Following our Article on traditional Andhra Economic History, a study of the modern Economic Society becomes the natural next step. Unlike Ancient and even Early Medieval History, this Colonial and Post-Colonial History is not only lived experience, but relevant to modern Aandhras who have yet to fully decolonise. After all, they still refer to “phillim-collections” as “How much in naizam? How much in ceded?”. These Telugu regions (Telangana & Raayalavaari-seema have their own identities beyond colonial history and foreign reckoning).

To fully decolonise, it must not only be politically and intellectually, but also culturally and economically. The idiots who celebrated “BritanniaFilmfare Awards” in India should understand why it is they are still buying Britannia biscuits, despite having nothing to do (allegedly…) with Britain.

Therefore, Andhra Economic Society must become a study of its own.

Introduction

In our previous article, we studied how indigenous economic organizations (sreni (guilds), puga (business concerns), sarthas (caravans), and nigamas (corporations)) all existed. Some, like the 500 Svaamis of Ayyavolu were shared with neigbouring regions like Karu desa (Aihole), and Chola desa (Kanchi). The communities that drove these organisations Komatis (Vaisyas) and Balijas (Veera Balanjyas) exist today—albeit sometimes under different designations. Some became Naidus and others remained as Settis. Some were even ruby and precious stone traders in far off places like Burma (Myanmar). Their descendants, however, retained prominence not only as politicians and merchants, but as modern industrialists owning industrial giants. Many other communities also rose to join them and even surpass them to dominate Aandhra’s economy today and give a Southern riposte to the fabulously wealthy Marwaris and Agarwals.

Pre-Colonial Historical Recap

To cover the full exploitative charithra of the period from 1323-1948 (or more continuously, 1565-1948 CE) will require a sequel article to our previous one on Andhra Economic History. What is apparently a matter of pride to some circles in modern Telangana was in fact a terrible period in all of United Andhra Pradesh. Whether they are from Turkestan or Englistan, an invader is an invader and is there to exploit. Every once in a while there might have been a less criminal ruler, but the real locals of the land, the true bhoomiputras are the Telugus of Telangana, Rayalaseema, & Coastal Andhra. Those who wish to live alongside them, must learn that respect is a 2 way street.

The Andhra Satyagraha, the Telangana Rebellion, and Operation Polo firmly established both de facto and de jure that Telangana & Andhra Pradesh are Telugu states (formerly UAP with Hyderabad as capital) within the Republic of India.

However, a brief recap of Pre-Modern UAP is necessary to gain a picture of Modern UAP. We have data here through 2009 (with Bifurcation officially occurring in 2014—now a decade ago).

Hyderabad nizami Oppression of Telangana

“The people of Hyderabad suffered from double disadvantage. Apart from the overall domination of the British, they had to bear the oppressive rule of the Nizam, who being of [Turkic] origin, had no sympathy for the nationalist and cultural aspirations of his Hindu subjects who formed 88 percent of the population. In spite of the suffocating atmosphere of the State, the people of Hyderabad city, especially the small group of English-educated elite could not remain immune from the social and political developments of British India. The ‘Chanda Railway Agitation’ of 1883 is the beginning of the growth of public opinion of Hyderabad State.” [2, 135]

Contrary to modern slogans of harmony and brotherhood, the nizam Hyderabad state was anything but, to the Telugu Hindus of Telangana. “Taxation under Nizam’s rule was oppressive. Sri Raavi Narayana Reddy’s Veera Telangana provides a succinct portrayal of how Nizam used to fleece the poorest of the poor. Taxation in the Hyderabad state was 25% to 300% more than in other areas of the country. Peasants were required to pay a fixed tax called a levy, which they had to pay regardless of the output derived from the land. If there was a dispute between two people, before it could be settled, they had to pay a ‘dispute tax.’ People were taxed to death—literally. If a family member died, you could not cremate that person unless you paid the ‘ash tax’. Then, there was a war tax to finance the British in World War II.” [5, 139]

‘Telangana’ means ‘Land of the Telugus’, and yet here, Telugus could not be educated in, gain civic jobs for, or speak their own language without mockery as ‘Telangi-Bedangi’. If urdu were similarly mocked today for its guttural, phlegm-based sounds as ‘urdu-shurdu‘ how would hyderabadi razakars feel? And yet, the suppression was not only political, cultural, and religious, but also economic.

