Introduction

There has long been some controversy around the existence of Kshathriyas in the South. There is blame on all 3 sides. The british naturally sought to divide and separate North and South as much as possible, and limiting orthodoxy to the North via AIT was one way to do it—as well as diminish Southern challenges. Indeed, the british did everything they could to de-mobilise martial communities such as the Reddis & Kapus who produced polygar warrior-rebels such as Syeraa & Veerapandia, retaining only the demeaning named “Madras[i] Regiment”. The kalari-trained Nairs stand out for their preserved ancient warrior traditions. North Indian narcissism (driven mainly by Punjabi narcissism) is a reality that has to be addressed and seeks to deny any Southern spotlight (whether Satavahana, Rashtrakuta, or Bhonsle). The false claim that Rajputs were the only Kshathriyas is yet another example.

But there is also Southern parochialism, and a peculiar type of small-hearted myopia that the more wounded North doesn’t have. The net result is caste Olympics down to the granular level—most preposterous in Aandhra. Kerala doesn’t help matters by making claims that Nairs were Kshathriyas, which they were not. As a military/soldier caste they should certainly be esteemed for their achievements especially against the Dutch, but vague ceremonies aside, their kings were equivalents of the various Nayak/Gentry baron castes of other parts of the South (i.e. Vellalar/Mudaliar, etc). Karnataka, in order to secure its claim on Vijayanagara, insists the Yadava Sangamas were the Yadava-Golla-shepherd caste, when they were not, or refers to the brave Bunt/Shetty caste as Kshathriya (“Buntulu” means soldiers). Though the achievements of these warrior groups in medieval resistance and liberation are praiseworthy, their neo-political claims cannot be used to deprecate the actual ritual-royal Kshathriyas.

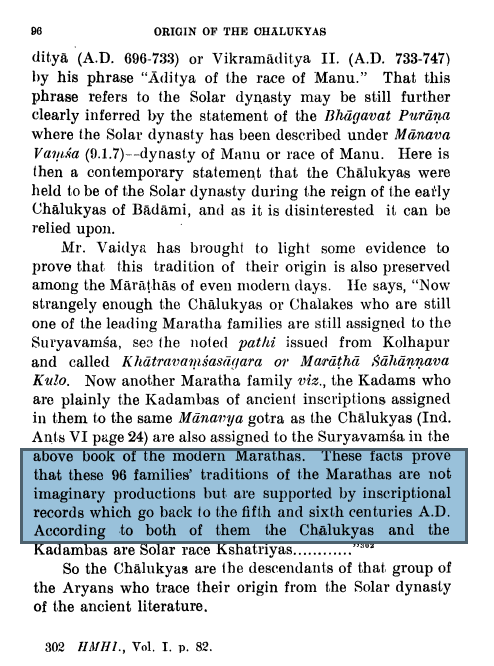

The truth is, ritual-status Kshathriyas did and do exist in the “South” (here I use it in the full Dakshinapatha sense). The 96K Maratha caste has it in their Kulin ranks, and the Aandhra Kshathriyas or Raaju caste certainly were and are as well. Due to invasions it mostly reduced in the rest of the South or merged with one of these two castes (as the Chola Arasar Tamils did with Raajus)—sporadic pockets of Deep South Rajput communities aside.

Conti, Razzak & Babur say Deva Raya II and KDR were by far most the powerful Hindu Kings in all India. Whether Kannada or Telugu, they were undeniably Kshathriyas. So what is the origin of Kshathriyas in Aandhra, well, here it is:

Prince Aandhra dates back to the Ramayana. This is because Romapada was a Kshatriya of the Lunar dynasty. He adopted the daughter of Dasaratha—her name was Saantha (married Rishi Rishyasringa). Romapada was a descendant of Usinara (7 generations removed). Usinara’s brother was Titiksu. 6 generations after Titiksu was prince Aandhra. Pandit Chelam asserts Aandhra and Dasaratha were contemporaries. Ramayana refers to Aarya Aandhras as well.[4, 139].

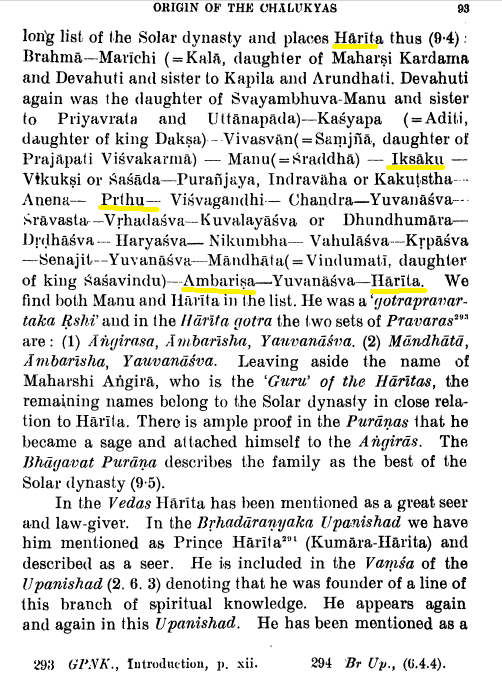

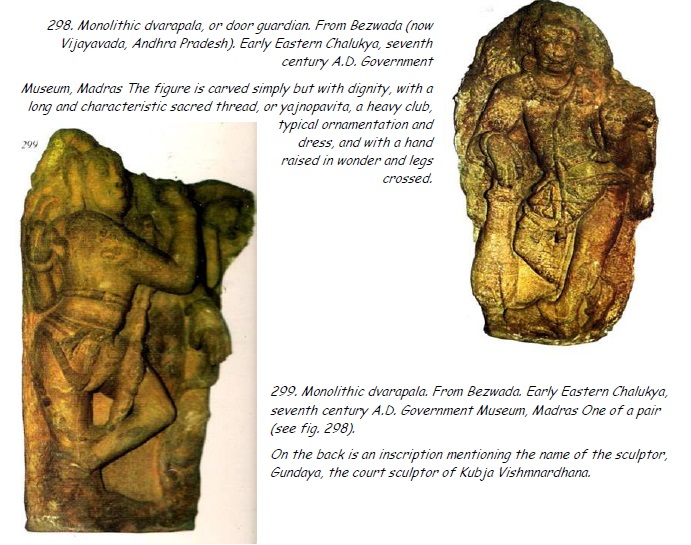

The Solar dynasty was also present, but the most prominent in our era was the Fire Dynasty or Agnivanshi. Contrary to british indologist fanbois, this fire ceremony wasn’t to induct Saakas as Kshathriyas. Rather, it was to induct Braahmanas as Kshathriyas, since Agni is the prime devatha of Braahmanas. It is here that the Chalukya vamsa (Chaalukya) stands out as 1 of the 4. The Eastern Chalukyas originated in Karnataka but through the rise of the Imperial Chalukyas of Karnataka under Pulakesin II, they captured and ruled Aandhra for a number of centuries. Though like many Rajputs in the North, their later branches would claim to be Chandra or Surya, they were, in truth, Agnivanshis. This is confirmed by the final Vijayanagara Dynasty of Araveedu, which is famously Agnivanshi as well.

