An appropriate companion article to Janapada Sangeeta is our next one on Janapada Nrtya.

Dance is often seen through the lens of modern unrestrained dance forms or the more formal and even devotional arts, such as Bharathanaatyam, Kuchipudi, and Perini. But in between pop and classical is folk.

Folk dance has always had a central place in the Andhra desa. However, unlike modern indologists, who learn more and more about less and less, our traditional performers knew that folk dance forms of the janapaadha janas and girijanas had an intrinsic connection to the classical tradition.

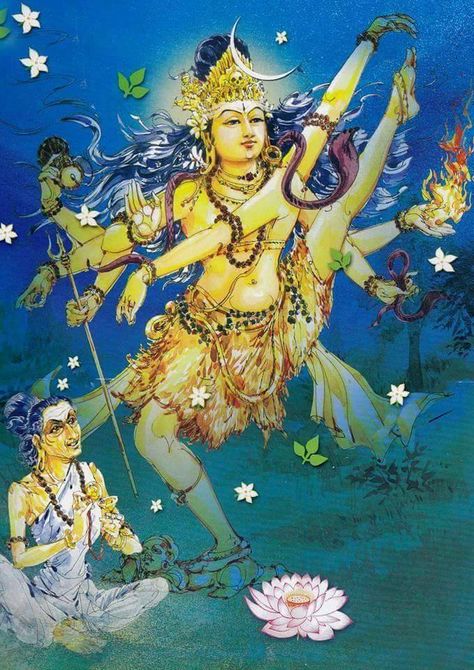

History

“Brahmaa thaala dharo-hariccha patahee

Veenaa kara bhaarathee ||

Vamsagnyow sasi bhaaskarow

Srthi dhaaraha ||

Siddhaap Saraha kinnaraahaa

Nandee Bhrungiritaadi mardala dharaha ||

Sangeethako nardaha

Samboho nruttha karasya mangalathanoho ||

Naatyam sadaa paathunaha ||

With Brahma providing the beat, Vishnu playing on the mridangam, Sarasvathi playing the Veena, Surya and Chandra playing the flute, Devas and Apsaras providing the Sruthi, Nandi and Brungi playing other instruments, Narada singing melodiously, every one enjoyed the celestial dance of Siva.” [2]

Music and Dance are undeniably connected. It is for this reason that the performance arts themselves are categorised under Gaandharva Veda or Gaandharvam. The greatest treatise on Histrionics was the Natya Sastra of Bharatha Muni.

”The word natya is derived from the nata meaning avaspandana i.e. quivering”, whereas the word nritya is derived from nrit, meaning gatravikshepa or throwing of the limbs. Again it should be observed that natya is meant for arous-ing aesthetic sentiment or rasas, whereas nritya is meant for arousing moods or bhavas.” [3, 61]

“Naatya proper or Histrionics” [4, 97]

Alternately, per Bharatha muni, nrtta is pure rhythmic dance, nrthya is dance in general, and naatya is histrionics (performance). Hence the correct terminology for dance is nrthya. Naatya encompasses performance in general, and naataka refers to dramatics and dramaturgy. Incidentally, much like pattachitra has become the calling card of Odias, but was originally a Classical Indic Art, so too was Yakshagana (today a calling card of Kannadigas who preserved it) an all India classical performance art.

@AndhraPortal This might interest you. There is a footnote in Dr S V Joga Rao's "Andhra Yakshagana Vangmaya Charitra". We understand from it that in his "Palkuriki Somanadhudeppativadu?" Sri Velaturi Venkataramanayya clearly established the poet's dates as 1180-1240. pic.twitter.com/gP5hwN2kew

— Bṛhasvāk बृहस्वाक् బృహస్వాక్కు (@BRIHASVAK) May 16, 2022

Mention of Yakshagana in Aandhra can be found in the Bhimeshvara Puranamu of Srinaatha. In it, it is described in tandem with Palkuriki Somanatha. Dance itself has a very old provenance in India. Though dates vary based on discrepancies between Indic and Western chronology, the latter aligns with the following:

“Panini has mentioned about two works on the natasutra, one by Shilaali and the other by Krishaashva, which undoubtedly prove that the practice of dancing was prevalent during Paanini’s time in the 5th century B.C. Patanjali has mentioned about the art of dancing the Mahabhasya, in connection with the stage (rangamancha) and dramatic plays (abhinaya). In the Ramayana (440 B.C.), the Mahabharata and the Harivamsha (300=200 B.C.), the practice of classical dances was current. At the court of Pushya mitra (150 B.C.) , there was a separate auditorium (Prekshagriha) as well as a separate music-hall (sangitashala) for the practice of singing and dancing.” [3, 63]

“the term ‘mudra’ which is used in the art of dancing (‘nartana-kalaa’), is derived from the root muda, which means ‘aanandam’ or joy: ‘mudam aanandam raati dadaati’”. From this it is understood that the word mudra, that is used in the art of dancing, is the cause or origin of joy and pleasure which are out-come of pleasing aesthetic sentiment (rasa) and mood (bhaava).” [3, 66]

From Maarga, one moves to Desi (often called the Desi course of Maarga). This refers to the classical tradition in regional rendition. Perhaps the most famous text on regional dance was the tome by the Chief of the Elephant Corps in the Kakatiya Empire: Nrtta Ratnavali of Jaya Senapati.

“The Inscription of Recarla Nami Reddi and that at Dharmavaram of the time of King Ganapati, recorded the names of Temple musicians and dancers. Dr. Raghavan says that the great gamut of the arts of music and dance in the Kakatiya times proves the valuable treasure. The Nrittaratnavali produced under king Ganapati and the text of the treatise was written by the Kings’ elephant-commander, Jaya-senapati in 1253-54 A.D.

The fifth chapter of that treatise contains a commentary treatise on pure music, called Gitaratnavali. The [Rana] Kumbha of Mewar consulted this Gitaratnavali while writing his monumental work Sangita-mimansa. The arts of music and dance of the Kakatiya period have also been depicted in the Ramappa Temple and the monuments. It is said that the Telugu Saivite writer Palkuriki Somanath borrowed many materials of music from the Gitaratnavali, and described numerous ragas, 7 kinds of aalaapa (elaboration of raga-forms), 22 gamakas, 108 talas (time beats and 19 methods of veena-playing.”[4, 73]

This is the classical history and the pedigree of the folk dance of Andhra, but what are the characteristics of the latter?

Characteristics

“Classical dances are designed by the elite and sophisticated dance teachers, and codified in manuals. Bharata’s Natya Sastra, the compendious work on Indian theatre, recognises regional dance styles. Bharata cautions the troupe to cater to the audiences of particular places, only such styles as they are familiar with. All this proves that folk dancers are not only traditional but also ancient.” [7, 116]

As such, there is a clear and intrinsic connection between the Classical Tradition and Folk Dance in India. Rather than 1-stilted size fitting all, Bharata Muni himself exhorts dancers to acclimate to their locale and accommodate local tastes. This naturally creates the need for a simple folk dance tradition outright.

“In the Dance in India, Faubion Bowers says:

‘…there are the ubiquitous folk dances of the villages and countryside which are still performed for amusement on special occasions in the streets and the homes. The aboriginal types of folk dances are generally vestigial ceremonial dances confined, for the most part, to the numerous aborigines, hill tribes, gypsies and depressed classes in the remoter areas of the Indian interior. “. [7, 116]

Given this variety and demography, nrthya was then adjusted to the needs of the janapaadha janaah.

