History is not always epic kings clashing or empires rising and falling. It is also the story of a society and its times of penury and prosperity. Ironically, for a state so commercially oriented, Andhra Pradesh’s economic history is not discussed much in the public discourse. Indeed, the entire region was once 1 economic unit, as part of the wider Commercial System of Bhaarathavarsha.

As such, today’s article focuses on Andhra Economic History.

Introduction

Quite possibly one of India’s most materialistic societies, Modern Aandhra is a dichotomy of reality, with a patina of external spirituality. It has both high culture and deep culture in spades, yet is mired in materialistically crass pop culture. It has an ancient Imperial history, and yet has the attention span of a post-modern fruit fly. It knew unity in antiquity, but seeks only casteist divisiveness in posterity (caste anthems anyone?). For such a society to get a proper sense of itself again, one is perhaps best served by focusing on what they already do well: Economics.

United Andhra Pradesh was a dynamic state, with a technologically modern capital (Cyberabad) and an economically diversified and dynamic coast. Its mistake—as all parties attest—was in neglecting the dry interior of Telangana and not giving proper pride-of-place to traditional agronomy. The net result was agrarian stress and bifurcation (on specious grounds).

The hope of new Andhra Pradesh state is that a more inclusive approach to growth can take place, allowing dynamic entrepreneurs to prosper, whilst ensuring a dignified standard of living to labour and agrarian classes alike. With the return of Amaravati as its capital, the possibility again looms large. But to understand how to do that necessitates more than merely mimicking a mere city-state like Singapore. One must take a post-pandemic panoramic look at the entire Telugu region and understand its economic history and collective potential alike. To do so necessitates commencing with its economic components.

Economic Components

The essential economic components of any society begins with the Land and People. Land provides the resources and people provide the labour. Aandhra has land, labour, and entrepreneurship in dollops, but is externally dependent on capital (FDI) due to the idiosyncrasies of modern international finance. Dollars are lent externally then internally for governments and entrepreneurs to invest in public and private sector undertakings. Even poor agriculturalists of Aandhra (and other parts of India) who previous safeguarded and shared stocks of local seeds, are now debt-dependent on GMO-seeds all while international agro-corps breath down their necks with subsidised produce.

However, agriculture wasn’t always so complicated and externally dependent. It was once driven by local initiative and cooperatives rather than corporate finance and shareholders. True, it was dependent on the largesse of feudalists, rather than capitalists, but they weren’t always oppressive (the same can’t be said of the latter…).

“Kakatiya rulers of the 11th to the 13th century were exemplars of medieval south Indian kingship and models of appropriate ruler ship for chiefs of the peripheral zones. It was less the might of the Kakatiya rulers than it was their moral appropriateness that provided the basis of Kakatiya rule over the coastal plain.” [1, 49]

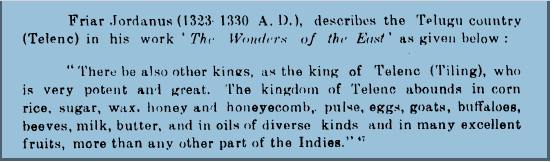

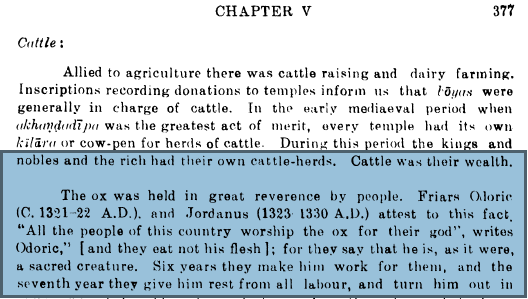

Agriculture

Ancient and medieval Aandhra was essentially agrarian. Though there was active commerce, and large scale fishing and mining, farming formed the bedrock of the Economy. Crops were typically adjusted to the climate/region. Being the land of erra matti dibbalu, Trilinga desa has red soil, black soil, and coastal alluvium. Moreover, it has thick jungle, dry plateau, and a lush coast. This was further informed by the tribal economic contribution, from communities such as the Boyas and Chenchus, who actively traded with their settled town and city brethren in the Telugu country. They practice small-scale agriculture of basic crops, whilst being active hunters of fowl and deer.

“Cloth products were a different matter. Records indicate that there was a considerable demand for south Indian clothes not only in Andhra Pradesh and south Indian hinterland but also in foreign lands. This demand was met by the development of a well-organised industry which appears to have been characterized by the specialization of th its various components.” [1, 72]

Agricultural surplus paves the path to town manufactury and artisanship. Local small industries (such as handlooms) provides accessible earnings and occupation to the medium-skilled populace.