“The Government did not allow even the private institutions to impart education in the language of the people. The people of the State did not even have the elementary rights of citizenship. The condition of the agricultural tenants was deplorable. The big landlords known as Maktedars and Pattedars subjected their tenants to serfdom and slavery known as baghela and vetti chakiri (Begari).” [2, 267]

“There is no denying that Telangana is behind the other regions when it comes to the literacy rate. However, it is important to note that the legacy of a low literacy rate in the Telangana region goes back to the Nizam’s rule, when only 5 in 100 people could read or write.” [5,365]

Telangana was not alone in this suffering. Marathwada now in Maharashtra and Northern Karnataka (now curiously featuring an RSS-driven Uttara Karnataka movement?!), also groaned under nizami maladministration (why should there be linguistic state division due to foreign colonial maladministration?). This was not only political but economic. For this reason, regions under Hyderabad princely state were far more under-developed, exploitatively taxed, and educationally disadvantaged.

“An alarming spectacle of poor economy prevailed in this region which is a sharp contrast to the economic prosperity and huge wealth that existed at Devagiri during the period of the Yadavas. The economic situation was equally good during the Rashtrakutas when the famous Kailasa was wrought and also at the time of the Satavahanas when Pratishtanapura (Paithan) was not only their capital but also an important commercial centre. It has been shown that mal-distribution of resources and heavy concentration of wealth in the hands of the feudal over-lords and the ruling family were the chief maladies with which the people suffered. The Nizam was indifferent towards the developmental activities such as communications, industrialisation and irrigational improvements. It is the legacy of the Nizam’s autocratic rule for over a period of about 225 years.” [4, 195]

Study of this period demands a more in-depth post. However, this article features merely a recap, with future works necessitating complete comprehensive study.

Colonial british Period

The situation of Seemandhra (Kosta (Coastal Andhra) and Rayalaseema), was not that much better. The terrible starvation that occurred in the Nineteenth Century alone blighted british rule in India (particular the South & East) beyond belief for today’s toadies. “Andhra suffered from severe famines in the nineteenth century. The most severe famine commonly known as the Ganjam famine occurred during the years 1865-1866. ” [2, 66]

“Famines occured in other districts also due to the lack of irrigational facilities. The Rayalaseema area became a famine-stricken area. Not less than 11 famines occurred during the latter half of the last century [1800s]. Thousands of people died on roadsides in the districts of Cuddapah and Kurnool. Visakhapatnam district was also affected by famine” [2, 67]

Things got so bad due to british mismanagement (or malevolence…) that there were grain riots in Madras Presidency. “Another effect of the famines were that a large number of people especially in Guntur and Cuddapah districts were converted into Christianity by foreign missionaries who opened famine relief camps.” [2, 67] As such, british rule created a problem (famine) then provided a solution (famine relief camps—for a religious price of course…).

The overly famous and now-outdated Godavari Anicut of 1852 did address some of the issues, but it did so too late. Though a modern replacement was named for its Chief Engineer (Arthur Cotton of the eponymous barrage), Guntur suffered terribly in the preceding decades. “During the year 1833-34 the famine, popularly known as the Guntur famine, brought untold misery to the people. About 40 percent of the total population of Guntur died during these two years. Besides Guntur, Machilipatnam and Rajahmundry were also affected by the drought. The terrible destruction of the population and loss of revenue forced the Company to construct major irrigation works on the rivers like Godavari and Krishna.” [2, 55]

The Dowleswaram Barrage and Krishna Anicut later improved the situation, but for a select few and not the masses at large. An administration focused on exploitation of resources (even human resources…) rather than the well-being (yogakshema) of the populace, will never properly irrigate to sustain the people. If the same people who created the problem (famine & commodity farming at gunpoint) then provide a solution (3 measly anicuts + conversion factory famine relief) then do their statutes deserve annual abhisekham even to this day? Leaders of the self-appointed “self-respect movement” should introspect accordingly.

Rayalaseema (then called Ceded Districts, as they were ceded by hyderabad state to the british east india company), would not have a proper water supply again until the Telugu Ganga project of the modern era.

Decline in Handicrafts

Things did not stop with loss of food. With loss of food and land came also, loss of livelihood. “With the advent of the Crown’s rule the condition of the artisans became miserable. The different handicrafts were unable to face competition from machine-made goods and a large number of artisans were thrown out of employment. No new industries were established to absorb them. Many artisans left the country to seek employment as Coolies in Burma, Malaysia, & other countries.” [2, 67]

As will be established in the aforementioned Sequel article, the destruction of handicrafts was not a mere by-product of the Industrial Revolution, which commenced in 1800. There is evidence in the late 1700s itself that the East India Company was ruining independent artisan industries at scale. It was calculated and purposeful policy to reduce India from a world manufacturer to a mere market or supplier of raw materials, at best. This in turn exacerbated the crop selection of farmers, who switched from traditional subsistence + surplus profit, to plantation commodity farming—resulting again, in famine. Like a casino where the house always wins, here the Company always profits. As a result of this, there were Revolts at Rekapalle and Rampa, even preceding the great Alluri Seetarama Raju.

