To understand Dharma is to understand Indic civilization and the Andhra culture.

It is Dharma that is the organizing principle of Bharatavarsha (India) and indeed, the most powerful idea in the literary heritage of India in general, and Andhra in particular.

Thus to understand and appreciate the culture of the Andhras, one must be conversant in the ways of Dharma. This section will concentrate on articles and specific literary passages that highlight the subtlety, context sensitivity, and profoundness of Dharma in Andhra and beyond.

Personalities

Apastamba

Nimbarka

Vidyaranya

Satya Sai Baba

Articles

Purusharthas

- Dharma

- Artha

- Kama

- Moksha

On the Kaula doctrine (misnomer: tantra)

On Sampradayas

On Varnashrama Dharma

Cleanliness is Next to Godliness

The Ramayana

The Mahabharata

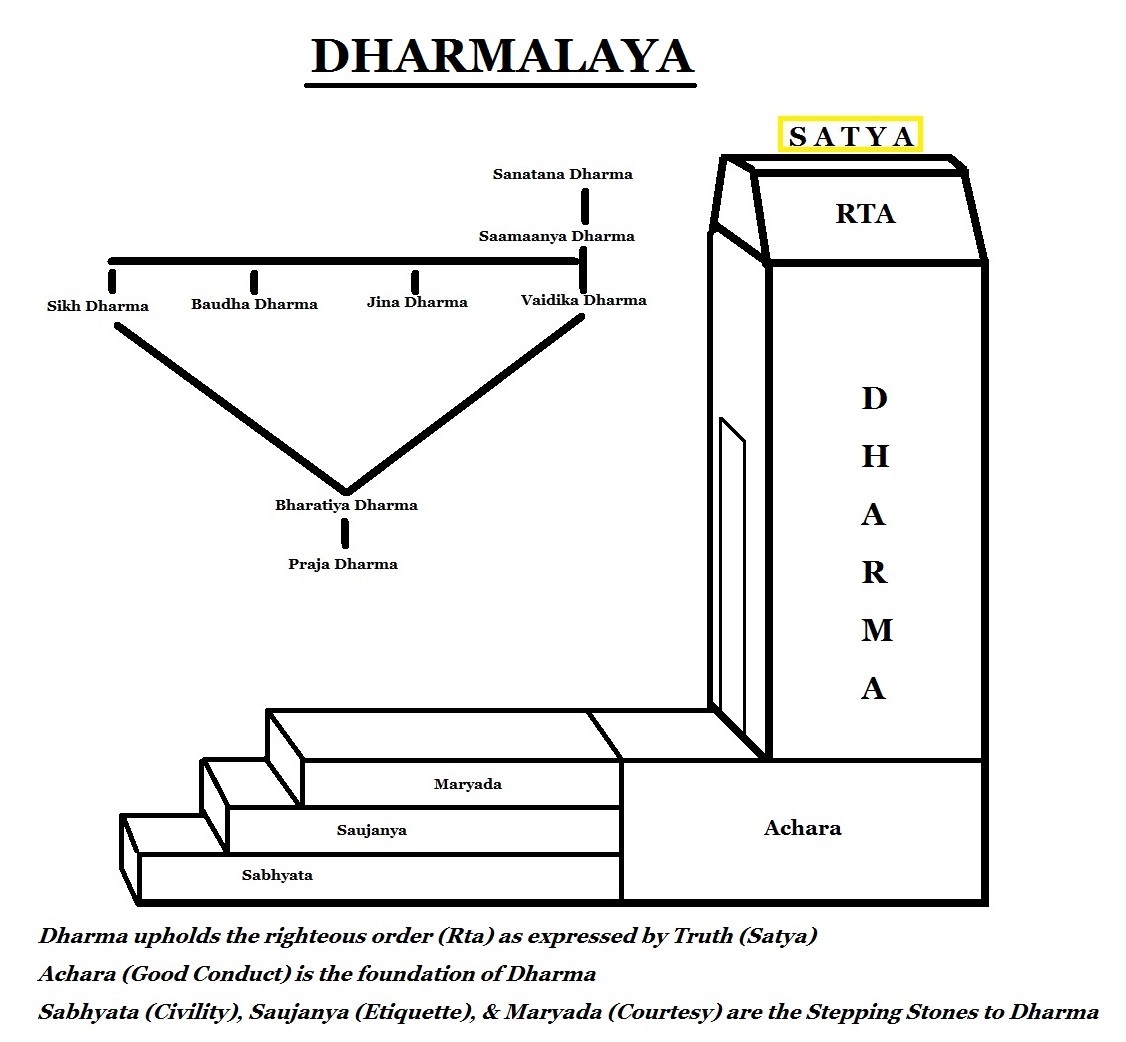

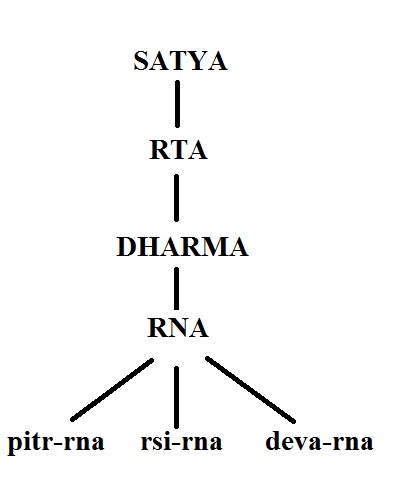

On Dharma

The essence of Dharma is not based on an obsession with caste or ritual. Rather, it is about righteousness and duty and sacrificing one’s self for others. To understand dharma is to understand the cosmic order of the universe, Rta, which is rooted in truth, Satya. Dharma’s root word in Sanskrit is dharyate (literally, to uphold the order). Thus, practitioners of dharma must uphold this order.

The core of this order is not focused on the trivialities of caste and the divinely intended accident of birth, but rather, of mother raising child, husband protecting wife, child taking care of old parents, and rich assisting poor. It is about strong defending weak and putting societal interest before self interest–that is the heart of Dharma.

Vaidika Dharma (sanatana dharma as expressed by the Vedas) has three parts, karma kanda (which requires ritual and yagna), jnana kanda (knowledge of the truth as contained in the Upanishads), and upasana/bhakti kanda (which emphasizes compassion for all and devotion to God as seen in the Bhagavata Purana).