“Weaving as an industry was systematically promoted by the rulers right from ancient to medieval times. The Chalukyas, the Kakatiyas and the post-Kakatiyan rulers – the Reddis, the Rayas of Vijaya Nagara period paid special attention on the old centres of textile production and also encouraged the settlement of weavers in new areas. The districts of Warangal, Guntur and Kurnool were major cotton producing regions of Andhra Pradesh as mentioned earlier.” [1, 73]

Other areas that received such patronage were Vinukonda and the great port city of Motupalli, which became prestige centres for textile production. [1, 73] However, most of these artisans were not necessarily self-employed. “In predominantly agrarian set up, the artisans were attached to the locality i.e., to the temple, to the landed brahmins [brahmadeyas], and kampulu (the landed gentry, i.e. kaapus) through interdependent land tenures.” [1. 72]

As time progressed, this changed. The fortunes and influence of the artisan guilds would transform. Soon, situated in nagarams, they would form nakarams to ply their trade and their wares: “the artisan community thus became more visible from the 10th century onwards and by the privileges, conferred upon them by the socially influenced groups which directed towards the improvement. The increased economic status of local artisan community members allowed them to demand and receive special treatment by agrarian assemblies of the hinterland. ” [1, 72]

This led to the rise of the Saliya nagaram, a puga which marketed textiles. Pugas were village business concerns (or sometimes sell swords). Nigamas were the larger, more trans-geographical corporations. Srenis were associative guilds, typically organised around a particular handicraft (i.e. goldsmith guild, masonry guild, etc). The Aihole-500 are one of the most famous guilds in history, and another is the Teliki-1000: “we have references to the Telikis-1000 of Bezawada an organization of oil mongers which originated in the 11th century AD in [Medieval Andhra Pradesh] and became a supra-local trading organisation similar to that of Vaniya nagaram of Tamil Nadu which came into existence around 10th century AD. The Telikis-1000 of Bezawada spread out by entering into inter regional commercial network acquiring a viable economic status by the 12th and 13th centuries so as to be included in important decision making process involving the merchant community and the name itself indicates that they were divided or organized into 1000 families such as , Velumanulu, Pattipalli, Nariyallu, Kumudallu, Marullu, Povandlu, Srvakulu, Undrullu, Anumagondalu, Addanullu, etc. and organized their commercial activities by maintaining close relations with itinerant merchants that is Nanadesis and Veera balanjyas.” [1, 75]

” The artisan classes of the Visvakarma community formed main industrial community and were organized into a guild of their own. Of these artisan community, it is only the five classes of people, worked in metal are popularly known as ‘Pancanamuvaru’ – the goldsmiths, blacksmiths, the carpenter, the mason, and the brazier. These claimed their [descent] from the five sons of Visvakarma, and hence their community is known as Visvakarmakula.” [1, 73]

“They traced their lineage to Visvakarma (Sri Visvakarma vamsodhbhavulu). They claimed to have been the descendants of the five sons of Visvakarma named Manu, Maya, Tvastram, SIlpi and Visvajna. The originators of the crafts, thus, the Pancanamuvaru in the families of Visvakarma and were divided among themselves into five sub-divisions of the artisan community.” [1, 121]

Aveshana (artisanship) was typically divided into karukarma (handicrafts) and charukarma (performative crafts, i.e. dance, song). Along with occupation as servants, the fourth varna could find gainful employ in these self-employed capacities as well as regular soldiers. The Veera balanjyas would combine the two to make their way into landed gentry (lower aristocracy), and make their mark in the late medieval period.

Nevertheless, industry was not limited to artisanship. There were other gainful endeavours that would fill the public coffers.

“The third major industry in this period is the manufacturing of salt. The salt manufacturing centres generally are located near the coastal towns along east coast from the Pulicat lake in the south to Kalingapatnam in the north and Peda Ganjam Pina Ganjam, Kadakuduru, Kuraveda, Perati, Uppunganduru, Payundorrum Upparatla in Guntur district were some of the most important salt manufacturing centres.” [1, 76]

Finally, mining was another crucial enterprise, that was typically in the state’s hands. Aandhra was famous for its kollur diamond mine. Precious stones and pearls (muthyaalu) would be sold at commercial ports.”These itinerant trade organizations were involved in the administration of commercial activities in the Andhra Pradesh ports and also assumed administrative control over major trade emporia of the hinterland which ere designated as Balanja pattanam.” [1, 141]

Indeed, merchants were not always stationary. Local merchants might dominate local trade, but itinerant merchants would serve as middlemen to national and international customers.”Inscriptions of medieval Andhra Pradesh, particularly of ka[katiya] portrays Andhra Pradesh ports as being administered by royal officials who together with groups of itinerant merchants and local assemblies, controlled the activities of foreign merchants and their contacts with the indigenous commercial networks.” [1, 141]