The Dutch, Belgians, English, Germans, Swiss and to a lesser extent the French & Spanish, all have a common Teutonic ethnos that colours their classification as “White”. All these countries would be provinces under a united nation “Teutonia” just as Aandhra, Vanga, & Kasmeera are part of Bhaaratha today. The true old meaning of ethnos (nation) referred to related tribes that peopled a number of city-states or even countries. The Greeks were similar with Athens, Sparta and numerous coastal islands of Ionia as distinct states within the nation of Hellas, with Macedonia, Crete, Cyprus, and Chersonesos as distinct countries (not too much smaller than Laata or Chola desa of old) in Hellenistic civilization. And that is the point. Today we have conflated land-country desa (i.e. Aandhra) with people-country janapaadha/political state (Bhaaratha). Sovereignty ebbs-and-flows, but the common descent from common ancestors like Svayambhuva, Raama, and Bharatha, are what defines Bhaaratheeyas, and especially their Kingly castes.

Background

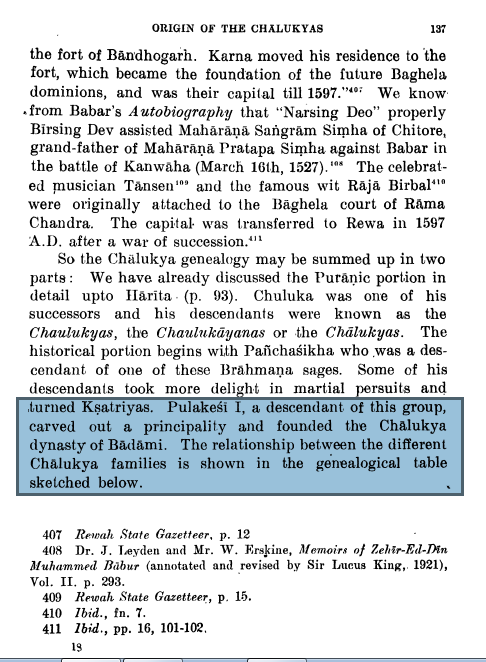

The Imperial Chalukyas have an origin that is much debated, as is the case with many dynasties in India. Orthodox Puranic History, however, is clear that they are 1 of the 4 Agnivamsas.

Origin

[6, 398]

[6, 398]

Tracing their origin to Udayan in the North, the Imperial Chalukyas would branch out and become one of the most consequential dynasties in Dakshinapatha’s history.

[13,6]

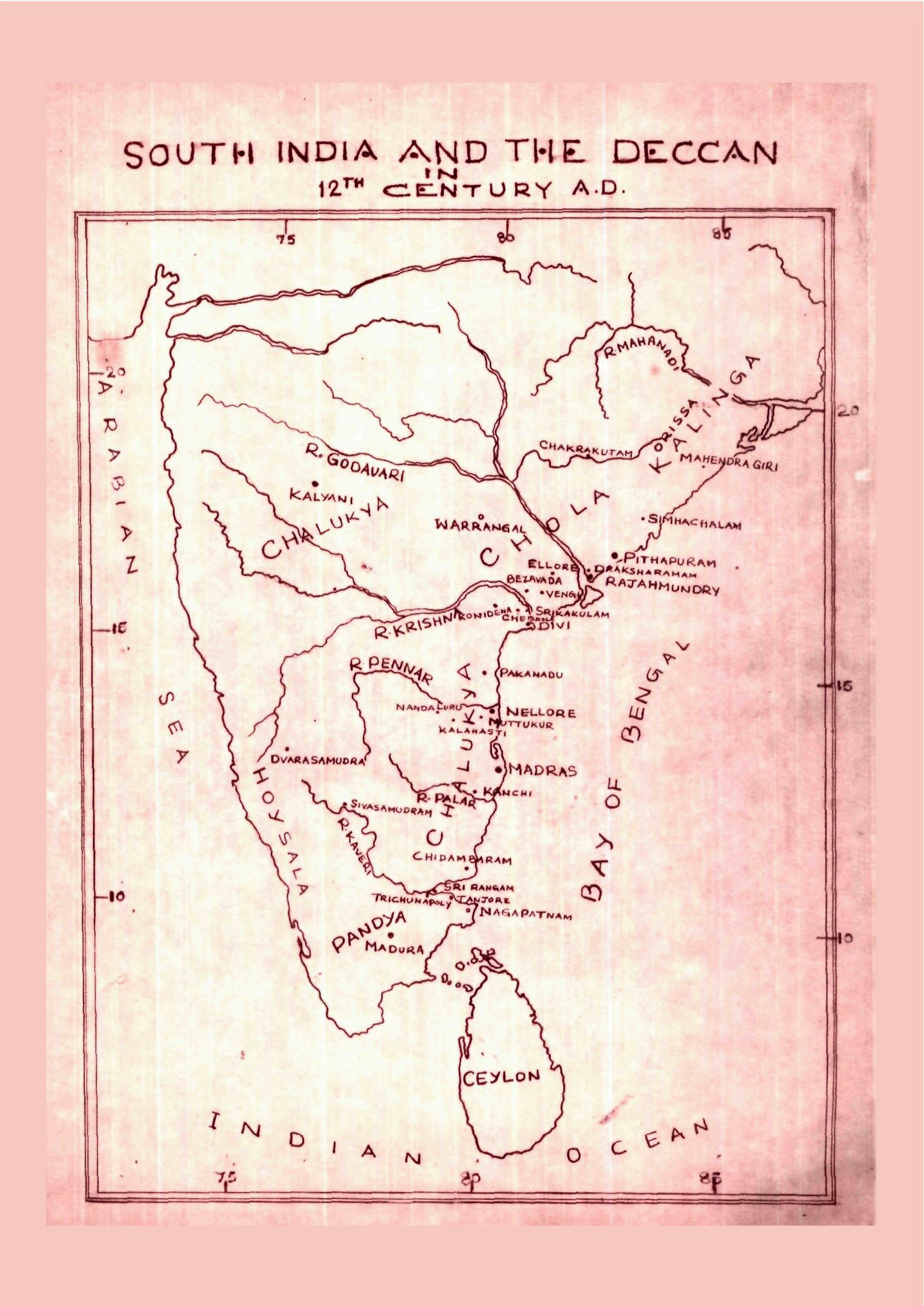

“The Eastern Chaalukya kingdom of Vengi was the bone of contention throughout; its rulers were allied to the Kalyaani Chaalukyas by descent but they were also beholden to the Chola who had restored them to their throne whence they had been driven into exile as the result of a civil war (at the end of the tenth century), and several dynastic alliances followed and brought the lines closer together until, in A.D. 1070, when succession failed in the Chola male line, the ruler of Vengi himself succeeded to the Chola throne. This was Kulottunga I. His great Chaalukya opponent was Vikramaaditya VI. Their rivalry filled the annals of South India for about half a century and made for the weakening of their respective empires under their less competent successors. The Hoyasalas of Dvaa(o)rasamudra, the Yaadavas of Devagiri, and the Kaakateeyas of Waarangal, all feudatory powers nurtured on the breast of the Chaalukyan empire of Kalyaani, came up in the latter half of the twelfth century and partitioned among themselves the territories of the parent empire.” [1, 6]