Karma kanda is the spiritual kindergarten (Swami Vivekananda himself spoke of this). It disciplines the individual so that he is fit to receive knowledge of reality (jnana). This knowledge and awareness of God, or Brahman, in all things, is what leads to worship/devotion and compassion (upasana/bhakti and karuna) It is for this reason that Vedanta, literally the End of the Vedas, is the object, rather than mere yagna and ritual.

Those who misunderstand or even misinterpret dharma get lost in the trivialities of karma kanda. They grow arrogant of their religious merit and birth and forget the true purpose of the exercise. If we are all mere creations of God, where is the place for arrogance and contempt towards our fellow man of whatever background? After all, could not the brahmin have been a dalit in a previous life? Could not the dalit have been a brahmin in a previous life?

Arrogance of birth, lineage, caste, knowledge, and religious merit are some of the most dangerous as they lead away from the path of sanatana dharma to false ego, pride, anger, and destruction. Mere puja and archana doesn’t take us to God; they are but a start and also an aid to the troubled and anxious. Dharma is the path, and it is acted in the outside world. How we conduct ourselves in all settings (not just in the puja room) and how we treat others is how we are ultimately judged for fitness to reach God.

Vaidika dharma does stipulate varnashrama dharma. Literally this emphasizes the division of labor (varna–caste is a misnomer) and stage of life (ashrama) as stipulating the right course of action in a given context. The logic behind this is that no member of society will simultaneously have spiritual, politico-military, commercial, and labor power simultaneous. Any concentration of power with 2 or more of these types of power leads to tyranny, oppression, and adharma.

While historically traditions naturally passed from father to son (even outside India), in our era, people foolishly believe that birth itself grants privilege. What people forget is that with privilege comes duty.