Metro Industry & Commerce

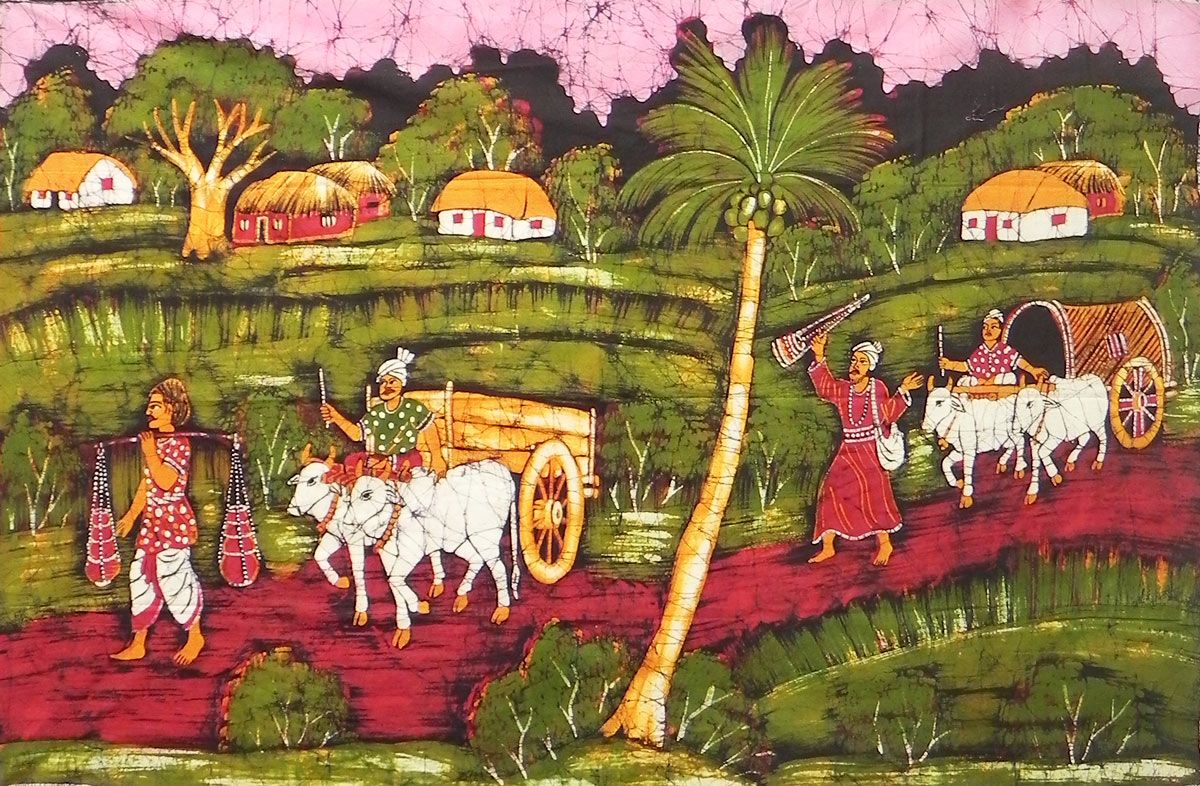

Ports were an essential component of commerce back then as they are now. The Sanskrit word Pattana is the origin for the Telugu word for port: Patnam.

“From early times to the 15th century, the sea presented an opportunity for south Indians, particularly Andhras to trade with foreign countries. Foreign records identify Orugallu, Bezawada are inland trade centres as early as the second century B.C. and other important trade centres are Visakhapatnam,Machlipatnam, Krishnapatnam, Motupally and Kakinada as important entrepots.” [1, 48]

If the town and country were pre-dominated by the fourth varna artisans and mercantilists, then the cities were dominated by the Third Varna commercialists. The Aarya Vaisyas of Aandhra are colloquially known as Komatis. They have produced many great merchants and are known for both their wealth and vegetarian culture. The title setti is historically applied to them (coming from the Sanskrit: Sresthin→ Setth→Setti ; however, it is shared today with a peculiar merchant-warrior community as well, that will be discussed later.

Currency

Currency is an essential part of any economy. Short of barter (direct exchange of one good for another), money provides a medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value, and a mechanism of credit. Throughout history, precious metals (especially gold), served this function. This was attained primarily through coinage (rupaka) and money orders (hundika). Prior to the modern petro-dollar based system, the gold standard prevailed. Prior to that it was bi-metallism (gold & silver). In the case of India, tri-metallism (gold, silver, & copper) was the norm.

Another unique money form popular throughout the Indic world (even the Maldives) was the cowrie (kauri) shell. Nevertheless, gold coinage stood the test of time, the world over.