Either way, this provides the requisite depressing picture of pre-Independence India, and how United Aandhra in fact groaned under its double colonial rule (some would say triple…). Having provided the prior picture, one can now understand subsequent policy and why the focus to address immediate malnutrition and land reform was so pivotal.

Post-Colonial United Andhra

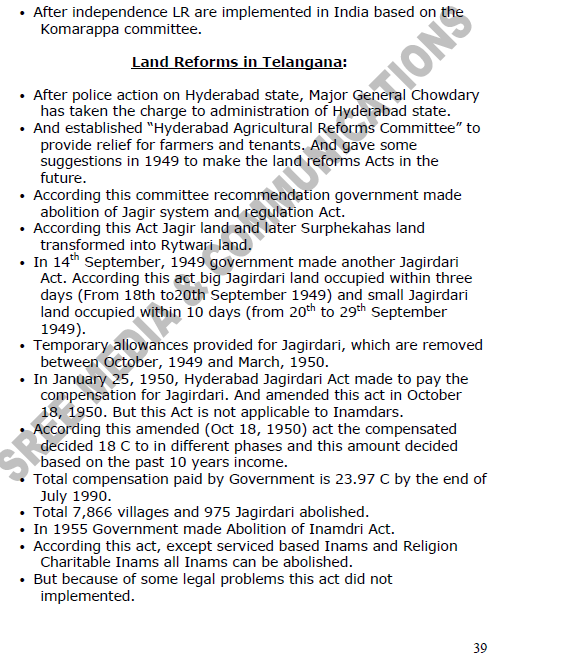

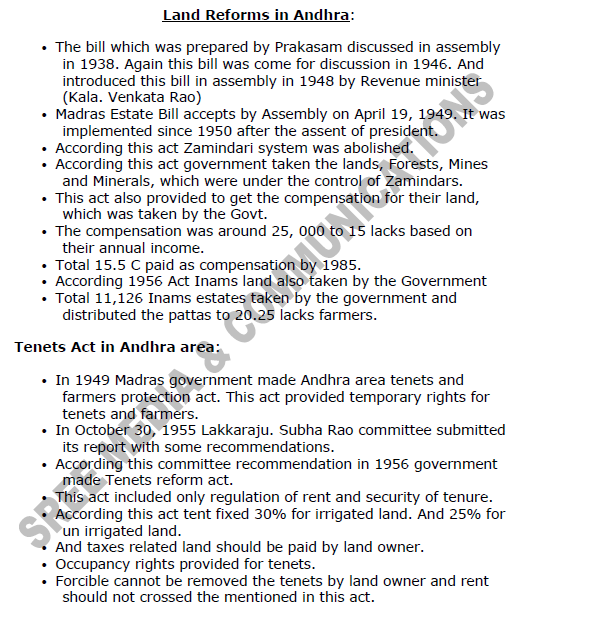

India achieved Independence in 1947, Telangana was Liberated in 1948, and the States Reorganisation Act was passed in 1956. The creation of United Andhra Pradesh (Vishalandhra) necessitated changes in not only the political system, but also in the economic system. The Feudal System in nizam Hyderabad & Colonial System in Seemandhra necessitated modern reform.

Prosperity is ensured not simply by demonising the wealthy, but by growing the pie. Some redistribution of land from feudal zamindars was necessary to prevent a naxal/communist revolution. Indeed, land ownership today should again be examined on an all-India basis (much of it owned by Non-Indians…). However, up-from-the-bootstraps entrepreneurs should be celebrated as they are today. It is honest entrepreneurship that grows the pie.

Prosperity is ensured not simply by demonising the wealthy, but by growing the pie. Some redistribution of land from feudal zamindars was necessary to prevent a naxal/communist revolution. Indeed, land ownership today should again be examined on an all-India basis (much of it owned by Non-Indians…). However, up-from-the-bootstraps entrepreneurs should be celebrated as they are today. It is honest entrepreneurship that grows the pie.