“What are the things that strike one when a folk dance is witnessed? There are the naturalness, spontaneity and plas-tic movements of the limbs. A free and unrestricted flow of thought seems to pervade the physical movements. All feel-ings in the gamut from joy to sorrow are manifest. Though there seems to be conscious effort, it is overcome by unforced naturalness. For the spectator it seems to be an art form, but to the dance it is a ritual, performed with devotion. It took them some time to develop into professional dancers and singers.” [7, 116]

Varieties

North and South India are often simplistically seen in hermetically-sealed silos. This is because it has long been convenient for outsiders to utilise and appropriate the North (more exposed to invasions) via syncretism, rather than recognise the holistic connection and identity of North and South as ancestrally 1 ethnicity originating in the Indus Valley. There are undoubtedly changes today, and new ethnicities have arrived, contributed, and even modified the genetic makeup of various regions. But this does not belie the common origins of both regions. Just as Maharana Kumbha of Rajasthan made reference to Trilinga desa’s Jayasenapati, so too did Aandhra receive from Rajasthan.

The Lambadi Dance is connected to the Lambadi people of Rajasthan. This semi-nomadic tribe is also known as Banjara or Sugali, and is is found throughout the Telugu States today (as the eponymous Banjara Hills can attest. Dasara, Deepavali, and Holi are the special festivals of the Lambadis. “The Lambadi dances are simple but charming, and are inspired by the movements associated with daily tasks like harvesting, planting, sowing, and so on. The costumes, embroidered with glass-beads and shining discs, are picturesque, matched by the abundance of ornate jewellery worn by them. The jingling brass anklets, the hang-ing cowerey bunches and the ivory bangles from wrists to elbows, provide a natural rhythm to their dances.” [7, 122]

Kolaatam is one of the famed folk dances of Andhra. It gains its name from Kola (stick) and Aata (meaning play). It is also known as Hallisaka and Dhandarasaka in Sanskrit. [7, 128] But as above, culture is often exchange and interchange. True to the suspicions of many Telugus themselves, it is in fact traced to Dhaandiya-Raas of Gujarat fame. In Raghunatha Naayaka’s Sringaara Saavithri “he refers to Gujarati Melikopu which is but a Kolaata dance of Gujarat…must have been the Raasanritya which the Gujarati women were fond of.” [5, 129]

“Jayapasenani describes this Danda Raasaka in which there might be any number of women from eight to sixty four de-pending on the convenience of the leader. They will have to d[i]vide themselves into pairs holding two sticks in each hand. Each stick would be one and a half foot long, the thickness not exceeding the thickness of a thumb and well smoothened. This arrangement of sticks changes from region to region.” [5, 129]

A special type of this dance is called Jada Kolatam or Veni Kolatam, which is popular in Karnataka. A companion dance of Kolaatam is Chiratala Bhajana. Though it resembles its companion, it differs in key ways. While Kolaatam features 1 stick in each hand, Chiratala Bhajana features 2 sticks in 1 hand accompanied by 1 kerchief in the other. A troupe is made up of 10 to 20 members. They stand in a circle with a leader in the centre. The initial portion is literally Aadhi Adugu (first step), followed by Potu Adugu, Kuppadugu, Kulukula Adugu, Joku Adugu Nemili Adugu, Gurrapu Adugu, Uyyala Adugu, etc. Like many other dances, they have dancing brass anklets as well as colourful waistbands and floral garlands.

Predictably, one more dance ostensibly accompanied these Gujarati exiles, the famous Garba.: “The word Ghurjara has become Gujjari. Ghurjara means Gujarat. During the reign of Nayaka kings the Gujaraati dance had come to be known as Gujjari. ‘Garbha’ is a form of dance peculiar to Gujarati women. The Telugu speaking people call it ‘Gobbi Nrityam’, women stand in a circle, go around clapping and singing. There would also be some foot work.” [5, 143]

Among dances with a clear tribal connection is the kundali dance, often written as Gondali/Gondli. “It is said that once in Kalyanakatakam, the capital of the Western Chalukyas a tribal (Bhill) women had performed this dance. The ruler Someswara systemized this dance in accordance with the principles of dance and called it Godili nritya.” [5, 135]