As such, it is conduct that is the key determinant of a person’s true varna. The dharma or duty that one chooses to follow, whether as teacher/spiritual guide, administrator/warrior, merchant/farmer, or artisan/worker must not be cause for arrogance, but cause for humility. With each varna dharma comes a responsibility to society.

Each individual, no matter how privileged his birth, has a solemn and inalienable duty to society, and should not only behave in harmony with his chosen varna dharma, but must behave in line with the moral commands of Sanatana Dharma, the Eternal Dharma, which is the origin of all dharmas. Each varna is but a mere spoke in the wheel of society, and it is the Chakravartin who turns the wheel in order to uphold Dharma under the auspices of God. Thus those who become arrogant should remember that God has the ability to both grant and take away their position, and they must not abuse their power. Stewardship must be the mindset. Kings do not rule for only their pleasure and glory, and brahmins do not conduct yagnas for their own privilege; both operate as stewards ruling and teaching respectively while being ultimately accountable to God.

To move Dharma forward into the modern era, the mistakes of the past must be rectified. This means that the dalit communities of Andhra have to be fully integrated. As is the law of the land, so to must untouchability be eliminated at the social level. After all, if the original thinking behind the system was that those who transgressed Dharma would be ostracized from society, how can upper and middle castes continue to bar dalits if they don’t outcaste their own caste brothers who eat beef, etc. today? People cannot ask for privilege while failing to do their duty. What kind of system gives only rights without responsibility?This is certainly not Varnashrama Dharma, let alone Sanatana Dharma.

According to the dharma sutras themselves, outcasted members of society or their descendants can be readmitted after prayascitta (penance/observance) and shuddhi. It is possible to do this by properly and sincerely readmitting Andhra dalit jatis back into religious society. This is the best means of not only ensuring social justice to a wronged community, but of ensuring Dharma itself.

Accordingly, there have been many misinterpretations of dharma along the way. One such example is the treatment of the leather worker. While it is one thing to outcaste brahmins, kshatriyas, vaishyas, and sudras who commit personal sin, it is another to unfairly outcaste entire jatis of honest workers performing a service that all of society requires. If leatherworking itself is sin, then let all those who wear leather be outcasted as well. People cannot have their cake and eat it too. Leather working is honest work as is sanitation and all members of Andhra society must be integrated. Certainly, God himself will not enter, let alone bless the entrants and employees of, a temple that bars his devotees from entering.

Ultimately, what must be remembered by the more ritually inclined of whatever varna is that karmakanda is merely the kindergarten. It is the starting point so that people are fit to receive true knowledge of the existence of God in all things and all living creatures, and most importantly, all human beings. While one can read to know, reading is not understanding. So whatever are the requirements of ritual, be kind and courteous in the performance of those duties, for one will find that jnana and upasana kanda will lead to understanding why humility and compassion for all living things are the gunas that God ultimately wishes to encourage.

Think of others before you think of yourself, that is the surest path to God and at the heart of Dharma.

On Acara

In the Vishnu Sahasranama, it is stated that “Acara leads to Dharma, and Dharma is the path to Krishna”. As such, individuals must first master good conduct as the stepping stone to understanding and embodying righteousness.

In the Vishnu Sahasranama, it is stated that “Acara leads to Dharma, and Dharma is the path to Krishna”. As such, individuals must first master good conduct as the stepping stone to understanding and embodying righteousness.

Of late, there has been some misunderstanding about Acara. The Manusmriti is often selectively cited to emphasize that Acara is somehow the highest Dharma coming before anything and everything—but such people represent a flawed understanding. They hide behind this to justify their emphasis of kalpya or ritual aspects of Acara, as though Purva Mimamsa were the only and highest darsana (philosophical view). But this is not the case, and it is certainly not Vedanta, which the Gita embodies.

Acara is not the highest dharma—how could it be? Was it Acaram for Yudhisthira to say “Ashvathama attaha…kunjaraha”? Was it Acaram for Bharata to angrily scold his mother for her conspiracy against Rama and disown her? Was it Acaram for Dhristadyumna to kill a learned Brahmin like Drona?