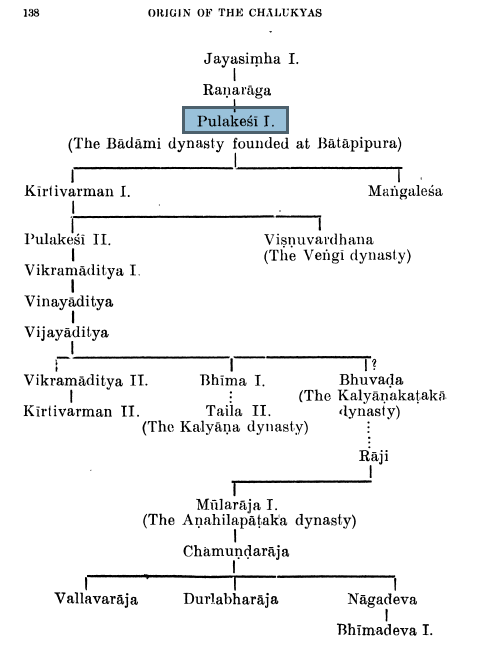

Vamsa Vrksha

It’s incipience, however, is traced back not to Aandhra, but to a neighbouring state.

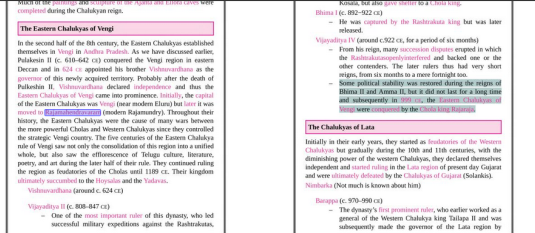

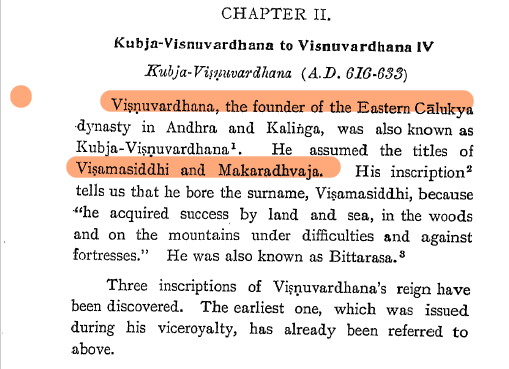

Eastern Chalukyas of Vengi

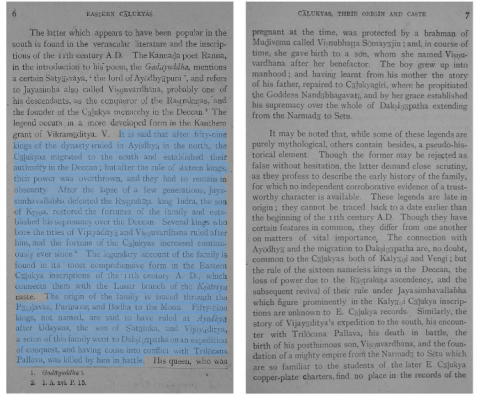

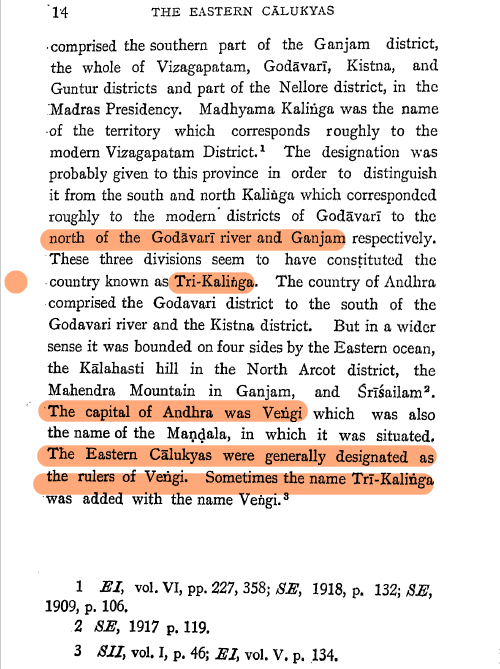

Vishnu Vardhana (624-642)

His general, Buddhavarman of the Durjaya clan, was a prolific conqueror. He slew the king Daddara, and he and his descendants would rule eastern Sattenepalle as a fief. [6, 18]

His general, Buddhavarman of the Durjaya clan, was a prolific conqueror. He slew the king Daddara, and he and his descendants would rule eastern Sattenepalle as a fief. [6, 18]

Jayasimha Vallabha I (641-673)

Jayasimha succeeded his father. His reign is notable for its separation from the Imperial Chalukya dynasty, following the disastrous defeat and death of Pulakesin II by the Pallavas.

Vishnu Vardhana II (673-682)

Mangi Yuvaraja (682-706)

Mangi Yuvaraja’s reign was not particularly notable. However, the period immediately following him would be notable for internal dissensions. There was a succession crisis, followed by a division of the kingdom.

Vishnu Vardhana III (719-755)

Vijayaditya I (755-772)

Vijayaditya would then succeed Vishnu Vardhana III. His reign would be significant not for the rule of Vijayaditya himself, but rather on account of the earth-shattering rise of the Rashtrakuta dynasty of Manyakheta. These Emperors would establish their paramountcy at a time when the borders of Indic Civilization were being challenged by the Abbasids.

Vijayaditya ruled for almost 2 decades, during which the Deccan plateau would witness these changes.

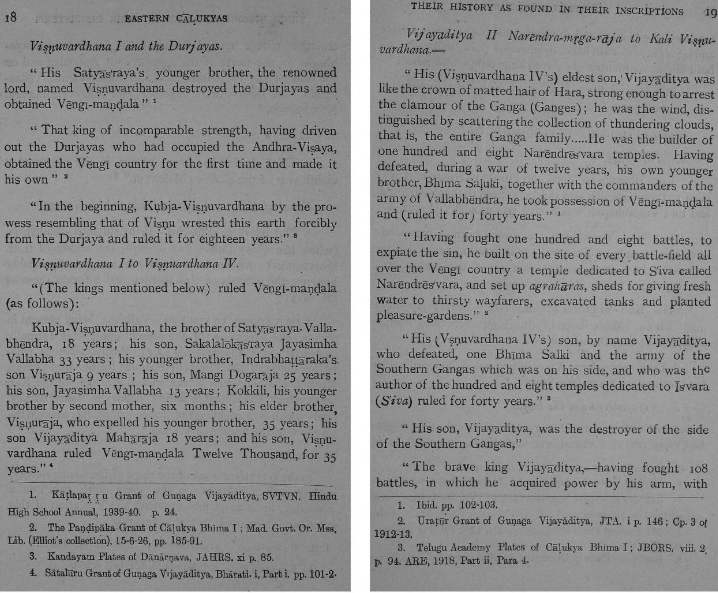

If Vijayaditya would witness the rise of the Rashtrakutas, then Vishnu Vardhana IV would bear the consequences. The Eastern Chalukya kingdom of Vengi would be vanquished by Govinda II, Yuvaraaja of the Rashtrakuta empire. He would acknowledge the supremacy of Krishna I, and rule as feudatory king. He would marry a Haihaya princess, and be succeeded by his son Vijayaditya II. [6, 45]