A related dance (or perhaps even synonymous) is the Gusadi dance also of the Gonds. It is part of Deepavali( the harvest festival) of the Raj Gonds of Telangana. Attired in colourful costumes, troupes are made up of 20 to 40 dancers. They perform starting from the full moon day to the fourteenth day (Deepavali). Adorned with turbans of peacock feathers and horns of deer, they rhythmically gyrate to the dappu (tambourine), tudumu (tom-tom drum), and the pipri (trumpet). [7, 117]

Then there is the Dimsa Dance of the Araku Valley (Uttarandhra) Tribals.

“The Araku valley is the most charming hilly region in Visakhapatnam district. Valmiki, Bagata, Khond and Kotia tribes inhabit this valley and other agency areas of this district.” [7, 117] The archetypal dance of this confederation of tribes is the Dhimsa. Participants include young and old, male and female alike, during the month of Chaitra (March/April). Performed on weddings and community feasts, performers are called Sakidi Kelbar. These dances provide both entertainment and community solidarity and unity (so often lacking among modern Hindus).[7, 117]

There are 8 forms of this dance: 1) Boda Dimsa: worship dance for the village goddess, 2) Gunderi Dimsa, a male invites a female dancer to dance with him, 3) Goddi Beta Dimsa, where dancers bow and lift their heads in simultaneity. 4) Potar Tola Dimsa, which symbolises the picking of leaves while dancing in rows, 5) Bhag Dimsa, which has the practical purpose of instructing on tiger attack avoidance, 6) Natikari Dimsa, a solo dance of the Valmikis, 7) Kunda dimsa, where dancers push each other in-sync on the shoulders, and 8) Baya Dimsa, which is the dance of the tribal magician (ganachari), which features the dancers possession by the village goddess. [1, 117]

Next is the Siddi Dance. Of African origin, the Siddis of Ethiopia spread throughout India, rising to power in Maharashtra and even briefly (and indirectly) in Delhi. Located in part today around Hyderabad/Golkonda, they maintain their own tribal war dances of their ancestral homeland. Some are even found in rural Aandhra. [1, 122]

“Tappeta gundlu is a folk dance confined to the coastal dis-tricts of Srikakulam, Vijayanagaram and Visakhapatnam. This was originally performed by cowherds and shepherds as a ritualistic dance while propitiating the rain god and their favourite deity Gangamma. However, it has become popular among industrial and agricultural labourers of that area belonging to different castes.” [7, 123] They sing paens to Sri Krishna, Dasavataras and Gangamma via various folk songs. The Tappeta itself is a small percussive instrument. 8-16 artistes dance in a circle, beating the drums that they have tied to their chests.

“This dance requires skill as well as muscle power, only sturdy and able-bodied artistes constitute the dance troupe. The artistes exhibit rare skills in acrobatics while dancing…Their repertoire consists of twenty to thirty gatibhedas…Alll dancers sing pallavi of a song or a narrative following their troupe leader. While dancing the artists, eight in a group, stand one above the other on the thighs and shoulders in the shape of a gopuram (temple tower) or a tree with its branches hanging.” [7, 123] Hanging on each other, they whirl fast and fall on the ground with a thud. Many of their movements on the ground dance are similar to that of Punjab’s Bhangra. [7, 124]

Moving on is another dance associated with pots. “This is a group dance. Ghatakundali is one of its forms, the other being’ Valayaakaara Kundali’. In Ghata Kundali pots are arranted to suit the actions in the dance play. The artistes dance on them. The pots should not break under the impact of the foot work of the dancers. The dancers should not get off the pots. This requires the utmost skill of the dancers.’ Valyaakaara Kundali’ requires the dancers to form a circle. They take up some lyric or other to support their music and dance. Either a single posture or some changing postures form the highlight of their gyration.” [5, 135]

