Introduction

The word ‘kreeda’ instantly brings to the fore ‘Kreedaabhiraamam”, a classic work by Telugu poet Vallabhamatya. This medieval kavi describes everything from akharas to bull and ram fights and of course, the infamous cock fights which continue to capture the imagination of villagers.

“There were gymnasiums which were called garidis or garidi-saalas where wrestling, duel, and sword-play were regularly practiced, both in the mornings and evenings.”[1, 443]

Both Bhaarathavarsha in general and Aandhra (pra)desa in particular maintained time-tested traditions of kreeda. But kreeda is a comprehensive category including both martial Sports and childish games. This article will concentrate more on the latter, hence the title: Aatalu.

Games (Aatalu)

The burden of performing ones dharma, or even the basic duty of work, can prove onerous and dreary to even the most dhaarmik of souls. All work and no play, after all, makes Jakkana a dull boy. In the innermost kernel of humanity is the very human need for play and divertissement. Nothing says joie de vivre more than a rousing game of pichkaris during Vasanthothsava. However, some endeavours are better suited for special occasions. What about the more quotidian of engagements? Here is a quick list of games that were common in Ancient Aandhra (and by extension, Bhaarathavarsha).

Kite-flying and playing with tops were also common. A quick listing is as follows:

Raagunjaupeyaunjaulaata, kundena, gudigudi-gunjainbulaata, aplavindulayaata, sarigunjulaata, citlapaatlaata, gorantalaata, cerabonlalayaata, cappatlupettuta, gidugid-gudikkonnuntaa, and daagudumutataata. Of these, some are comple-tely forgotten, and others, likegudigudigunjamu, citlapotlaata, kundena, and daagudumootalu (hide and seek), are popular in the countryside even today.” [1, 444]

Games of dexterity often took prominence.

Acchanagandlu (marbles) was a favourite and was played by tossing them up and catching them on the back of the hand. It is played by two people or more.

Aristocratic families gravitated more to dice (anjisogataalu)and gambling (nettamu).“Six-sided dice have been found in the Indus cities, and the “Gamester’s Lament’ of the Rg Veda testifies to the popularity of gambling among the early Aryans”. [3, 207] Dice was played on a palaka (board) and is mentioned in the Bhojaraajeeyam and Simhaasana-dvatrimsika (telugu rendition of Vikramaditya’s famed legends). [1, 445]

“The word aksa in the context of gambling is generally roughly translated ‘dice’, but the aksas in the earliest gambling games were not dice, but small hard nuts called vihbheesaka or vibheesaka; apparently players drew a handful of these from a row and scored if the number was a multiple of four”. [1, 207]

A synonym for dice, that became (in)famous in later periods, was dhyootha. The episode of the Mahabhaaratha that most embodies this is of course “dhyoothakreeda”, wherein the tragedy of Yudhisthira’s addiction to gambling is put on full display. There is a difference between a friendly wager and ruination. It is why gambling, like alcohol, is strongly controlled and even discouraged.

“Later, oblong dice with four scoring sides were used; like the European gamester the Indian employed a special terminology for the throws at dice: krta (cater, four), treta (trey), dvapara (deuce), and kali (ace). So important was gambling in the Indian scheme of things that these four terms were applied to the four periods (yuga) of the aeon.” [1, 207] Interestingly, an ancient Vedic Raajaratna was appelled Aksavaaapa (literally dice thrower). He was the comptroller-in-chief and also the organiser of gambling bouts.[1, 208]

Bullfighting was common in Andhra. However, the lead form was undoubtedly the Jallikattu of Tamil Nadu , which was also en vogue. “This sport did not closely resemble the Spanish bull-fight, where scales are heavily weighted against the bull, for here the bull appears to have had the advantage. The fights were popular among herdsmen, who entered the arena unarmed, and ‘embraced the bull’ in an attempt to master it, rather like the cowpunchers of an American rodeo. They made no attempt to kill the bull, and it was not previously irritated, but the bullfight was evidently a sport of great danger for the poem contains a gory description of a victorious bull, his horns hung with the victorious entrails of his unsuccessful opponents. The bullfight was looked on as an ordeal to test the man-hood of young men, since it is stated that the girls who watched the performance would choose their husbands from among the successful competitors in a sort of Tamil Svayamvara.” [1, 209]