“Prataparudra in the Uttaresvara grant is stated to have made a gift of 100 nishas to the scholar Viddanacarya. Two inscriptions from Kolluru dated AD 1137 state in Sanskrit 5 nishkas and in Telugu 5 gadyas. In a Tripurantakam inscription, it is stated that 850 gadyanas and 150 gadyana madalu and the total amount being equated to sadyana one thousand madas. This and similar statements made it clear that nishka, mada and gadaya are synonymous…another record dated to AD 1293 from the same place mentions that pahini gadya indicating that the gadyas are gold coins. The next denomination is ruka. Ten rukas make one gadya or mada….Kesari-adduga occurs in one of the inscriptions found at Nadendla dated to AD 1258 and it is equal to half ruka. Padika is one fourth of a ruka and this kesari ruka has been found in several inscriptions of the Kakatiyas period.” [1, 221]

Credit

Credit is the sine qua non for large scale projects and even extended wars. It is the literal lubricant for any economic system. Money (whether in the form of coinage or paper currency) is often fleeting. In the absence of liquidity, credit mechanisms are required. Rather than modern banking, traditional guilds (sreni) and nigamas, along with local money-lenders, served this function.

“A local institution like nadu was quite capable of legally excluding itinerant merchants from markets by forbidding local merchants from transact[ing] business with them. In such a system, nagarams would have assumd a ‘banker’s role’, colelcting, storing and protecting local goods and utlizing them to conduct trade with itinerant merchants and other nagarams.” [1, 137]

Customs Duties

In this era of Free Trade Agreements and Economic Unions, it becomes difficult to imagine just how crucial customs duties and excise taxes once were to financing local governments. And yet, kupasulka excise on export-import (ekkumati-diggumati) was central to raising funds for public works. Bhaagamu was the 1/6th agro-produce tax and Ammubadi sunkamu was the sales tax (some things don’t change!). Angadi sunkamu was market/store tax, Illari was house/capitation tax, and sunkamu/ari was the general term for tax.

As if all this tax weren’t enough, there were tolls such as octroi and ferry cess (revu-sunkamu). There was also the famous (infamous?) vetti-chakiri (tax on labour), which originally began as the standard world practice of corvee, but became something else during the colonial era. These taxes were collected by a sunkari (tax collector) and theerpari (district collector). The ancient Aandhra Economy (and its medieval counterpart) relied on this to good effect.

The Abhaya Saasanam of Ganapati Deva reduced these customs duties to reasonable levels all while ensuring the tradeable goods of foreign merchants. This incentivised commerce and interchange all while enriching the kingdom of the Kakatis.

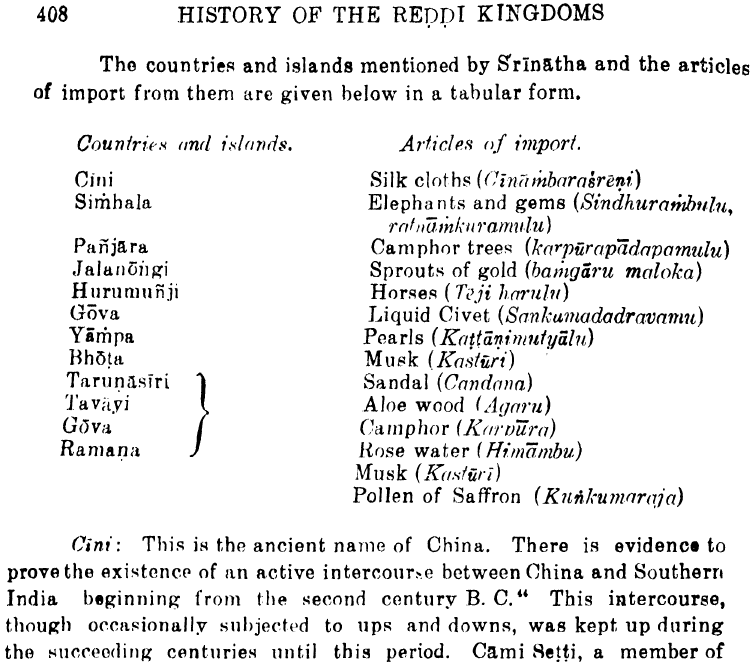

Exports & Imports

The trade balance of India in general and Aandhra in particular was historically positive. The plentiful Roman coins dating back to antiquity attest to the regional trade surplus. “By thirteenth century and impressionistic view of the guild inscriptions is that the volume of overseas imports in Andhra Pradesh had increased considerably.

Precious stones, pearls, aromatics, perfumes, myrobalans, wax, honey, some spices, some textiles including silk, horses and elephants were imported and the exports consisted of cotton textiles, iron, spices such as pepper, dyes, ivory, areca and putchuk. The items of export contained little in the way of preciosities. The textiles required technical skill for their manufacture. The iron was either an import or an export. If it was an import then may have been imported from east Africa which was later processed by unique methods in India and then used for the production of the famous Damascus sword.” [1, 252]

The various guilds of Aandhra (and Peninsular India) had various responsibilities as well as privileges.