Vijayaditya II (808-847)

Vijayaditya then would attempt to expand elsewhere. He entered into a coalition with other powers such Sindh, Vidarbha, and Kalinga and contended with the second-most powerful potentate of India at the time, the Imperial Pratiharas. The coalition met with reversal and was comprehensively dispersed by Nagabhata II. [6, 52]

Having licked his wounds, Vijayaditya would then try his luck with the Naga chief of Bastar. He met with success here. All and all, his reign represented a military high point of the Eastern Chalukyas. He was an avid builder as well and is notable for his architectural contribution.

Vishnu Vardhana V ruled only for a few short months (~20). He was succeeded by Gunaga Vijayaditya in 844 CE. As a result, the next king of consequence was this potentate.

Vishnu Vardhana V ruled only for a few short months (~20). He was succeeded by Gunaga Vijayaditya in 844 CE. As a result, the next king of consequence was this potentate.

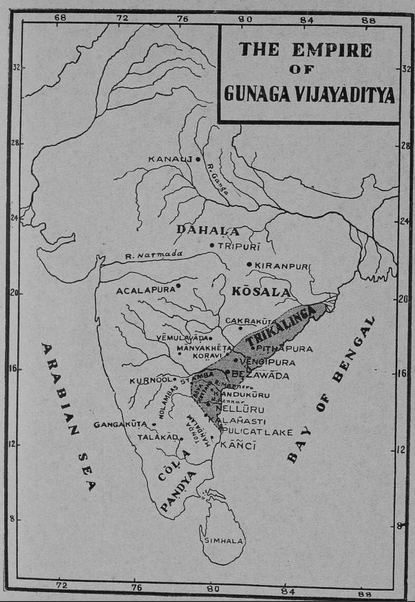

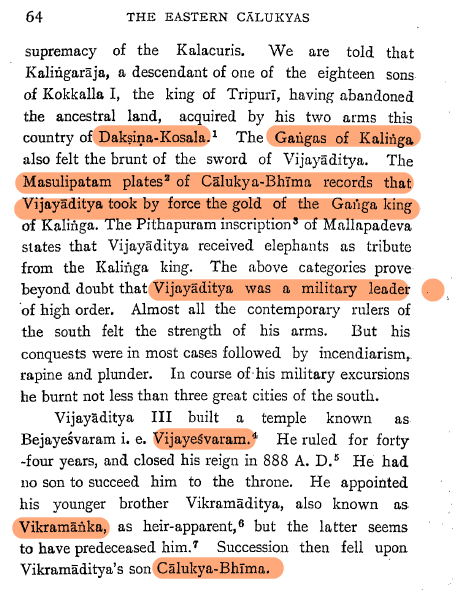

Gunaga Vijayaditya III (848-891)

[8, 129]

Gunaga Vijayaditya was among the most eminent kings of this dynasty. An avid conqueror, he embarked upon a digvijaya, and worsted the Pallavas, going on to wrest Nellore from them.

This would then commence the first contact between the Chola dynasty and the Chalukyas—one of the most consequential dynastic relations in the Dakshinapatha. The Chalukya dynasty would play a pivotal role in the rise and regeneration of one of India’s greatest imperial polities.

This would then commence the first contact between the Chola dynasty and the Chalukyas—one of the most consequential dynastic relations in the Dakshinapatha. The Chalukya dynasty would play a pivotal role in the rise and regeneration of one of India’s greatest imperial polities.

Gunaga would then cap off his reign with a signal victory over the Western Alliance of the Gangas, Nolambas, and Rashtrakutas. He would defeat them all, even the Rashtrakutas buttressed by their Kalachuri allies.

Gunaga would then cap off his reign with a signal victory over the Western Alliance of the Gangas, Nolambas, and Rashtrakutas. He would defeat them all, even the Rashtrakutas buttressed by their Kalachuri allies.

His force of arms did not go silent even after this achievement. He would then conquer Bastar State’s Dakshina-Koshala Kingdom, and sack its capital. From there, the Eastern Gangas would then feel his might, and the cupidity of his force, parting with much gold. Gunaga, more than any other Eastern Chalukya king, would be at the cusp of an empire. However, this digvijay concluded with little more than token submissions (the gorging of the Bastar state aside).

His force of arms did not go silent even after this achievement. He would then conquer Bastar State’s Dakshina-Koshala Kingdom, and sack its capital. From there, the Eastern Gangas would then feel his might, and the cupidity of his force, parting with much gold. Gunaga, more than any other Eastern Chalukya king, would be at the cusp of an empire. However, this digvijay concluded with little more than token submissions (the gorging of the Bastar state aside).

Chalukya Bheema (892-921)

Among the more eventful reigns in the dynasty, following that of his uncle, Chalukya Bheema’s first year was trouble. He would face an invasion by a Rashtrakuta emperor eager to restore his supremacy over Vengi.

However, King Bheema would respond with the trademark persistence of his dynasty, and drive out the invaders. He demonstrated his courage and power at the Battle of Niravadyapuri (Nidadavolu), and preserve his kingdom. He would go on to reign 30 years.

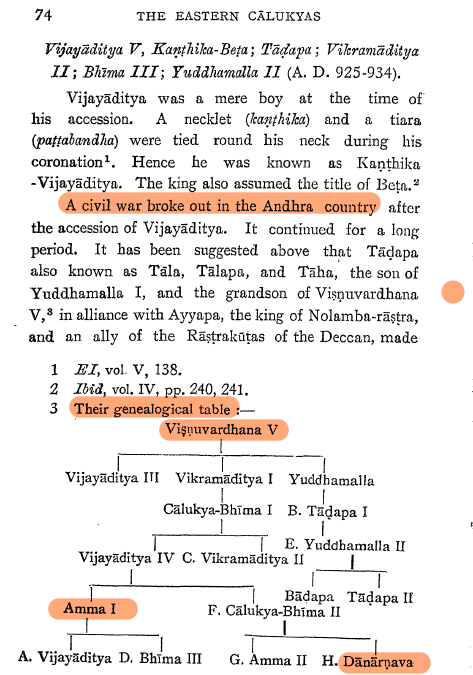

The curiously named Ammaraja I would reign only 7 years. This would be followed by a succession crisis that threatened the very existence of the kingdom. Indeed, the Chola dynasty would intervene to restore stability in the kingdom.