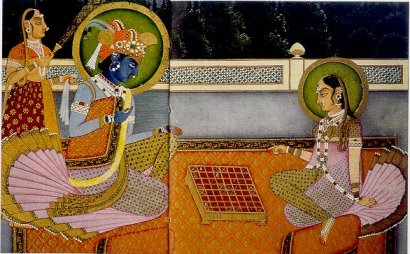

Some pursuits were more akin to dances. The Kreedaabhiraamam describes Kandukakreeda/Kandukanrtta, wherein dancers play with a ball. This is echoed in King Peda Komati Vema’s Sangeetha-chinthaamani. He delineates the interaction as a whirling movement (bhramari), wherein the ball is beaten back-and-forth through movements of the hands and feet. [1, 431]

Cards

“Patrakrida, or Cardplay came to know as “Ganjipha” the later half of Medieval period. Though there are references to Patrakrida in works such as Kamasutra; no manual survived from the past. ” [4]

As with Kalamkari, Ganjifa shows how distorians of the day have long attributed a foreign origin simply on the basis of a modern etymology. Ganjifa the word certainly stems from the Persian Ganjifeh (as with Qalam), but the sport of cards was originally called Patra Kreeda (as Kalamkari is connected with Odisha’s Patachitra, still in currency today).

“The six texts that deal with card play its various dimensions that survive today are- Ganjiphakhelana, Ganjipha Khelanakrama, Sritattvanidhi, Kridanidhi, Kridakausalya, Cetavinoda Kavya and Kridakausalya” [4]

The Dashaavathaara Patra-kreeda is the most famous even today. How this eventually evolved into the modern 52 card deck, is another matter. No doubt, as with Flamenco music, the Roma (Gypsies) who are famed for tarot cards, are at the centre of this cultural exchange.

Board Games

Board games proper are a category of their own, and true to the homonym, are excellent games for the bored. They are divided into two basic categories: 1) Pieces are moved alternately by each player and 2) moves decided by throwing dice, etc. [2, iv]. Some are more commonly known (pachisi), but more interesting still, are those traditional games almost forgotten today.

Dhadi. Also known as the ‘Attack game’ it is played on a board by 2 persons, who alternately insert 11 pieces each. “If one can put three pieces in a line it can kill one of the opponent. Whoever loses their pieces loses the game and [the] other is the winner.” [2, 55] The game design is somewhat unique over a number of interlocking quadrants. Variations can be found in China and Korea. [2, 56]

Wana Gunta or Vaamana-guntalu is a prominent game that is played on planks (two foldable ones in this case). There are 7 or depressions on each plank and is played by two people. The object of the game is to deplete the pebbles or tamarind seeds in the other side’s depressions, [1, 446]. Similar mockups can be found in Petra and ancient Nabatea, and are known as Mancala. [2, 62]

Ashta chamma

A moderately-known game played on 5×5 or 7×7 grid boards, Ashta Chamma refers to the Eight cowries (or tamarind pieces) deciding moves for players. It can be played by 2, 3 or 4 people.

- “Starting points are marked and moves of pieces are anti-clockwise on the outer and clockwise in the inner circles.”. [2, 62]

- In order to commence, one must get 4 or 8 points from a throw.

- The first piece enters the inner circle only after killing at least 1 piece of the opponent. If not it remains in the outer squares.

- There are 5 crossed or safe spaces that act like a fort.

Interestingly enough, a number of forts in Trilinga desa feature artwork of Ashta Chamma. There are other Telugu games as well.