True to its name in Telugu, Urumulu is the Thunder dance. Performed only in Anantapuram, the vaadhya utilised is also called Urumu, and made from 2.5 feet of bell metal, covered in goat-skin. The dancers are scheduled caste (dalit). “They are a pious and virtuous group of people who observe religious austerity and worship goddess Akkamma. They abstain from drinking and eating meat. They present urumu dance to please their deity.” [7, 124] Dancing in a circle, they are attired in long shirts and big turbans with beads or coins around their shoulders. They present quite a sight with faces smeared in turmeric, singing devotional songs whilst dancing. [7, 124]

Following this is another literal Shepherd dance, the Kuruba dance. Priests among Kuruba caste people are called Goravas. A Ganachari initiates them into the practice of the deity Srisaila Mallikarjuna, and later the deity Mailara. Putting on a Kambali (black coat made of wool) and a cap made of bearskin, they hold a damaru with the right hand and play the flute in the left. Dancing in a circle, they call themselves the faithful dogs of Mailara and drink Panchaamrtham (sugared milk) as prasaadha. It is a religious dance for special occasions.[7, 125]

Garaga, or vessel dance, is common throughout India, especially Karnataka and Tamil Nadu (where it is known as Karagam). Originally a dance among a category of village priests called Asadis, it has skyrocketed to popularity in Telangana as Bonalu. To the rhythm of the dapu drum, dancers dance whilst balancing the vessels on top of their heads.

Butta Bommalata is a dance that is very much in line with a previous topic: Tholu Bommalata. Butta Bommalaata is popular during festival gatherings, particularly Vinaayaka Chavithi. A troupe is made up of 10 members of which 4 play instruments, 4 operate the puppets, 1 narrates, and 1 leads. The puppets here do the dancing, though puppet operators may themselves join in. [7, 127]

Veera Naatyam is the heroic dance best embodied by Jaya Senapati. The Gaja Saadhanika or Chief of Elephant Corps is himself reputed to have disembarked from his mount and danced the furious Veera Naatyam to inspire his troops to victory. “Viranatyam also known as Virabhadranatyam is a continuity of the traditional ceremonial dance presented in the Siva and Virabhadra temples when Virasaivism was at its zenith. Veerabhadra the destroyer of Daksha’s sacrifice is to be the originator of this dance. Holding a sword in one hand a shield in other hand the devotee dances and plays steps according to the beat of viranam, a big percussion instrument which, produces sharp and piercing sounds. Viranam sounds resemble the sounds of war drums.” [7, 127]

Artistes recite khadgas (sword poems) while wielding these eponymous weapons along with tridents and burning torches. The Viramushti, Jangam, and Devanga communities along with the Kalavanthula (Bhogam) community, preserve this dance to this day. Patayam of Travancore is said to resemble this Aandhra dance. [7, 128]

It is often thought that folk arts were condescendingly ignored by royal courts. But nothing could be further from the truth. One folk dance receiving Royal patronage was mentioned by the Brhath Desi of Matanga Muni (himself of untouchable/dalit background). “’Bruhatdesi’ described Jakkini as a dance form in which both lyric and action are equally important. The Yakshagaanas of the Nayaka times prove that Jakkini was often patronized in royal courts. Telugu literature makes us believe that Jakkini was popular in the Andhra country.” [5, 136]

Kanduka Kreeda is another dance that was once popular among the common people of Andhra. “Literally it means the ‘Ball play’. This has been in vogue in the Telugu speaking area times from ancient according to the references made to Kanduka Nrityam by Yerrana in that part of ‘Aranya Parva’ of Mahabharata, which he had translated. Jayapasenani had described this as the play of women who form themselves in the shape of a lake with lotuses. Balls made of gold, Silver, brass and wood and also balls with smaller balls inside them are thrown at each other or away from each other while each of the dancers move about according to vari-ous dance patters, being well orchestrated.” [5, 143]

Another folk dance that dazzles the popular imagination is the Puli Vesham or Tiger dance. It is a 1 man dance form that is attached to the Dasara festival. True to the name, the whole body of the performer is painted orange with black stripes. It is an energetic and animalistic dance that shows the power of the performer and the festival itself. [7, 132] On a zoologically-related nrthya note is the Horse dance, Gurram nrthya, popular in Guntur. Horse puppets made from straw and hay are coloured, with dancers serving as the riders. Tinkling bells are then attached.