No, of course it wasn’t—but it was Dharmam, because all these actions were intended to ensure that Dharma and Rta (the cosmic/just order) were protected. Krishna made Yudhisthira speak a lie because Drona could not be defeated in battle and had to be removed to ensure the victory of the righteous Pandavas over the evil Kauravas. Bharata had to scold his mother and even disobey and disown her so she would come to her senses for the sin she had committed by overturning Rama’s birthright as firstborn heir to the throne. It was appropriate for Dhristadyumna to kill Drona, because Drona had taken up arms and sided with Adharma, thus neither his status as a learned brahmin nor his identity as beloved guru of Arjuna could be allowed to protect him from the consequences of his actions. Thus in all these cases, Acara was broken, but Dharma was protected.

What then is the highest dharma, you ask?—Sacrifice.

No, not Yajna (that’s a different type of sacrifice)—but Tyaga (which is self-sacrifice).

Don’t get me wrong. Acara is very important. In fact, it is the building block of Dharma. The foundation that allows individuals to grow ethically and then morally, and allows societies to have a stable and just order. But Acara has, all too often, been an excuse for some sections to get lost in mindless ritual. Ritual without reflection is mere robotics.

Sri Ramana Maharshi asked of what use it was to be a lettered man if it means merely becoming a gramophone—mindlessly and brainlessly chanting mantras and performing yajnas without improving himself. Developing Atma-vichara (self-reflection) and Viveka (ability to discriminate between right and wrong) is thus the critical first step to liberation from samsara.

Thus, while varnashrama dharma historically has had a place in guiding one’s duty to society, Sanatana dharma at its highest levels is about the essentials of morality. These are the divine qualities, or gunas, of Pavitrata (purity), Karuna (compassion), Saamyama (self-control ), Yuktata (justice), Satya (truth), Tyaga (self-sacrifice) and above of all Bhakti/Prema (Divine love). This Prema is what makes possible love for the rest of society and willingness to engage in Tyag to safeguard it. This is because if the Tyagi is willing to sacrifice even himself for a greater cause, then he is willing to restrain his pleasures to avoid hurting others.

This self-sacrifice is not the mindless behavior of lemmings—giving themselves up for the slightest cause (or as masquerade for atma-hatya)—but rather a studied, difficult, and frequently reluctant one. This is because it weighs the interests of the individual against the needs of society. In fact, the most brilliant and insightful dialogue in the arbitration between Rama and Bharata comes from Rajarishi Janaka himself, who says “it is easy to to die, but it is often harder to live for your loved ones”. Thus, it is critical that individuals properly study dharma to understand when the former or latter is more appropriate.

People think that it is great evil that begets the horrors and disasters of the world, but the reality is that it is the little evils, the petty injustices that occur so frequently that aggregate over time and cause destruction.

It is the dismissive cavalier remark that breeds resentment. It is the mean-spirited mockery that builds hatred. It is the thoughtless messiness that causes disgust. Because most people seek to avoid conflict, the frustration that brews from such incidents is typically not blown off at appropriate intervals, but all at once, in a disproportionate and destructive display. That is why the 4 main elements of Acara should be observed.

1. Maryada/Saujanya (propriety/etiquette/courtesy) *Rama was called “Maryada Purushottam” for precisely this reason

- Polite and Proper speech-i.e. not abusing people for their caste, race or vulnerability

- Respectable behavior in public-i.e. respecting laws, customs & etiquette of a place

- Courtesy to others, especially elders and pregnant women. Chivalry/gentlemanliness/ladylike behavior.