Vengi Chalukya Restoration

Ammaraja II (945-970)

Danarnava (970-973)

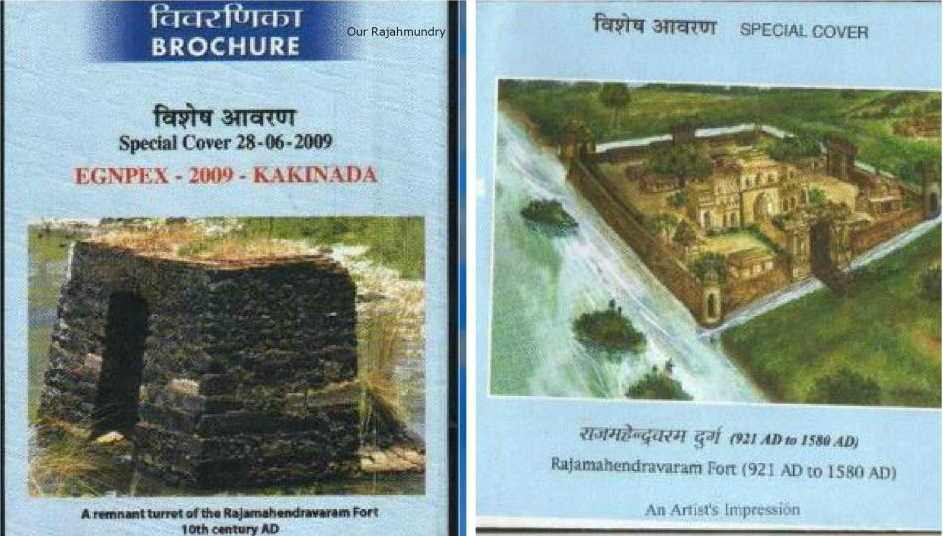

Danarnava (Dhaanaarnava) would restore the coherence of the Eastern Chalukya dynasty, and feature the rise of Rajamahendri as the capital of the kingdom and of Telugu culture. He would rise to the throne in 970 CE, and rule either 3 or 20 years, depending on the inscription. There would be an ebbing and flowing of claimants following his rule. Some assert Jatachola Bhima (973-1000) as presiding over much of this period. Regardless, he would ultimately be followed by Shaktivarman.

Shaktivarma I (1000-1011)

Vimaladitya I (1011-1018)

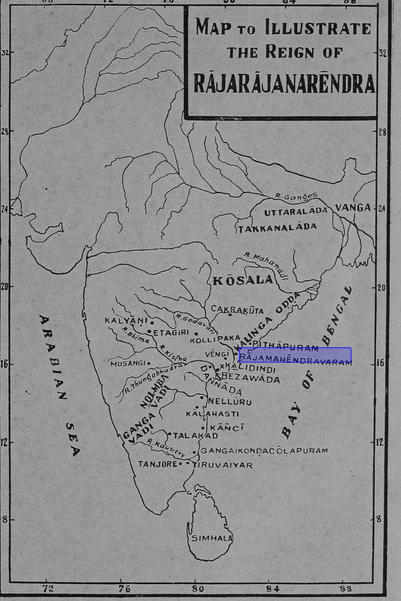

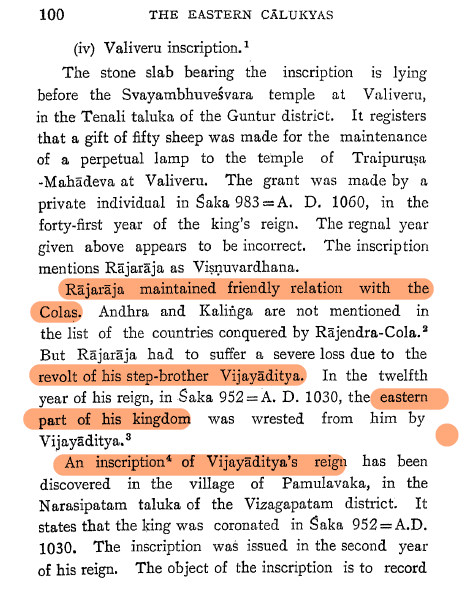

Raja Rajendra (1019-1061)

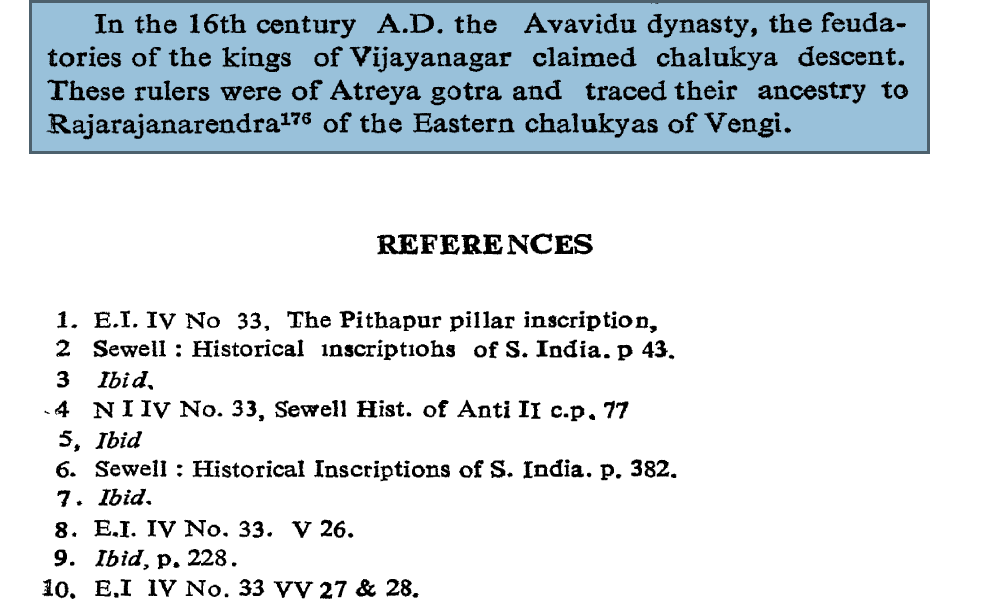

Undoubtedly the most famous king of this dynasty, Rajaraja Narendra is celebrated for his cultural contributions. Nevertheless, this period would be politically and militarily harmed by the revolt of his step-brother (himself a Chola on his mother’s side). The event would ultimately seed the decline of the Chalukyas, presaging the rise of the Kakatiyas.

Undoubtedly the most famous king of this dynasty, Rajaraja Narendra is celebrated for his cultural contributions. Nevertheless, this period would be politically and militarily harmed by the revolt of his step-brother (himself a Chola on his mother’s side). The event would ultimately seed the decline of the Chalukyas, presaging the rise of the Kakatiyas.