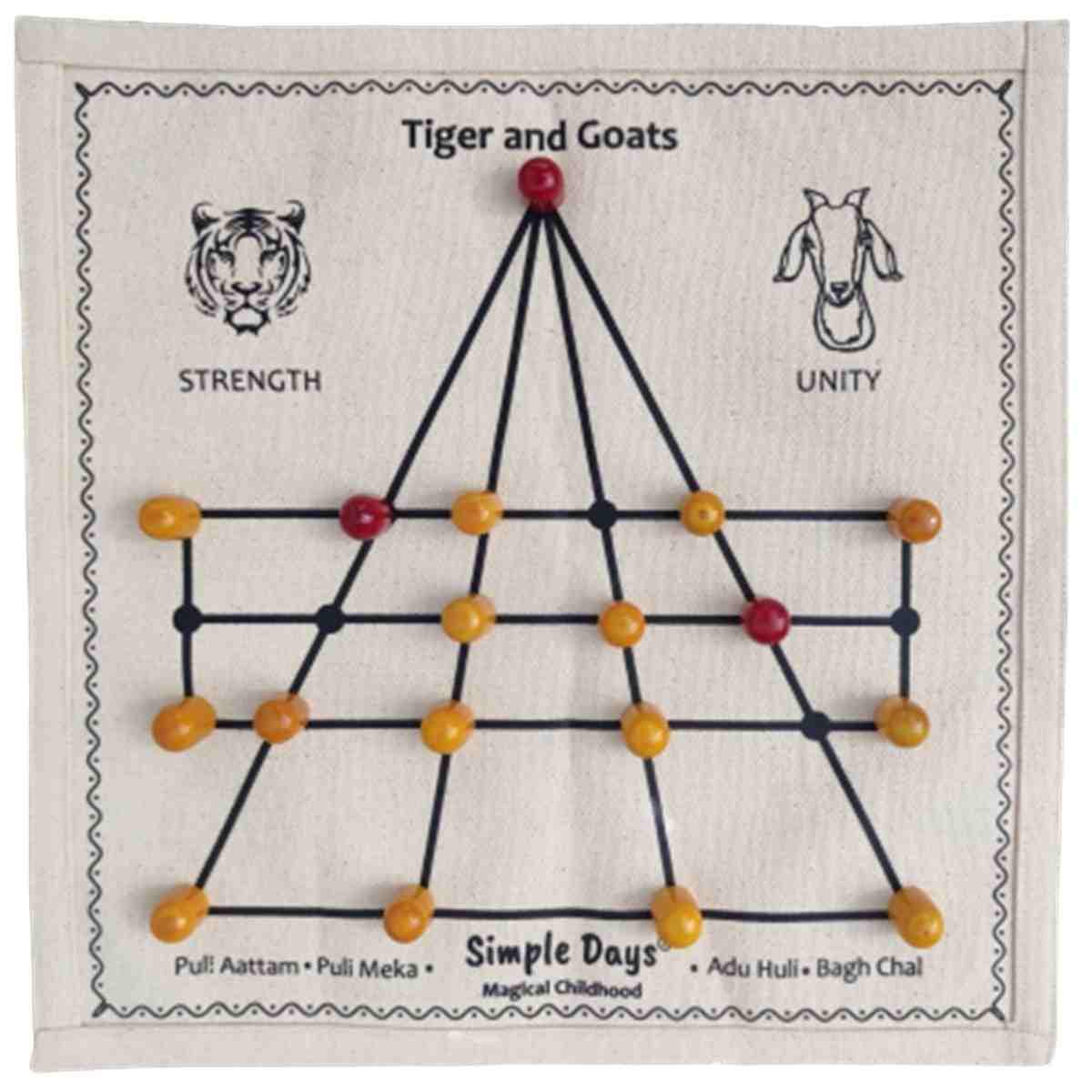

Puli Joodhamu

Puli-joodhamu or Puli-mekalu (Tigers & Goats). Played in other parts of India as well, it was popular among young and old. There are 2-3 large stones (tigers) and 11-15 small stones (goats), or 21 goats in other versions. [2, 51] The goal of the game is for player one to eat up player two’s goats.

- Goats should try to hem in the tigers movements

- Tiger is stationed at the triangle apex (kona) & should not be occupied by a goat

- Tiger can leap over 1 goat at a time. [1, 446]

Evidence of this game can be found at the Govindaraajaswami temple, where it is shown as 3 tigers and 16 goats. This makes for a faster and more intense game. [2, 53]

Traditionalism notwithstanding, there are 3 major games that have made a world-wide impact even in the modern world. The first is known to us today as Parcheesi.

