ibid. p. xix)

The one party rule which suppressed democratic rights, the reprisals, the forced labour camps, the executions all get passing mention as if they were minor, insignificant details. The chapter mentions the severe reprisals, deportations and exiles meted out to those who were opposed to Stalin’s collectivization programme. But there is no mention of the suppression of the right to free speech, an issue so dear to the ever-agitating Indian communists. There is also no mention that an estimated 100 million lives were sacrificed at the altar of the ‘class struggle that was the violent midwife of history’, the world over, and about 20 million deaths in the erstwhile Soviet Union alone. The Chinese version of Marxist Communism, to which a majority of Indian communists owe allegiance, consumed a staggering 65 million lives in its class struggles. (Ibid. p. 4)

The introductory part of ‘Section I mentions in passing that ‘[t]oday Soviet Union has broken up and socialism is in crisis …’ But the chapter on Russian Revolution was not revised to reflect these changes in the 2007 edition, brought out a good sixteen years after the implosion of the Soviet Union and the larger Communist world. The following passage almost gives the impression that socialism (or Communism) continues to rule about half of the world, as it did earlier and that the USSR is alive and kicking:

“By the end of the twentieth century, the international reputation of the USSR as a socialist country had declined though it was recognised that socialist ideals still enjoyed respect among its people. But in each country the ideas of socialism were rethought in a variety of different ways.”

Is there a deliberate attempt to downplay the excesses of the Moguls and the Communists, and the decline of Communism on the one hand and magnify social distinctions in the Hindu society on the other?

Click here to Buy this Book!!!