Vijayaditya III (1061-1075) [3, 310]

Due to the predeceasing of his heir, Yuvaraaja Shaktivarma, Vijayaditya III reclaimed the throne. However, the Vengi schism would not last long. Young Rajendra-Chola (Koluttunga) was chomping at the bit to reclaim the patrimony of his father, Rajaraja Narendra. From his maternal throne of Chola desa, he would relaunch his family’s bid for the throne, and place a viceroy there.

As a result, there is some discrepancy over when exactly the Eastern Chalukyas concluded. The Vengi lineage was displaced by the Chola-Chalukyas. Their reign, from Gangaikonda-Cholapuram would feature a tug-of-war with the Western Chalukyas over control of the Aandhra desa. This would finally conclude with the dominance of the Kakatiyas.

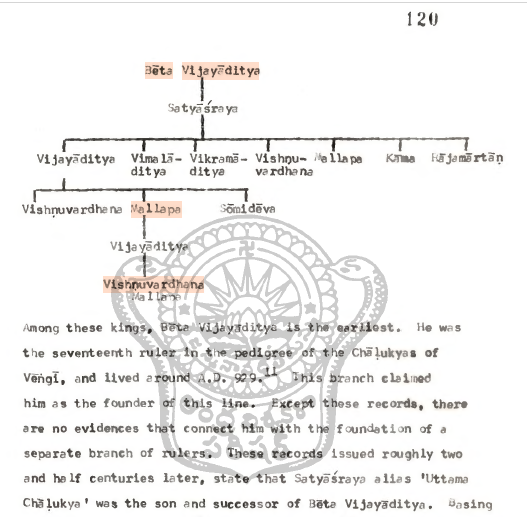

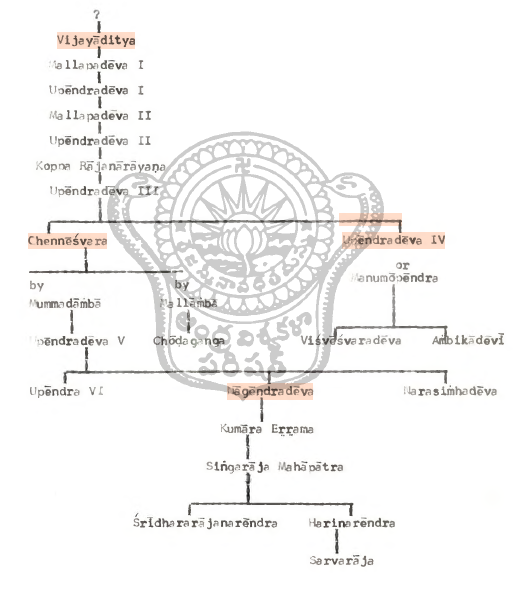

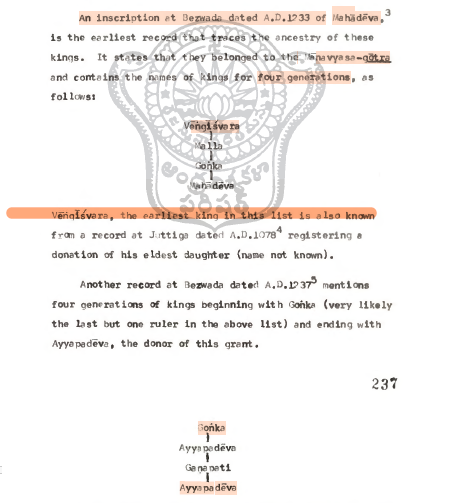

There were countless collateral and cadet branches of the Eastern Chalukyas (what to say of the Imperial Chalukyas?). There are a number of excellent works that attempt to catalogue them all. For brevity’s sake, we will merely attempt to cover some important ones.

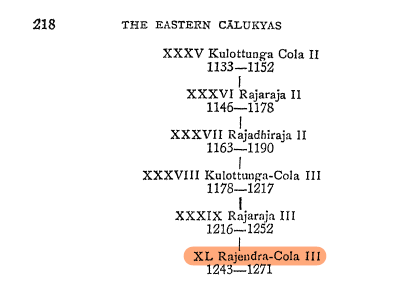

Chalukya-Cholas

Are the Chalukya-Cholas part of the Chalukya dynasty or the Chola dynasty? This question is one that has arisen off and on. Patrilineally they are certainly Chalukyas, but having ensconced themselves in Chola desa and having faced off first against Vijayaditya’s descendants followed by the Western Chalukyas, they were effectively operating as Cholas. Therefore, they deserve to be discussed as such along with the Telugu Chodas, to whom they are related. This can be done elsewhere. Nevertheless, here is the conclusion of that famous family tree featuring the remaining nominal members of the Eastern Chalukya mainline.

There are other lineages that subsequently arose either as cadet branches or outright offshoots.

There are other lineages that subsequently arose either as cadet branches or outright offshoots.

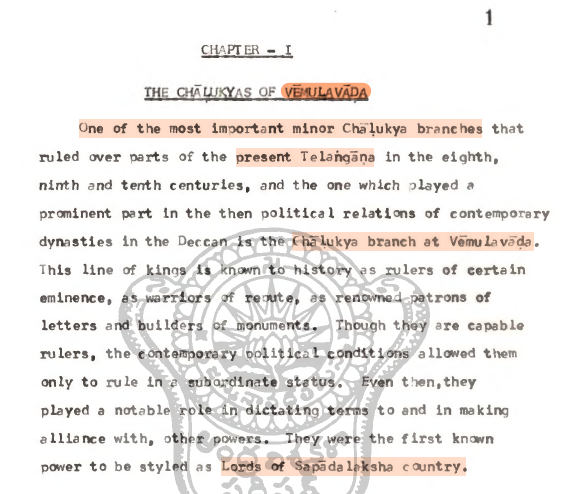

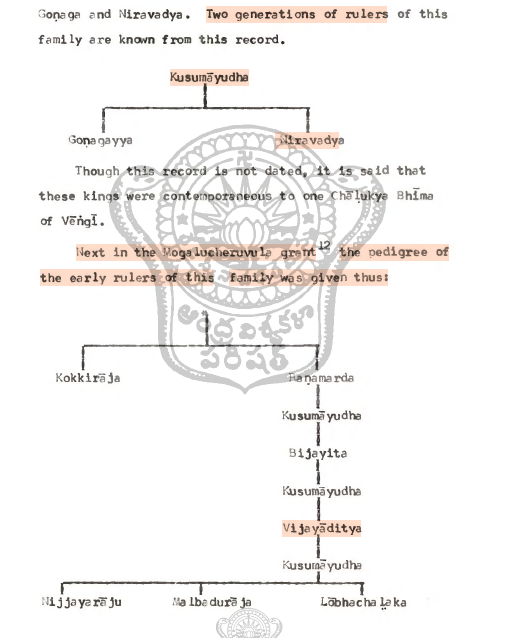

Among the notable lineages is this Chalukya branch. Vemulavaada is famously in Telangana state. The existence of this branch is proof-positive of the connection between Telingana region and the old Aandhra desa.

