Continuing our Series on Buddhist Personalities is a follower of the Buddha so eminent, he became a namesake of sorts: Buddhapalita (Buddhapaalitha).

“the Maadhyamika school of Naagaarjuna came to be divided into Praasangika and Svaatantrika schools expounded by Buddhapaalita and Bhaavaviveka respectively, and both of them were natives of Aandhradesa”. [1, 65-66]

Although there is copious information about Bhavaviveka, background is sparse on the life and times of Buddhapalita.

Background

Buddhapaalitha is a name literally meaning “One Protected by the Buddha”. It is a known fact that the Mahasanghika (Mahayaana) tradition of Buddhism literally deified the Thathaagatha. In contrast, the older tradition of Sthaveeravaadha (Heenayaana) saw Buddha as a man who attained perfect enlightenment.

“Though Asvaghosha, the court poet of Kanishka used the word Mahaayaana, he did not use the term in the sense that it was a separate system. He used the word Mahaayaana for Buddhism itself as the religion of the perfect one.” [1, 31]

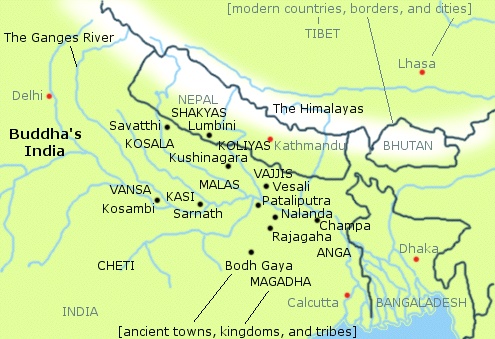

In the action and reaction between the two, a variety of sub-sects and schools arose. Nevertheless, prominent among them all was the Praasangika system, and its prime proponent, Buddhapaalitha. He was a native of Srikakulam district, Andhra Pradesh.

“Buddhapaalita is said to have been a native of Dantapura. The place is identified with Kalingapattanam in Chicacole [Srikakulam] district. It was the capital of ancient Kalinga and was called Dantapura in the Ceylonese chronicles as it was connected with the tooth relic that was carried to Ceylon.” [1, 82]

Uttarandhra today is at the crossroads of the Telugu and Odia-speaking worlds. In fact, it is often called Kalingandhra for this reason. Nevertheless, our personality today is identified as a southerner rather than an easterner, and Srikakulam is very much in modern Andhra Pradesh.

“Buddhapaalita and Candrakeerti are called Praasangikas and their method is designated as Prasanga (reductio ad absurdum), whereas Bhaavaviveka is called Svaatantrika and his method, Svantantraanumaana (independent, positive rea-soning). This svaatantrika school came later to be subdivided into Yogaacaaraa-Svaatantrika-Maadhyamika and Sautraantika-Svaatantrika-Maadhyamika, the one maintaining self-awareness (svasamvedana) while rejecting the external world and the other rejecting self-awareness and admitting the external ob-jects established through their particulars (Svalakshanas). The first sub-school is represented by Saantarakshita and Kamalaseela, while the second, by Bhaavaviveka himself.” [2, 3]

Though not much else is known about Buddhapaalitha, he is said to have been a student of Sangharaksitha. [1, 82]

Achievements

Buddhapaalitha is famous for establishing the Praasangika sect of the Maadhyamika school of Mahayaana. He was an admirer of Nagarjuna and a proponent of Prasanga, which in the Tarka tradition, refers to reductio ad absurdum.

His main achievement was authoring a commentary on Nagarjuna.

“Buddhapaalita was an ardent follower of Naagaarjuna, and wrote a commentary named Madhyamakavrtti on Naagaarjuna’s Madhyamaka Saastra. Buddhapaalita held prasanga to be the real method of Naagaarjuna and Aaryadeva. The method is to lead the opponent to an absurd position and prove him wrong. His school therefore came to be known as the Praasangika school of the Maadhyamika, which is given an exposition in his Madhyamakavrtti.” [1, 83]

Though criticised by Bhaavaviveka, he was later defended ably by Chandrakeerthi. Indeed, in the battle between the two, for better or for worse, it was the latter which prevailed.

“It is the Praasangika school of Buddhapaalita and Chandrakeerti which has held its sway over the other school all along, to the extent of being treated as the Maadhyamika system proper, not only by the Praasangikas themselves but by the opponents of the Maadhyamika system as well.” [2,2]

Legacy

Buddhapaalitha was a Maadhyamika. The legacy of this school cannot be denied, nor can its impact on Indic thought be gainsaid.