“The Ainnurruvar, often styled the Five Hundred Svamis of Ayyavolepura (Aihole), were the most celebrated of the medieval South Indian merchant guilds. Like the great kings of the age, they had a prasasti of their own which recounted their traditions and achievements. They were the protectors of the Vira-Bananjudharma, i.e. the law of the noble merchants, Bananju being obviously derived from Sanskrit Vanija, merchant. This dharma was embodied in 500 vira-saasanas, edicts of heroes. They had the picture of a bull on their flag and were noted ‘throughout the world’ for their daring and enterprise. They claimed descent from the lines of Vasudeva, Khandali and Mulabhadra, and were followers of the creeds of Vishnu, Mahesvara and Jina.” [5, 300-301]

“Among the countries they visited were Chera, Chola, Pandya, Maleya, Magadha, Kausala, Saurashtra, Dhanushtra, Kurumba, Kambhoja, Gauda, Lata, Barvvara, Parasa (Persia), and Nepala…they filled the royal treasury with gold and jewels, and replenished the kings’ armoury; they bestowed gifts on pandiths and sages versed in the four samayas and six darsanas. There were among them the sixteen settis of the eight nads, who used asses and buffaloes as carriers, and many classes of merchants and soldiers, viz. gaveras, gatrigas, settis, settiguttas, ankakaras, biras, biravanijas, gandigas, gavundas, and gavundasvamis.” [5, 301]

The privileges included the right to collect tax (sunkamu) as well guild fees (panukulu). Artisan guilds, in return for collecting these taxes, would themselves be exempt. They had a code of conduct (samayachara, samayadharma) based on contracts (samaya). Itinerant merchant guilds (called nanadesi pekkandru) would trade their wares at angadi (permanent shops) throughout the region.

Andhra Economic History

“The Telugus were for a long time known as hardy marines. From an early period they navigated the seas and their bold sea-faring exploits carried them to distant parts of the world. In the far-off southeast Asian Archipelago, they met the equally ancient Chinese mariners who called them Kalingas [Kling], as the northern part of the Telugu area was then called Kalinga. ”

Further, the impressive maritime activities of the Calukyas, the Kakatiyas, and the Rayas of Vijayanagara were: but continuation of the earlier Satavahanas interest in overseas trade.” [1, 47]

Dating back at least as early as the Andhra Satavahana era, the Aandhra people have a storied story in maritime history. Under the great Gautamiputra, they were the Lords of the Eastern and Western Seas, and often ruled Sri Lanka, Andaman, and Parts of Myanmar and Malaysia (at least as suzerains). Merchants of many varieties and families came and crossed the Purva Samudra (Eastern Sea), in boats larger than their contemporaries in Europe and Asia.

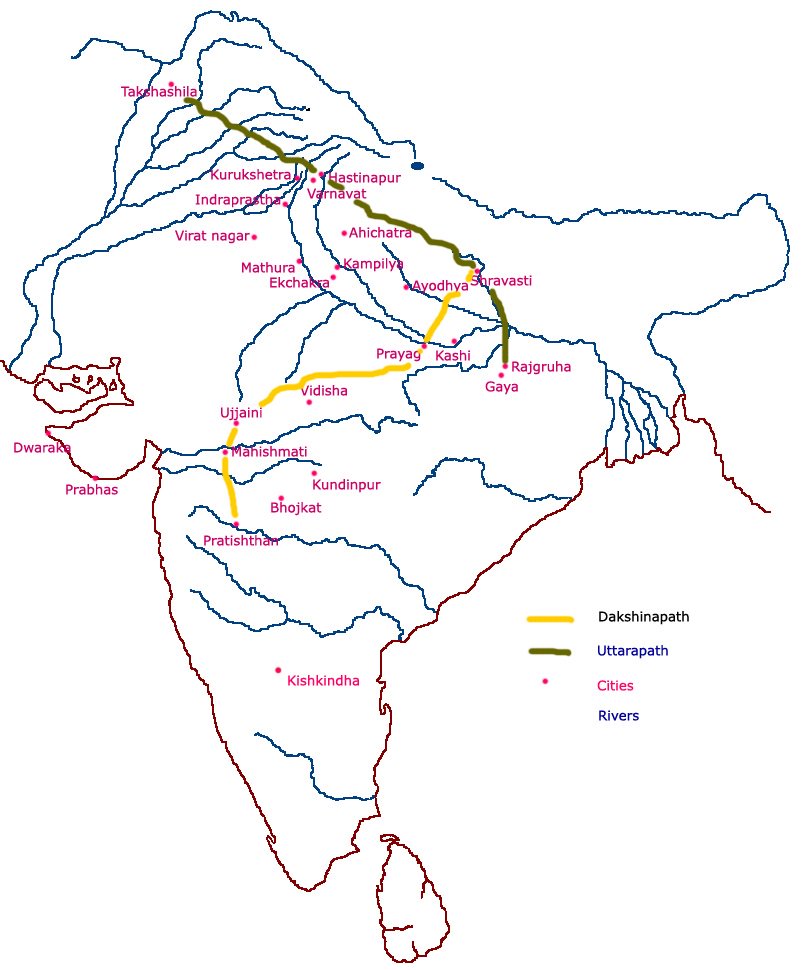

Aandhra was an essential part of the Dakshinapatha (Deccan is a modern misnomer). One of the historical five Indies, the North and South false dichotomy misrepresents the actual diversity of the Indian Subcontinent, which had Uttarapatha, Madhyadesa, Praachya (Eastern), and Pratheechya (Western) divisions.

