“I am yay man of conshunce” (sic), “I have to follow my haaart” (sic), “I have a conscience, don’t you?? ”…three of the many tired bromides offered by our senti intellectual elite—yes, even on the conservative right. But the reality, my friends, is that such men of conscience will be the death of us.

While such preferred actions are couched in the verbiage of conscience, they are really substituting conscience for sentiment, because, let’s face it, we Indians are a ridiculously sentimental people. While the opponents of all that is good and sacred in this world may feign various sentiments often as a ruse, when push comes to shove, they show no such ambivalence.

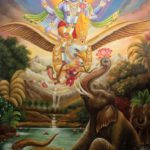

History itself has shown time and again how such men of conscience conveniently hear that little voice at the worst possible time. The Mahabharata, and the Gita in particular, are in fact a specific repudiation of such senti based decision-making. This is of course not to say that we shouldn’t have a conscience—we absolutely must.

Pleasure without conscience is one of the greatest sins against humanity, because it leads to exploitation, especially of the innocent and unwilling. But what I have a problem with, and as the Gita itself explicitly rejects, are these self-proclaimed men of conscience who conveniently discover it at all the wrong times.

Where was Arjuna’s conscience when Bhishma’s conscience permitted Draupadi’s disrobing? Where was Yudhisthira’s conscience when he agreed to the unjust wager of Draupadi?

Where was Arjuna’s conscience when Drona participated in the unjust killing of mighty Abhimanyu?

Fortunately for Arjuna, and the Pandavas, Krishna was there to talk some serious sense into him. Thus the issue with these so-called men of conscience is not so much that conscience itself is wrong–in fact, it is a critical first step towards the path of dharma–but rather that conscience must be entwined with principle.

Conscience must not become an excuse for sentiment. Indians are notorious not only for their prickliness but the ridiculous extents to which their sentiments can extend, in all things. But this sentiment or moha cannot blind us to balancing all interests, least of all, the right course of action. For when this happens, all of society suffers.

A political commentator I greatly respect—a man who has been able, in the darkest of days, to get us all to put aside differences of caste, creed, and sampradaya to see the greater good— recently engaged in similar such rumination, because of his personal attachment to a friendship with a particular MP. But said MP had no compunction in choosing to join the most anti-national party in India and adding legitimacy to the most corrupt administration in India’s history—and this is only the confirmed of his crimes, among many alleged ones. While I believe the noble commentator will make the right choice in the end (and not support this MP)—this episode is nevertheless testament to how we are all—even the very tall among us— subject to this, the greatest temptation of all—moha (attachment). Fortunately, Yuktata (or justice) is the cure for it.

Our conscience (or sentiment) is often stoked to blind us to the regimented and orderly application of justice. Feelings are used to deceive us of the danger that lurks should we fall for the ruse. When Sun Tzu famously wrote that “All warfare is deception”, should we not be unsurprised when this is applied in politics? Simply because someone presents himself/herself in a pleasing, charming, and intellectual manner, does not mean we should judge the book merely by its cover. Actions are what speak volumes, and it is through action and intent that we administer justice. Actions and intent must be judged against the common good.

While this well-known blogger certainly does not deserve association with the likes of the Prashant Bhushans and Arundhati Roys of the world (in fact, he is among their greatest opponents), the reality is they, unlike him, specifically tout themselves as men and women of conscience …and we all know how selective their conscience is. While I must reiterate that said blogger remains in the ranks of the very tall among us, this particular development goes to show just how susceptible we all are to moha, whether brave Pandava or brilliant columnista.

So the next time you come across another such man (or woman) of conscience (however temporarily they may be affected by moha), ask him if his conscience isn’t merely a way to avoid having to do the difficult thing—i.e. making the right choice. Good friends may be hard to come by, but an ignorant friend leads to destruction. And supporting such a friend in their adharmic escapades is also wrong. Attachment to a famous friend is still attachment.

We are often in our lives misled by the charm and charisma of the fair among us. The smooth talkers, the sophisticated davos men, and ye ever present “liberal intellectual” who take pleasing forms to deceive us all, as they forge their rings of power.

But the reality is our judgments and even loyalty to such people should be premised on principle and gauged not by how they make you feel or how much you enjoy their company, but by whether their actions and policies are in line with the common good. Thus, such blue-eyed boys (and girls) may often seem fair, but mask a foul agenda.

I will end with a line from one of the most beloved stories of our time, the Lord of the Rings. In it, one of the characters said the following:

“I think a servant of the enemy would look fairer, but feel fouler”

…the next time ye men of conscience waffle in the name of moha, remember this wisdom, for therein lies, yours and all of our salvation.

And so my friends, rather than being a man of conscience, be a man (or woman) of principle. Because while our conscience may sometimes betray us, virtuous principles never will.