“the Maadhyamikas may be viewed as the most clear-headed group of Indian philosophers. But for all their clear-headedness, they happen to be the most misunderstood of them today. A careful scrutiny of their primary sources, as also of those of their rivals, confirms the classical interpretation that their philosophy, style soonyavaada, is absolute Nihilism rather than an Absolutism or Absolutistic monism, as commonly believed in respon-sible circles. ” [1, 3]

Whether this is in fact true or not, it does bring to light an important issue that is all too often elided: what is the impact of lokayatins or even flat-out Nihilists in appropriating and re-deploying Buddhist Philosophy?

“The Chinese traveler, Yuan Chwang writes that in Orissa the monks studied Heenayaana and hated Mahaayaanists as ‘sky flower-her[e]tics as bad as Kaapaalikas.” [1, 33]

Our old nemeses, the Kaapaalikas, make their entrance once more in the practice of philosophy and logic. Lokayata has already demonstrably hid behind astika Vedic cover, but to what extent it has flat out subverted the noble religion of the Eightfold Path is little discussed in polite circles today. To understand the how and the why necessitates studying the various strands of Bauddha Dharma.

Vajraayana is a popularly cited tradition of Buddhism that has received plenty of superficial attention, but insufficiently deep-study in astika circles. The origin of this Tibetanised rendition has included, officially, the Bon faith. But what was the ancient nature of this pre-Buddhistic religion, and what connection does it have with the Kaapalikas? Further evaluation might indicate and account for emerging controversies in the present time.

“It is seldom appreciated…that in the Indian tradition Nihilism has been in the air from Buddhist, rather pre-Buddhist times, to even slightly post-Maadhyamika times.” [2, 4]

Indeed, it has long been argued that Western “Enlightenment” Thinkers have been surreptitiously drawing from the Buddhist tradition:

I will cite evidence that Jesuits brought Buddhism from China to Europe and Hume studied that in formulating his theories. https://t.co/KCRjQQ2fQS

— Rajiv Malhotra (@RajivMessage) May 6, 2019

“We are inclined to believe that the classics are nearer the truth about the Maadhyamika’s position than the moderns. Philosophical Soonyavaada is a form of illusionism and nihil-ism: it is absolute ontological nihilism as distinguished from the destructed nihilism of Harivarman; the soteriologicl nihiism of Arthur Schopenhauer and Eduard von Hartmann; and the critical nihilism of Jayarasi Bhatta, author of the Tattvopaplavasinha, the only extant work of the Lokaayata school. Again, the Hindu, Jaina and Lokaayata schools of philosophy (barring of course Jayaraasi Batta) on the one hand and Mahaayaana and certain forms of Heenayaana like the schools of the Saamiteeyas and Vaatseeputreeyas on the other, are noumenalists; the bulk of realist and idealist schools of Buddhism are phenomenalists; and the Maadhyamika school is illusionist and nihilist.” [2, 5]

Nihilism comes from the latin term Nihil, meaning “nothing”. In essence, if nothing matters, then one may do what one pleases. Its connection to Soonyavaadha (the central doctrine of the Maadhyamika school) and the misinterpretation of this theory to mean “nothingness” rather than “emptiness” is all too apparent. This is very much in line with that old bugbear, the Charvakas. After all, if nothing matters, pleasure becomes the prime pointer. It is for this reason, the doctrine of the soul and its place becomes so crucial. Much that is ascribed to the Buddha is not in fact his word:

“The Buddha talks so much of the no-soul (anattaa) that he has come to be regarded as an advocate of a no-soul doc-trine second only to Caarvaaka. But to say that he was out and out a repudiator of the existence of soul does not appear to be the whole truth, despite all avowals to that effect on the part of the bulk of his followers and modern Buddhologists. It has been noted by certain competent scholars that such an absolute statement as ‘there is no soul’ or ‘ the soul does not exist’ is conspicuous by its absences in the Paali canon. On the other hand, what occurs therein, and frequently, is that the body is not the attaa, the senses are not the attaa, the sense-objects are not the attaa, the five aggregates are not the attaa, and so forth. In fact, the Buddha appears to lament the fact that the aggregates are usually mistaken for the soul and to approve of detachment therefrom:

“O Bhikkhus! matter/form is non-eternal, what is non-eternal is suffering, what is suffering is no-soul (anattaa), what is no-soul should be viewed as such after duly realizing ‘this is not mine, this is not me, it is not my soul'” (netam mama, neso’ham asmi, na me so attaa). This statement is repeated in respect of the other aggregates as well. It is also added to the first statement, the one vis-a-vis matter/form, that so realizing, mind stands fully detached and liberated. Another statement is : ” O Bhikkhus! matter/form is anattaa…feeling is anattaa…idea is anattaa…volition is anattaa…sensation is anattaa.” In such contexts, the target of attack seems to be not the theory of soul but various types of materialism.” [2,15]

“Sankara refers to such materialists thus: ‘Some materialists take the body to be the soul….some other materialists take the senses to be the soul, still others take the mind to be the soul, many other materialists take the intellect to be the soul, and there are certain materialists who take to be the soul the unmanifest within the intellect identifiable with Ignorance.’ Here, too, one may read a repudiation of each one of the five aggregates on the one hand and each one of the five sheaths listed in the Taittireeya Upanishad from matter to intellect on the other, being regarded as the soul. Thus, it is not the existence of the soul, which is denied in the Paali canon or by the Buddha but the identifica-tion of the non-soul with the soul. The Buddha exhorts us to have this attitude towards the three lakkhanas (khadhas, dhaatus, and aayatanas): It is not mine, it is not me, it is not my soul (netam mama, neso ‘ham, asmi, na me so attaa).” [2, 16]

This thesis has been asserted elsewhere as well:

“The idea of the aatman as the impersonal universal aatman did not become dominant in India until some time after the eighth century C.E. Before then, throughout the Buddhist period, the dominant idea of the aatman in India was that of a perma-nent personal aatman. Judging from from their writings, the Indian Buddhist teachers from Naagaarjuna to Aaryadeva to Asanga to Vasubandhu to Bhavya to Candrakeerti to Dharmakeerti to Saantarakshita thought that the Buddha’s anaatman teeaching was directed against a permanent personal aatman.” [3, ix]

In short, how could a religion which asserted the reality of reincarnation and transmigration deny the existence of an over-arching spirit that exists as the experiencer? It is understandable if the personal aatman is denied, but whither the denial of a paramaatman? Non-commital to the credo of a dualistic creator God/Demiurge is one thing, but not the existence of a supra-soul that is the experience of all things. It is an absolute non-dualism that is misconstrued as absolute nihilism (for those more concerned with material pleasures and human exploitation).

Much is made of the discussion of Braahmanas in the Dhammapada or Buddha’s conservative views on varna or Vedanta. Some even question whether Buddha’s Eightfold Path is a new religion. But such commentators ignore the reality of the Paali Canon (Samyutta-Nikaaya (I. p.169), which puts to rest such false, self-serving assertions:

“Do not think or Brahmin, that you obtain purity by putting wood in the fire… I have renounced, O Brahmin, the Burning of wood…I follow, as an an Arahant, the way that leads to brahman. Your pride, O brahmin, is a heavy burden to you. Your anger is the smoke, and in the ashes rest your lies. The tongue is the sacrificial spoon, and the heart to fire altar. The (phenomenal) aatman, is perfectly controlled, is, for man his light.” [3, 179]

Kaapaalikas, Aghoris, and Asura-worshippers of all sorts are not Dharmics. In fact, on the pretext of Spirituality, they engage in all forbidden and despicable acts to attain materialistic “spiritual” powers. They practice ritualistic-materialism, rather than religious spirituality. They and their acolytes and their apologists are all despicable, and the time has come for true dharmics to separate themselves from them.

What place Buddhapaalitha has in this Samudra Manthan, has yet to be unveiled. However, the religion of the Vedas and the religion of the Buddha may seem diametrically opposed, but at the heart, they possess the core saamaanya dharma of compassion and cleanliness. Those who do the opposite and worship malignant and malefic deities can cry “Christian missionary!” all they wish; the reality is that those who propitiate Asuras, preach “Beef in Vedas“, and publish articles promoting go-bhakshya are more missionary and mleccha than any true dharmika, of whatever sampradaya. Buddham sharanam gacchami.

Sanctity of the Cow in Ariya Dhamma

References:

- Sitaramamma, J. Mahayana Buddhism in Andhradesa. Delhi: Eastern Book Linkers. 2005

- Narain, Harsh. The Madhyamika Mind. Delhi: MLBD. 1997

- Bhattacharya, Kamaleswar. The Atman-Brahman in Ancient Buddhism. Delhi: MLBD.2017