“The Telugu poet Ketana of the thirteenth century indicates, in a verse in his Andhrabhaasabhoosanam, a treatise on grammar in Telugu verse, that the main route to Ayodhya from Kaanci passed through Nellore and Orugallu (Warangal).” [2, 390]

“Such corporate bodies or trading guilds have been a regular feature of Indian economic life from the time of the Andhra satavahanas” [2, 393] Telikis had 1000 families in their corporate body of oil-millers. Veera Balanjya corporation of traders and businessmen are prominent in inscriptions of this period. [2, 395]

Veera Balanjyas of Ayyavolu

The 500 Swamis of Ayyavolu were Veera Balanjyas, who are equated with the Balija Naidu section of the Kapu caste. Indian history is typically sandwiched between the anti-caste and casteist categories. Neither one has a proper grasp of the nature of proper Vedic society leave aside the validity of the modern arrangement, or even the terminology. For Jatiwadis out there, jaathi actually means race, and is a latter interpolation, violently and invalidly grafted, onto the the original Vedic system of Varnashrama Dharma. For this reason, in Telugu parlance, jaathi is actually referred to as kula (clan), which is much, much closer to the correct term samooha (community). In fact, what is erroneously referred to as “jati puranas” by some sections of kulagajjis, is in fact correctly called “kula puraanas” and sthala puranas (danda kavile/kaifiyat). [1, 22]

The Aandhra provinciality and Vaidikaarya ethnicity did not consist of separate races (jaathis) but multiple sub-ethnicities within the same race. The intrusion of other races/civilizations in the medieval and the colonial period does not change the historic reality of Bharatavarsha. Jaathi is merely yet another scam to divide and rule and disintegrate dharma (varnashrama or otherwise) by some sections appropriating none of the responsibilities but all of the privileges for their (foreign) “race”, i.e. jaathi.

Multiple communities (i.e. regional components) often exist within a varna. Typically, this is on the basis of desa/pradesa (country/province), which have immutable borders and refer to merely the land and people. Janapaadha, however, refers to a country as a mutable cultural-political unit (as used in English today). Modern India today is both janapaadha (country) and raashtra (political state/polity), with multiple pradesas/uparaashtras (provinces/states). The closest approximation to nation is in fact janatha, coming from the word, janaah (people).

“In early medieval times land grants and subinfeudation led to on equal distribution of land and power or a large scale and created new social groups and ranks indirectly and which did not quite fit in with the existing four fold social order. Social change was modified not only by the rise of various strata of landed gentry connected with administration but also by the change in the relative position of the vaishyas and sudras.” [1, 77]

This is seen in not only the transformation of the veera balanjya community into an oceanic enterprise, but also in the various artisan castes that formed their own guilds, whether as weavers (padmasalis) or toddy tappers (gouds).

“Thus, the attitude and ambition of artisan class is reflected in the medieval Telugu literature in the form of caste myths (kula puranas). Almost every important community like the weavers and artisan classes, oil pressers, etc., had this kind of eulogies (prasastis) recorded in the contemporary inscriptions.” [1, 77]

“It may, however, be noted that all artisans or craftsmen were not dependent, many of them worked independently.” [1, 79]

An interesting point of order is that according to varnashrama dharma, the vaisya caste actually had both trade and agriculture as its original occupation set.

“The traditional concept of regular and lawful means of livelihood for vaishyas, consisting of trade (vanik), agriculture (krsa) and cattle rearing (pasu palayam) continued to linger even during the early medieval period.” [1, 78]

What was permitted to one samooha or varna might not be acceptable to another in times of distress and calamity.

“In fact, the concept of apadharm which allowed to force the people of higher or lower castes (varnas) to take up trade in times of distress, made them (mercantile communities) as class in which the cult of wealth cut across the concept of caste.” [1, 80] “In the Pehoa inscription dated to the 9th century AD in the western India mentions that a brahmin called Vemuka as dealing in horses though Manu prohibits the sale of animals by a brahmin.” [1, 80] “Vignaneswara, commenting on Yagnavalkya quotes Devala to show that a sudra could engage himself in sale and purchase of all commodities.” [1, 81]

Aside from local retailers, there were also large-scale itinerant merchants.

“In the sources of the period, we come across a large number of professional and functional designations of merchants. The most common being sresthi, setti settikara, mahajana, banika, etc., which were used for merchants and magnets…In other words, the sresthis or settis were probably the wholesale dealers i.e., a class of middlemen between the producers and the retailers, who supplied liquid capital on interest to the needy merchants and farmers.” [1, 83]

“The most important communities the pill[a]rs of the whole network, however, were the Vaishyas of Penugonda, the Viswa Karmas or Pancanamuvaru (five castes) the Telikas 1000 of Bezawada, the Virabaalnjas of Nanadesi, etc.” [1, 84]

Nevertheless, the 500 Svaamis of Ayyavolu are famed in the history of peninsular India for their commercial prowess.

