Often times, there are instruments that go by many names, and in the process, end up occluding the the essential truth behind it. The next aathodya in our Continuing Series in Carnatic Classical Instruments is one that is typically called shenai or nagasvaram. However, its original name is the one that contains its very nature: Nadasvaram.

Introduction

Na Naadena vinaa geetham na naadena vina svarraha

Na naadena vina nruttham-thasmaath naadaathmakam jagath

Naada roopaha smrutho brahmaa naadaroopo janaardanaha

Nadaroopa Para Sakthihi-naadaroopo Mahesvaraha

Without Nadam, there is no Sruthi, Geetham or Nartthana. Brahma, Vishnu, Siva, Sarasvati, Lakshmi, Parvathi and all the creations in the world are engaged in Nadam.[1]

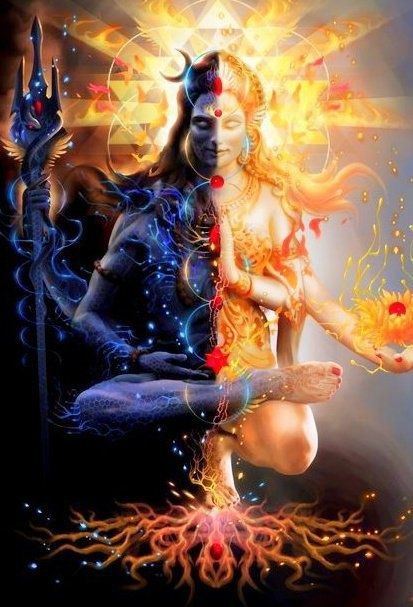

If there is an instrument that cuts to the core of our spirituality, it is the Nadasvaram. As this famous quote from the Brhaddesi explicates, the very name consists of that primordial vibratory sound: Nada (pronounced: naadha) as well as the resultant effect: Svara (note). In that sense, the nadasvaram is the very embodiment of not only saastriya sangeeta, but our bharatiya sanskriti itself. Nada is contained in all things, and all things are contained within it. Nada emerges from the merger of sveta bindu and raktha bindu, personified by Shiva and Shakti.

As stated previously, the Musical instrument (Aathodhya or Vaadhya) [5,110] in our Classical Indic Music is of four kinds: Thatha vaadhyam, Sushira vaadhyam, Avanatta vaadhyam, and Ghana vaadhyam. “They are respectively called stringed instruments, thulai (hole) instruments, leather instruments and metal instruments.”[1, 97] In his exegesis on Naadha, Matanga Muni goes on to note:

naadhoyam nadhather dhaathoh sa cha panchavidhoh bhaveth |

sookshmaschaiva athisookshmascha vyakthovyakthascha krtrimah || ch.1, sl.21

“This (word) naada is (derived) from the dhaatu (root) nadati (to make inarticulate sound) and it is fivefold viz. sooksma (subtle) , atisooksma (very subtle), vyakta (distinct), avyakta (indistinct) and krtrima (artificial).” [4, 9]

As such, the centrality of this word, and by extension this instrument, to our culture is apparent. But what is its history?

History

Sushira Vaadhya (aerophones) are an ancient category of instruments. There are two kinds: those with beating and those that are free. In the first 1, a piece of wood or metal covers the aperture of the wind hole. As such, the reed strikes against the edges of the aperture, which closes periodically. The free reed, on the other hand, freely vibrates within the aperture as it has the same dimensions. [3, 99]

There are numerous names for this type of mechanical reed instrument. These oboe-type aathodyas include the pungi, been, tumbi, nagasar, sapurer bansi, which are used in Northern India. In Southern India, colloquial names such as mahudi, aku (Telugu), peepi/olaga (Kannada), seevali and pambatti kuzhal (Tamil) are more common. [3, 99] However, the nadasvaram is best known by two names:

“In the shehnai and the nagasvaram there are two reeds, with a small gap between them, beating against each other. On the other hand the free reed has almost the same dimensions of the air-hole and hence vibrates within the shallot, without touching the edges.” [3, 99]

Though the word ‘shehnai’ is obviously imported, the nadasvaram instrument is not. In fact, the Brhaddesi (presently dated to 6th century CE) itself is the first available mention of this instrument. Here it is called mavari/madvari. “Other works in which this instrument is mentioned are by Nanya (eleventh century), Sarangadeva (thirteenth century), Vema (fourteenth century) and Chikkabhoopala (seventeenth century), The Kannada poets, Raghavanaka (thirteenth century) in his Harishchandra Kavya, Singiraja (fifteenth century) in his Singiraja Puranam and Govinda Vaidya (seventeenth century) in his Kantheerava Narasaraja Vijaya, give it as mouri; but the Kannada poet-saint-musician, Purandara Dasa, uses also the term mourya in his suladis (which were long compositional types, each section having a different tala).” [3, 102]

Srinatha mentions the naagasvara by name in the 14th Century Kreedabhiramam and as sannayi in the Palnati Veera Charitra. [3, 102] Cognate though it may be, the first confirmed use of the word shehnai is in the 16th century, as attested by the Hindi poet Krishnanand Dasa. [3, 104] Nevertheless, there are other indications of the antiquity of the nadasvaram beyond the textual.