Pachisi

“’Pachisi’ is an ancient board game and its very name pachis meaning twenty-five in Hindi confirms its origin from India. It was sometimes called the national game of India.” [2, 31] Pachikas (dice bars) were often used instead of cowrie shells. There are similarities to the game of Patolli, played by the Aztec Civilization of Mexico in the 15th Century. It was introduced to Britain from India in 1896 AD. [2, 39]

Anglicised today as Ludo or Parcheesi, Pachisi finds evidence in India at the Gudimallam temple of Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh. There on the walls, one will find evidence of it as well as Chess and Dhadi. [2, v] Additional proof is adduced at Gandikota, Kondaveedu, Undrukonda, Rachakonda, and Devarakonda.

- It was played on a board in the shape of a plus sign (not unlike the chaupad). This was called char koni (4 points).

- Moves are based on throws of dice or cowrie shells. Pieces that are captured are returned to the centre to start again.

- The player or partnership that completes the course and returns first to the centre space, wins. “Cross-marked squares along the course represent castles in which the occupying pieces cannot be captured. An occupied castle is open to the player’s other pieces or those of his partner but closed to those of his opponents.” [2, 32]

- “Sixteen beehive shaped pieces are used, four in black, four in green, four in red and four in yellow. 7 cowrie shells provide the element of luck or chance, that when thrown, indicate the numbers according to the rules of the game. The numbers indicate the squares one can move counter clockwise. “ [2, 33]

- Players may sometimes be given a grace, allowing a new piece to star over from the charkoni.

“Govindarajaswamy temple is located in the Hindu holy city of Tirupati., which has markings of Pachisi, Dadhi, Tiger and goats game, etc.” [2, V]

Nevertheless, there are two leisure pursuits that have stood the test of time and remained famed as uniquely Indic contributions to the modern world; these are Chathuranga and Mokshapaatam, better known as Chess and Chutes & Ladders.

Chess

“Chess is the oldest ancient Indian board game and some claim that it was played for almost 4000 years.” [2, 43]

Chess is a veritable category of its own. A game that has spawned a hundred variations and a thousand spinoffs (with license for hyperbole), it is truly the game of kings and queens.“Chaturanga was the earlier precursor of modern chess because it had two key features found in all chess variants namely different pieces had different powers and the victory in the game depended on one piece, the king.” [2, 44]

The earliest chess pieces can be found at “Nashipur in Murshidabad district of West Bengal that can be dated to around 900 AD”. [2, 1] However, literary and epigraphic evidence dates further back.

“Chess was developed as a war game in ancient India and the chess board has been compared to a battle field and each side now has pieces (16 white and 16 black) which are compared to contending armies. The players think in terms of attack,defence, maneauvers, captures, ambushes and many other terms suggesting a combat.” [2, 45]

Chess developed “regional variations in the game such as Persian, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Malay and Myanmar etc. For example in Persia the chess came to be known as ‘shatranj’…Chinese chess (Xianggi) had nine files and ten ranks as well as a boundary river between the 5th and 6th ranks which limits access to the enemy camp…Shogi is the name for Japanese chess and it has 9 X 9 board with some differences. Korean chess is known as tyang-keui”. [Reddy, 46] The latter builds off of the Chinese version, except the river is ignored and the king is at the centre of the camp.

“The first version of chess appeared in North Western parts of India during the Gupta period 94th to 6th century AD) and then spread to Persia where it was known as ‘shatranj’.” [2,iii] Modifications took place both in Paarasika-desa as well as elsewhere: “For instance, a river was interposed between the two sides of the chess game in China, which made the game slower but more complex. It is interesting to known that the game of chess survived among the hundreds of board games invented and played throughout human history during the past 1500 years. This game has thrived in every culture it has touched and it has become the national game in undivided Russia. Games and other theories are woven around this game, which originated in ancient India as a war game.” [2, iv]

Like many aspects of culture, the game of chess has undergone evolution over millennia. “The game of Chaturanga was also referred to as Chaturaji or four kings.” [2, 4] This variation is most commonly seen due to the usage of the Chaupad as board. “Amarakosha, which is a Sanskrit thesaurus that was compiled in the fourth century AD, explains the functions of each of these four members and their mobility. [William] Jones quoted from this book that explains some of the general rules of the game: such as ‘the pawns and the ship can both kill and may be voluntarily killed, while the king, the elephant and horse may slay the foe, but cannot expose themselves to be slain’ and so on (Jones 1817 AD).” [2, 4]