Chalukyas of Elamanchi

Chalukyas of Nidadavolu

More poetically known as Niravadyapuri, the city of Nidadavolu was the site of a famous Eastern Chalukya battle. It is no surprise, therefore, that a particular lineage ensconced itself here.

Legacy

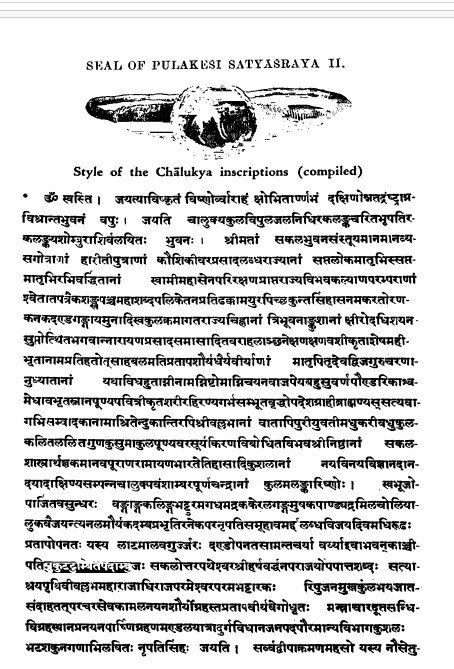

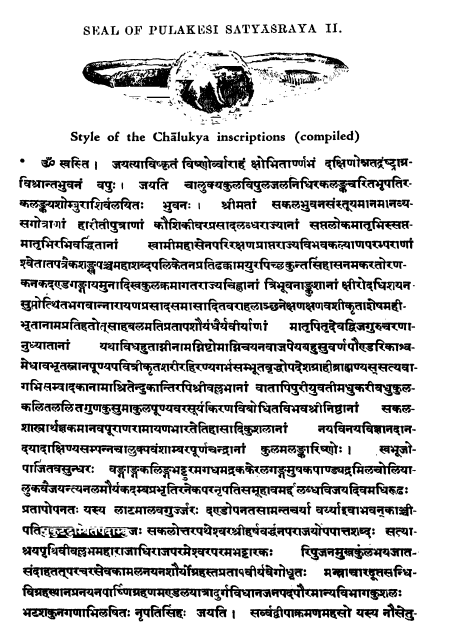

The legacy of the Eastern Chalukyas cannot be minimised. Owing their rise to Pulakesin II Satyaasraya, they would assert their independence and even rivalry with the Western line, in the coming centuries. Nevertheless, the administration the Eastern branch established would come to define the character and quirks of Telugu political communities.

The legacy of the Eastern Chalukyas cannot be minimised. Owing their rise to Pulakesin II Satyaasraya, they would assert their independence and even rivalry with the Western line, in the coming centuries. Nevertheless, the administration the Eastern branch established would come to define the character and quirks of Telugu political communities.

Administration

The Seal of Rajaraja Narendra established the character of his rule. He and his predecessors would gravitate from the more centralised rule of the Satavahanas and Pallavas to pursue a more feudal set up. They featured feudatories more than vassals and ruled a number of nadus and desas as part of this set up.

The Seal of Rajaraja Narendra established the character of his rule. He and his predecessors would gravitate from the more centralised rule of the Satavahanas and Pallavas to pursue a more feudal set up. They featured feudatories more than vassals and ruled a number of nadus and desas as part of this set up.

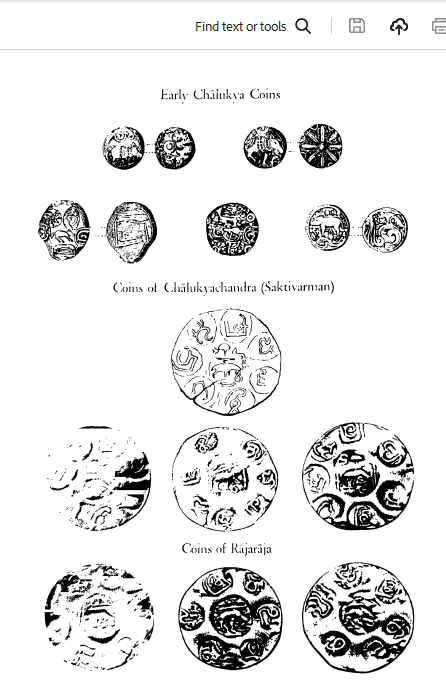

The Chalukyas were no slouches in the realm of Coinage either. Copious coin hoards are found throughout the Deccan plateau bearing the mudra (mark) of this royal dynasty.

A number of famous cities and towns in today’s Aandhra can be traced back to this period. Among them is the famous Kurnool. Kandhanavolu=Karnool

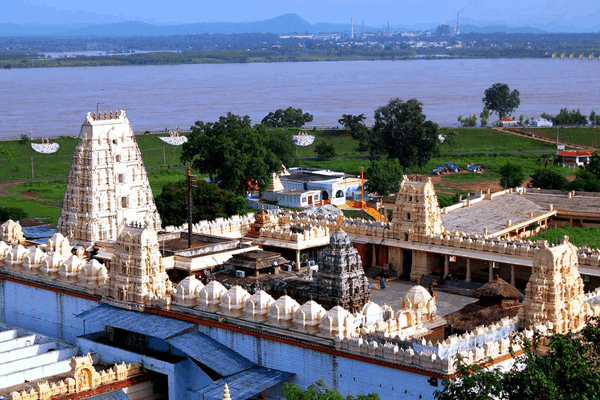

Perhaps nothing stands as much a testament to the impact of the Eastern Chaalukyas as the City of Rajamahendri

“After the sack of Vengipura and also Vijayawada Ammaraja I felt the need to build a new capital strategically located for conducting campaigns against his enemies, both within the kingdom and outside. So on the northern bank of the river Godavari he founded a new city and named it Raja Mahend[ri] after his title Raja Mahendra. Within a short time Raja Mahendri or Rajahmundry, as it is popularly called, developed as the cultural capital of the Andhras, a position it still retains.” [10, 45]

There were also notable changes introduced by the administration of the Eastern Chalukyas.

Despite their tremendous cultural achievements, the Eastern Chalukyas (and Chalukya Dynasty in general) themselves instituted arrangements that transgressed varnashrama dharma. Braahmanas (whose task is primarily teaching of veda-saastra, & agriculture-trade only for survival) were being appointed at large scale as ministers (normally mere councillors are acceptable, but not cabinet ministers) and even some as generals….