“The founding of the Aihole-500 in the 8th century AD may be attributed to a decisions of the 500 ‘Mahajanas’ of Mahagrama of Aihole, to provide an institutional base for the commerce of Karnataka region. Its organization and its activities were later expanded to other parts of South India namely Tamilnadu and Andhra Pradesh where the itinerant merchants of Aihole-500 was style as ainnurruvaru and balanjas in the 9th and 10th centuries respectively.” [1, 88]

However, these were not your standard ‘banias’. They protected their wares with sword and shield.

“Being the longest itinerant merchant organization carrying distant regions and divergent commercial areas, the Aihole-500 was the only organization to have mercenaries to protect goods and to set up protected merchant towns (with warehouses) called balanja pattanas (erivira pattanans in Tamilnadu). The Samayasena seems to have been mentioned in Telugu inscriptions from the second half of twelfth century A.D. The Basinkonda inscription in Chittoor district dated to 1128 AD mentions that the ubhaya-nana desis maintained regiments of foot soldiers and swordsmen as samaya balas. This army of the guild was known as Samayasena and its head as Samayasenani” [1, 97]. “The Bapatla record dated 1148 AD states that a certain Kamisetti was the Senapati of the guild, called Gangeyarayasamaya, a chief of Velandu. The army of the guild either local or feudal was named after the king. This indicates that there were close relations between ruling part and Ubhayanana desis or guilds” [1, 98].

Veera Balanjyas have inscriptions associating them with the Svaamis of Ayyavolu.

This in turn helps us understand not only the Veera Balanjyas, but also the old united Aandhra desa as a well-defined land entity and people. It was a veritable corporate nigama.

“as the Veera Balanjya corporation was the sole Trade Union which spread its activities over the whole of South India, Ceylon, and some countries and islands in the East, its records are found outside the Andhra country also” [2, 396]

“In some of the Canarese inscriptions of the twelfth century, they are said to have been Bananjigas (Vanajigas) ‘the brave of the brave, protectors of the submissive, cruel to the wicked, good to the good, and conquerors of powerful enemies’. In this inscriptions their warlike spirit is well described”[2, 396. see also chintapalli inscription]”

Regarding the Svaamis of Ayyavolu: “A perusal of these records shows that they had also a prasasti, not a whit different from but completely identical with, that of the Veera Balanjyas. The Ayyavoles, or lords of Ayyavalipura, also claim to have been the protectors of the Veera Balanjya dharma, to have obtained pancasata veerasaasanas, evidently the same as those claimed by the Veera Balanjya union, and to have immigrated from Ahicchatrapura to Ayyavali, the modern town of Aihole, in the Hangunda talik, Bijapur district” [2, 397] “they had 32 sea ports, eighteen cities”, [2, 398]

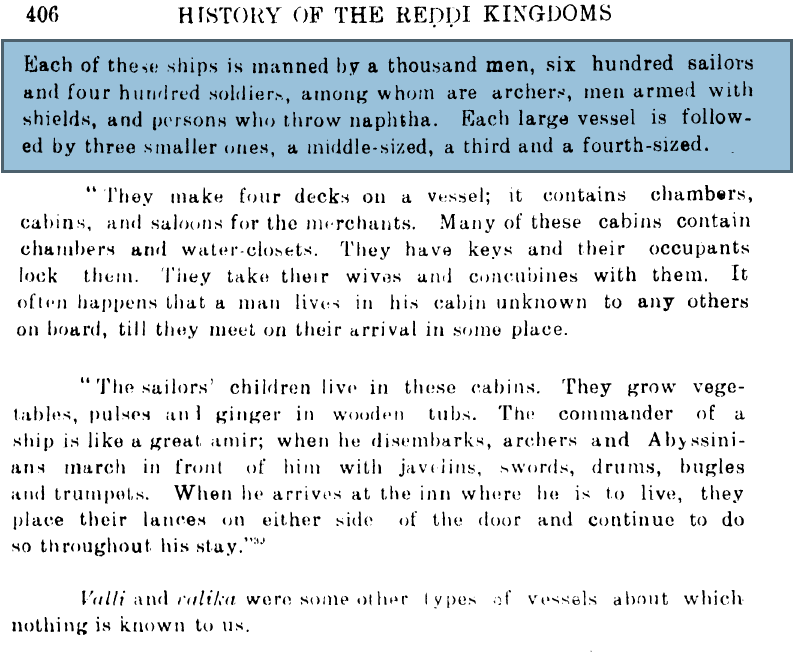

Nicolo Conti: “They (they natives of India) build some ships larger than ours, capable of containing two thousands butts, and with five sails and as many masts. The lower part is constructed with triple planks in order to withstand the force of the tempests to which they are much exposed. But some ships are so built in compartments, that, should one part be scattered, the other portion remaining… accomplish the voyage” [2, 405]