“Kridakausalyam is a Sanskrit text with Hindi translation written by Pandit HariKrishna Sarma (1982) that deals exclusively with ancient Indian board games included games such as pachisi, chess, tiger and goats game etc. This book on games is a chapter from a larger book titled ‘Brihajyothi-shyaarnavam’ which was first published by the same author in 1881. Kridakausalyam was first published in 1934 and reprinted in 1982.” [2, 4]

This book contains an anecdote where goddess Parvathi defeated the god Shiva in a game, causing him to sulk and go into the forest. It is Ganesha that brings him back to be a sportsman. [2, 4]

“The book ‘kridakausalyam details why it is important to play the games not only for entertainment but also to improve cognitive skills. There are twelve chapters each dealing with one game and explains how to plan a win in the games. It is interesting to note that chess was played differently on 64, 100 and 124 squares grid.” [2, 5]

“The number of players could be either four or two and this fact was confirmed by Al-Beruni in the 11th century AD. In some forts such as Rachakonda there are designs of a game with 100 squares and this must be one type of chess game played in ancient India.” [2, 5]

The village of Kuchipudi, in Repalle (Guntur District), contains a donation to a temple by a noted chess professional named Veerayya. It specifically mentions the name chaturanga. Another inscription at Koppulu village of Kadapa district refers to Bodducherla Thimmanna who was a chess enthusiast appreciated by Vijayanagara Emperor Sadashiva Raya, in 1544 AD [2, 6]

Moksha Paatam/Kailaasam

Rebranded as Snakes & Ladders or Chutes & Ladders in the Europe and North America, it is known to most Bhaaratheeyas as Moksha Paatam or Kailaasam. Fairly self-explanatory, it too is played by 2 persons and the object of the game is to start from the bottom and reach the top first. Players have numerous obstacles to overcome, and the “throw of cowries decides the number of moves and the presence of ladder helps to go up and the snake puts break and pulls one down.” [2, 57]

The Classical Indic Version—that is, Moksha Paatam—featured snakes as vices and ladders as virtues. Also known as Vaikuntapali and Paramapada Sopanum, it focused on karma, and demonstrated how vices such as lust and passion destroy, and how a person obtains moksha by virtue. Today, the game is played with 19 chutes and ladders and100 squares (first 1 is red and last one is green). [2, 58]

Conclusion

The 4,500 year-old Royal Game of Ur from ancient Mesopotamia (Iraq). The world’s oldest playable board game. Discovered by Leonard Woolley during excavations at the Royal Cemetery of Ur in the 1920s. The hollow box is made of wood and shell. Image: British Museum.#Archaeology pic.twitter.com/ixWTGQYdXt

— Alison Fisk (@AlisonFisk) November 25, 2021

Leisure pursuits are an intrinsic part of civilized life. After all, one works to live as opposed to the modern era where seemingly we all live to work. But an idle mind is a devil’s (or asura’s) workshop. Without constructive recreation to occupy the minds of men and women, they may soon find themselves going wayward. Dharmic society cannot be burdensome and rigid for the populace at large, nor can it be permissive either. A respectable and contented society has a balance of rules and recreation. Kreeda or Aatalu, therefore, are the sine qua non of honourable entertainment.

Leisure cannot always involve the fine arts or even the crafts. Sometimes, life needs a little bit of fun to add to its kaleidoscope of colour. The traditional aatalu of ancient Aandhra, and by extension, India, not only had a tremendous impact on the world, but make for enjoyable pastime even today.

References:

- Sarma, Somasekhara M. History of the Reddi Kingdoms. Waltair: Andhra University. 2015

- Reddy, Raja Deme & Samiksha Deme. Ancient Indian Board Games. Delhi: B.R.Publishing. 2015

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. Delhi: Rupa & Co. 1999

- B. Ramadevi, Patra Krida – Ganjifa Card Play in Sanskrit Literature. Chennai: Rasa Publ. 2017