Sculptural evidence is found in a Gandhara relief of the third century, as well as the Veerabhadra temple in Asandi, Karnataka (dating to the early thirteenth). There are paintings in northern India with a nadasvaram type instrument in the sixteenth century itself. [3, 104]

Types

The Nagasvaram is the best known type of Nadasvaram, perhaps because its name tells of its utility. As all naga enthusiasts would know, and as every snake-charmer stereotype of India would indicate, the nagasvaram is often used to attract snakes. [2, 180]

Pungi or Been is a type popular in North India, and which is most associated with snake-charming.

The Tarpo, is a kind that is common in Gujarat and Maharashtra. [3, 99]

Booruga is one type of Nadasvaram that accompanies the main type. [2, 182] It too is commonly used in temple festivities.

Mukhaveena is a small accompaniment to the Nadasvaram. It is a double-reed instrument.

Finally, there is even a variety of bagpipe that has evolved from the nadasvaram. It is called masak in the north. Among Telugus, it is called tutti or titti (meaning bag). “This is the bagpipe of India. While in the pungi and the tarpo, the reservoir is of gourd, in the masak it is of leather.” [3, 101]

Characteristics

There are two essential parts to the Nadasvaram. These are as follows:

1. The reeds: These are two small reeds held together, leaving a small gap between them. The reeds are fixed to the tube of the instrument, either directly or by means of a metallic staple.

2. The tube: This is the main body of the instrument and is the resonator. It is conical in shape, narrow near the blowing end and opening out gradually. Usually, there is metallic ‘bell’ at the farther end. The tube is usually of wood, but may be of metal also. Nagasvarams of silver, gold and even soap-stone are also known“. [3, 104]

In addition to this, are the perforations. There are 7 finger holes down the length of the tube. There are 5 additional holes in the nagasvaram, which are reserved for pitch adjustment rather than playing. [3, 104-105]

Process

There is typically a set structure to constructing most nadasvaram type instruments. While there are double reed instruments (made from palm, cane, etc (i.e. akku)), here we will describe the single reed.

The valve-like reed is attached to a metal tube, which in turn is placed in the funnel-shaped body of the instrument. The length ranges from 25 to 90 cm.

Wax is used to plug holes in order to raise and lower the pitch.

Legacy

“The word ‘Nada’, though represents a mere sound, will only denote a musical sound. Nada is the life and soul of the art of music.” [5, 3]

The Naadhasvaram is as spiritual an instrument as it is intriguing. On the one hand its piercing pitch perforates into our innermost ear, and on the other, its vibration harmonises with our very being. In a sea of sonorous devices, it is the primordial cacophony that creates a vision of the universal beginning.

As such, it is not an aathodya to be casually cast aside amidst casteist wrangling, nor is it one to be dismissed as non-essential to nuanced music. It must be appreciated for what it is, on its own terms, for its actual purpose.

Famous Players

Thiruvavadurai Rajaratnam Pillai

AV Selvaratnam Pillai

Semponnarkoil Brothers

Thiruvizha Jayashankar

Sheik Chinna Moulana

Bismillah Khan

S.Ballesh

Anant Lal

Injikudi E.M. Subramaniam

Bangalore Ramadasappa

Future

The Nadasvaram is the rare instrument that doesn’t readily lend itself to fusion, though there have been some attempts. While it has been appreciated by Jazz enthusiasts as a non-brass precursor to the saxophone, its fundamental quality should be retained.

If there is a quality that best represents the nadasvaram, it is auspiciousness. It is mangalam in mechanical reed form, and thus, is part of a class of instruments called mangala vaadhyam. Hence, the nadasvaram is a fixture not only in temples but at Hindu Weddings as well. In our own Andhra, the tune reaches a climax when the 3 knots of the mangalasoothram are tied around the bride, binding the couple together for 3 births. Such is the auspiciousness attached to this essential instrument of India.

References:

- Iyer, A.S. Panchapakesa. Karnataka Sangeeta Sastra: Theory of Carnatic Music. Chennai: Ganamrutha Prachuram.2008

- Bai, Kusuma K. Music-Dance and Musical Instruments: During the Period of Nayakas (1673-1732). Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrit Bhawan. 1999

- Deva, B. Chaitanya. Musical Instruments of India: Their History and Development. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publ. 2014

- Sharma, Prem Lata. Brhaddesi of Sri Matanga Muni. Vol. I. New Delhi: IGNCA. 1992

- Leela, S.V. Indian Music Series: Book I. Madras: Minerva Publishing House. 1980