“Duarte Barbosa states, “they (the foot-soliders) carry strong round shields covered with silk. Everyman carries two swords, a dagger, and a Turkish bow with very good arrows; others carry steel maces. Many of them wear coats of mail and other jackets quilted with cotton….”’Their bows are long like those of England” [2, 239]

Kaijeetagaandru were levy troops raised temporarily for campaign. But they were known for their bravery as they were members of the mercantile unions. “The valanjiyaar and the Nagarattaar seem to have been identical with the Veera Balanjyas and the Nagaras mentioned in the epigraphical records found in the telugu country.” [2, 242]

Ekkati were the reserve army. They were a separate military caste called vantarlu (ontaru). They were proficient in heavy weapons like the mace.

“The traditional list of weapons of the hindus consists of thirty two weapons. These include swords, sabres, daggers, maces, javelins, spears, battle-axes, discs and so on. Besides these there were artillery engines to discharge stones (paasaana yantras or catapults). [2, 241]

Nakaramu

Another popular form of guild was the nakaramu. Based around the nagaram (or commercial city), they were (at least initially) predominated by the vaisya (komati) community. One example was the Visakhapatnam Nakaram 12. This consisted of 12 major merchants. Another was the Penukonda-18 (made up of 18 satellite towns of the famous Vijayanagara capital). [1, 106] These nakaramus would typically focus around a main product (i.e. saliya nakaramu for textile, telika nakaramu for oil pressing, and so on).

Many of these guilds would rise to such prominence that they were also entrusted with temple construction and management. Contrary to the modern free temples movement, it was not the priests, pandiths or braahmanas in general who managed major devalayas. Large public temples were managed by government administrators under the devayathana adhyaksha, and large private temples were run by charitable merchants or guildsmen. [1, 109]

Conclusion

“The Tamil records mentioned the Telugu as ‘Vadugars’ (the Northerners) and the Pallava kings of the 6th century called the land ‘Andhrapatha’. The indigenous name ‘Tillinga’ (Teleng or Telugu) came into vogue as the name of the language and gradually the terms Andhra and Telugu became synonymous, designating the land, the language and the people of the area.” [1, 56]

“Andhra Pradesh is the homeland of the Telugu people, who are also known as Andhras.” [1, 32] This United Andhra Pradesh was “divided into three geographical zone – Telangana, Rayalasima and Coastal region” [1, 32]. Hence reference to new AP state as “Andhra” is inaccurate, as Aandhra referred to the historical Telugu speaking regions including Kosta (a.k.a Coastal Aandhra).

Obscurantism, obstructionism, pedantry, and solipsism, this is what rules the day today. There is no attempt to understand extenuating/beneficent circumstances. The leader is either a great genius (avathaar!!) or utterly stupid and worthless. People either open their mouths when they shouldn’t, or don’t open them at all when they should. Etiquette, moderation, calm and collective thinking don’t exist—unless there is a scam to run of course. Profit primum est!

Perhaps no part of the developing world is more completely consumerist not only in mindset but in cultural programming itself. Bhaaratheeyas in general and Aandhras in particular need to de-programme from this stubborn consumerist idiocy, and re-culture themselves in what is of greatest benefit to their own society. All the corporate social responsibility marketing and high-minded corporate missions and values don’t change the reality that the people themselves have become greedy fools at all levels. Some camouflage this in caste and others camouflage this in anti-caste, but the scam is always the same—after all, politicians ultimately reflect their own people. It is the people who must change—or soon they will find that the world political situation will demand that they do.

Wealth is indeed possible for those who wish to work both industriously and honestly. Investing in one’s own community, rather than seeking instant returns from phoren needs to become the credo of the hour. Local handlooms, lepakshi handicrafts, and state self-respect mean that people begin to value what is genuinely theirs, before seeking to buy from outsiders. Value what is yours, invest in what is yours, and then sell the surplus. That is the honest way to wealth, and the crux of Ancient Aandhra Economic History.

References:

- Rao, T.Dayakar. Trade and State Craft in Medieval Andhra: A Reappraisal (600-1600 AD).Delhi: B.R. Publishing. 2016

- M.Somasekhara Sarma. History of the Reddi Kingdoms.Delhi:Facsimile Publ. 2015

- Rao, P.R. History and Culture of Andhra Pradesh. New Delhi. Sterling Publishers. 1994

- Modali, Nagabhushana Sarma, Ed. Mudigonda Veerabhadra Sastry. History and Culture of the Andhras. Hyderabad: Telugu University. 1995

- Sastri, K.A.Nilakantha. A History of South India. New Delhi: Oxford. 2015

[Article Updated on August 26th, 2024, due to online origin disputes about Aihole 500]