“In consequence of the growing importance of the temple, the brahminical community which educated well in the science of state administration began to search for alternations which they had before them to select either to migrate to places where they could find royal support to their scholarship or to give up their traditional professions and to enter the state service at the royal court. As a result, a good number of Brahmins were either migrated to new places and some of them joined in the state service under the Eastern Calukyan state and did a great deal of service to the state. During the regime of Gunaga Vijayaditya (848-891) many brahmin generals served in the army.” [3, 184]

As a result, many members of the fourth varna also began to rise as not only agriculturalists and merchants, but also became lesser aristocracy (i.e. landed gentry)—previously only for Kshathriyas. “however, the rest of the state military as well as civil officers were consisted of personnel belonged to other sections of the community. They are placed in…posts like Mudiseli, Mulabhritya Padihari, Padalu, Pregada, Dandanayaka, Sarvadikari Mahamandaleshwara. Even in temples they held such responsible and respectable positions as that of Bhandaruvaru. The Srikarana a high rank officer in the temple of Srikurmam was Kayastha. At the village level the Reddis, karnams, nayakas, etc. held by the peasant elite groups.” [3, 185]

[8,56]

“in contrast to the Calukyan state where we could see the brahminisation of the state in terms of the administration and religion, in the case of the Kakatiyan state this process went on in a different way i.e., the brahminisation and sanskritisation of religion and the non-brahminisation of state. “ [3, 185]

It is worth asking whether changes in religion were also at work here, from the rise of the Kapalika and Kalamukha sects.

Cultural Contribution of the Eastern Chalukyas

The cultural impact of the Eastern Chalukyas cannot be minimised. It is a dynasty that was accomplished in every way, and to this day, left a notable mark on all of Telugudom

“The Chalukya kings ruled the Andhra country between 6th and 11th centuries. During this period, the arts of Music and Dance were patronized by temple institutions and royal courts. For instance, Gunaga Vijayaditya (9th century), a Chalukya king, had the title ‘Gaandharvavidyaa praviina” (Ex-pert in Music). Likewise another king, Chal[u]kya Bheema (10th century ), honoured a woman, Chellava by name, for her ex-pertise in music, by donating a Maanya (agricultural land) at a village called Attili. It is reported that Chellavva’s father, Mallappa, was a great musician like sage Tumbura. Chamekamba, the wife of 2nd Ammaraju (10th century) was repurted as an expert in the art of Dance. Badapudu, who defeated 2nd Ammaraju in battle and [o]ccupied the Vengi king-dom, patronized drama artistes and musicians. In the sculpture and statues of this period musical instruments like Viina, Flute, Mridanga and Cymbals are found. A sculptural piece found at Chebrolu, depicts a concert of dance and orchestra.”[2,21]

“Ko:laatam, which is a mixture of dance and song appears to be the chief popular amusement of this period.”[2, 21-22]

However, folk music and dance was not the only contribution. High culture was also given generous patronage.

“The first literary work written during the rule of Chalukyas (11th century) was Aandhra Mahaabhaaratam (a Telugu trans-lation of Sanskrit Mahaabhaaratam). In this work, Poet Nannaya describes Nritta, Giita and Vaadya (dance, song and musical instruments) in connection with Raivataka celebrations. He re-fers to a number of dance musical instruments such as Mridanga, Mukunda, Ve:nu, Kaahala and Pataha. Further, mentioning that ‘people danced sounding their cymbals as per Taala. Nannaya gives information of Taala which is a vital component of Dance. As Nannaya was describing a celebration he did not mention Viina. All the instruments he cited are those played while stand-ing or walking”. [2, 22]

[7, 127]

Conclusion

The Eastern Chalukya dynasty was one of the most consequential in Aandhra desa, and indeed, in all of India. Its pivotal influence (indeed grafting onto the Imperial Chola line) would influence the course of that polity and Southern Indian history in general. The de-construction of the Chola machine meant that the Turkified North had only to face a divided South in its campaign for conquest and converts. The Eastern Chalukyas were patrons of culture and the Telugu language itself, which would later come under attack by these very Turks of the North. Tragically, many on the other side of the Polavaram seem to have forgotten this.

Of late it has become fashionable to retroactively attribute identities to words. The goal of this, of course, is to marginalise the traditional word for a preferred one—usually to advance a political agenda. Having split a state, the goal then is to take this coloniser-popularised term to divide a region from not only it’s sub-regional connections, but its connection to Indic/Sanskriti civilization itself. The word trilinga has long been connected to the word telinga. For anyone with basic knowledge of tadbhavas, Telinga is a mere prakritism of the Sanskrit trilinga—which every school child knows as the 3 lingas in Coastal Aandhra (Kosta), Telangana, and Rayalaseema. But in the quest to qutb-ise not only telangana but coastal Aandhra itself, efforts have been made to disconnect a word from its etymology and a people from each other.

Eastern Chaalukya inscriptions show Aandhra repeatedly as the identity of the entire Telugu region. Thus, the drive to impose “telingana” (derivate for telinga/trilinga) as THE identity not only for nizaami doras, but for all Telugus, only demonstrates how insidious the original plot was to destroy the Aandhra identity. Great poets like Pothana Mahakavi clearly referred to the Telugu Bhagavatamu as Aandhra Bhaagavatamu. Even the Telugu Mahabhaaratam of Nannayya is called Aandhra Mahabharatamu. And the Saatavahanas who ruled from Amaraavathi, and originated in Srikakulam, were called Aandhras in the Puraanas. But according to rachakonda dora fans, only british and nizaami colonial indologists are correct…

The civilized culture and people of a region are themselves the authorities on their own history and tradition. Those who rely on foreign interpretation and assistance, are themselves foreign derivatives—who should be dismissed as such.

In contrast, the Eastern Chalukyas who came as neighbours would embrace the local culture as their own, and became synonymous with the Aandhra Mahabhaarathamu and the Aandhras themselves.

References:

- Sastri, K.A.Nilakantha. A History of South India. New Delhi: Oxford. 2015

- Bai, Kusuma K. Music-Dance Forms And Musical Instruments during the Period of the Nayakas.

- Rao, T.Dayakar. Trade and State Craft in Medieval Andhra: A Reappraisal (600-1600 AD). Delhi: B.R.Publishing. 2016

- Kota, Venkatachalam Paakayaaji (Pandith). Chronology of Ancient Hindu History Part I. Vijayawada: AVG. p.121-133

- Satyasray, Ranjit Singh. Studies in Rajput History. Vol.I: Origin of the Chalukyas. Sanskrit College: Calcutta. 1937

- Ganguly, Dhirendra Chandra. The Eastern Chalukyas. Benares: Tara Printing. 1937

- Murty, K.V. Krishna. Ancient Indian Mathematicians. Hyderabad: Institute of Sci.Research on Vedas. 2010

- Kamath, Suryanath U. A Concise History of Karnataka. Bangalore University. 1973

- Malampalli, Somasekhara Sarma. History of the Reddi Kingdoms.Delhi:Facsimile Publ. 2015

- Rao, P.R. History and Culture of Andhra Pradesh. New Delhi: Sterling. 1994

- Kolluru, Suryanarayana. History of the Minor Chalukya Families in Medieval Andhradesa. Visakhapatna: Andhra University. 1984

- The History of Andhra Country, 1000 A.D.-1500 A.D.: by Yashoda Devi The History of Andhra Country, 1000 A.D.-1500 A.D.: Administration, …