Chindu may take a different meaning in today’s Indian civic dialogue, but unlike the former, this dance of Aandhra is wholly authentic. “Cindu dance is very common in rural Andhra during fes-tivities like Poleramma and Ankalamma Jataras to annual pro-pitiation of village deities.” Both genders danced accompanied by Tappeta, Cymbals, and Drums. [5, 144]

Here is a listing of other instruments that might be accompanied by the various dance forms:

“Tammata, Tappeta, Candravalyam, Mridangam, Maddela, Murajam, Dolika, Naagarajam, Bheri, Davina, Tamuku, Dakka, Avajam, Muduku, Damaruka, Ciruta-Maddela, Jarjhara, Gomukham are the leather instruments which were popular during the period of Nayaka kings.” [5, 167]

Last, but certainly not least is the Karuva dance of East Godavari district. It is said to be akin to the Rasleela dances of North India or the Karshani dance of classical treatises. The dancers are attired in the manner of gopis and gopikas, with Radha Krishna at the centre. The performance is conducted in Chaturasara, Thrisra and Misra gathis (tempos). [7, 133]

To summarise, here is a somewhat comprehensive (though not all-inclusive) list of dances popular among the common folk and tribals of the Aandhra region.

Folk Dances

- Kolatam

- Chiratala Bhajana

- Tappeta Gundlu

- Ghatakundali

- Urumulu

- Kuruba

- Garaga/Bonaalu

- Veera Natyam

- Kanduka Kreeda

- Puli Vesham

- Chindu

- Karuva

Tribal Dances

- Lambaadi

- Gondali

- Dhimsa

- Siddi

- Araku

Future

There remains today in Aandhra in particular and India in general, a galaxy of folk and tribal dances. Jaanapaadheeya Nrthya is here to stay, but continues to lack in patronage, as do so many arts and crafts in the Telugu states. Without popular interest in culture, the populace soon loses its culture.

From Puli Vesham and Dhimsa to Kanduka Kreeda and Kolaatam, Folk Dance in Aandhra runs the gamut. Today, Telangana must be credited for re-popularising Bonalu & Bathukamma, but the road remains long to reviving all the traditional dance forms of the Telugu states.

The future of folk dance, for the foreseeable future, seems to be linked with Telugu society’s film craze. With the world acclaim of RRR, TFI’s hold on Telugus will not likely diminish, and thus, should instead be utilised for the benefit of culture. Not only folk but tribal dances have often received homages, in films both of today and of yester-year.

After all, “mana mass-ollu ki, koncham beat-u aa oopu…”

References:

- Lath, Mukund & Ed. Kapila Vatsyayan. Dattilam. Delhi: IGNCA.1988

- Iyer, A.S. Panchapakesa. Karnataka Sangeeta Sastra: Theory of Carnatic Music. Chennai: Ganamrutha Prachuram.2008

- Prajnanananda, Swami. A History of Indian Music. Vol.1. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math. 1997

- Prajnananda, Swami. A History of Indian Music. Vol.2. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math. 1998

- Kusuma Bai, K. Music-Dance and Musical Instruments—During The Period of Nayakas (1673-1732). Varanasi: Chaukhambha. 2000

- Chaitanya Deva, B. Musical Instruments of India-Their History & Development. New Delhi. Munshiram Manoharlal. 2014

- Raju, B. Rama. Folklore of Andhra Pradesh. New Delhi: National Book Trust.2014.

Dance is the Geometry of LIFE.