- Consideration for others and their feelings (i.e. respecting queues when possible)

- Respecting those who are elder to you. Your knowledge or intelligence may be greater than theirs, but their wisdom exceeds yours by sheer anubhava (experience). So don’t let ahankar from your college or Veda Patashala studies blind you to their buddhi. Even if they’re wrong, respectfully tell them so . This is maryada

2. Praja dharma (societal duty as citizen worker, businessman, ruler, or priest/teacher)

- Not just being a receiver but also being a contributor to society

- Being a good citizen by paying one’s taxes

- Looking after one’s parents/relatives in old age/need

- Following proper rituals as appropriate for one’s station/occupation

3. Dama (temperance/self-restraint–distinct from and more basic than self-control)

- Restraining one’s greed and animal urges. (greed is the root of sin)

- Care not to cause unnecessary harm to People or Animals or Nature

4. Saucha (cleanliness)

- Not making a mess of one’s self

- Keeping one’s home and streets clean

In short, Acara is good and right conduct. It doesn’t mean being a mahant or mahatma or even a tyagi. It just means behaving well and being a responsible citizen of society (something our NRIs should also remember).

It means showing due courtesy to others (respect to elders and elder siblings, consideration for the weak and vulnerable, concern for the distraught, and fulfillment of basic individual functions to society), it means having good clean habits, it means not littering in public and making a nuisance of yourself, and it means not breaking the law of whatever society of which you are a part.

Thus, in that sense, Acara could never be the highest dharma—but is rather the basic, or elementary dharma—the foundation of dharma. Because dharma itself is subtle (sukshmam), acara must first be mastered. Then and then only can we realize when it should be bent or even broken in favor of the higher needs of Dharma.

Therefore Acara is the way to Dharma, but Dharma is the Path to Achyuta (Narayana).

Cleanliness is Next to Godliness

The average Hindu is very fastidious about Personal cleanliness, bathing once, or even frequently twice a day. So what explains the mess he makes of the country today, let alone himself in public? 1. Loss of civic sense and 2. Lack of consideration for others

Loss of civic sense

The origins of the loss of civic sense lie in the upheaval of colonial rule.Predatory taxation of company and later crown rule ravaged the countryside, driving many off their land and into the cities. Flooded urban areas, unable to cope, could not be expected to manage the basic civic amenities. And as misery loves company, the poverty and slum life became generational.

Thus, the once famously hygienic Hindu (it is the religion of ritual baths after all) became associated with uncleanliness. Cities degenerated, and the rivers became a mockery. But the greatest punishment of poverty is the breaking of the spirit, and with it, goes the dignity of living. Necessity begat squalor. This was further compounded by the blind ritualism that crept into religious practice. Ritual cannot be blind to its effect on society–it too, like Dharma, must adapt to its circumstances as needed.

Kautilya himself stipulated strict laws regarding public hygiene. He mandated fines for:

- “Causing damage to another house by letting urine or dung collect”

- Improper disposal of bodies (i.e. corpses in the Ganga)

- “Throwing dirt on the road”

- “Using a water reservoir as a latrine”

In fact, there are entire sections explicitly on “civic responsibility”, prevention of “nuisance”, and “public hygiene”. How ironic that that the country and civilization most criticized for its lack of civic responsibility and public hygiene had its most famous work on government specifically mandate them…

For the entire state and society to be clean, however, individuals too must also be clean. So let us also emphasize the importance of cleanliness. Indeed, cleanliness (saucha) is one of the pivotal aspects on the path to True Knowledge, as stipulated in the Gita. The Ramayana too described Sita’s “usual scrupulous cleanliness” as emblematic of one of her many virtues. It is for these reasons we posited Saucha as a critical aspect of Acara and emphasized how it furthers the development of Pavitrata (Purity), an important aspect of Dharma. This is because personal uncleanliness not only results in public uncleanliness, but also increases acceptance/proclivity for unclean thoughts and acts. That is why we say Cleanliness is Next to Godliness.

Lack of consideration for others

Consideration for others is an important concept. Lack of it is not always the result of selfishness, in fact, frequently, it’s the end product of self-centeredness. When we are over-involved with ourselves, and unable to step outside and reflect on our own behaviors and practices, we do not think of how we affect others.

So while we have previously written of the importance of atma-vichara (self-reflection) and viveka (discrimination between right and wrong), the third and possibly most important pillar, is willingness to change or at least willingness to hear someone out (suśravasyā ) which ultimately comes from the placement of society above ourselves.

That is the importance of clean living, its evidence in our history, its centrality in our Dharmic culture, and how it can better your life and country today.