Public Finance

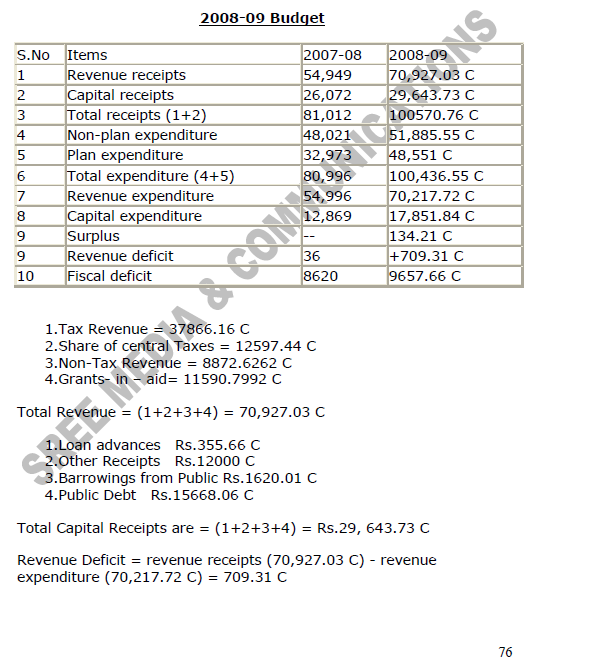

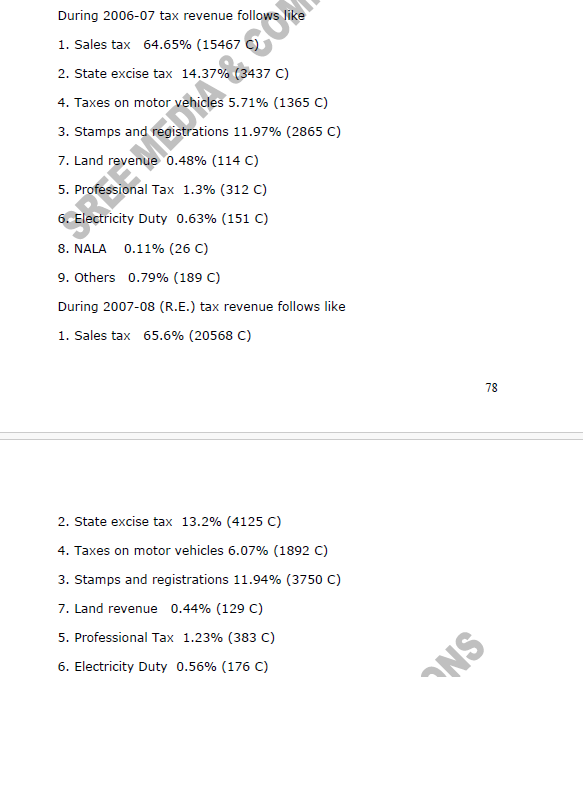

United Andhra Pradesh into 2009 was actually a Revenue & Capital Surplus state. It was among the best managed (especially through 2004) and oppressive nizami Hyderabad had become prosperous Cyberabad by the investments of Telugus. The breakdown of tax revenue is given below (percentage of revenue, not rate of taxation, thankfully!).

United Andhra Pradesh into 2009 was actually a Revenue & Capital Surplus state. It was among the best managed (especially through 2004) and oppressive nizami Hyderabad had become prosperous Cyberabad by the investments of Telugus. The breakdown of tax revenue is given below (percentage of revenue, not rate of taxation, thankfully!).

t Public Debt

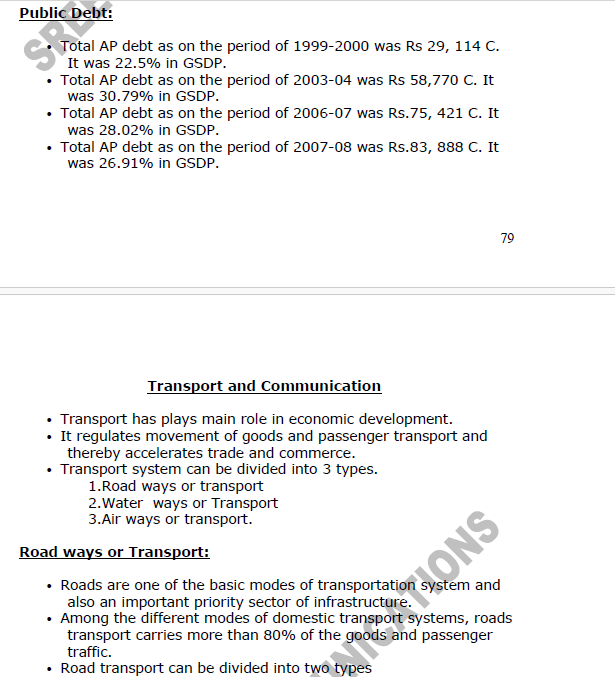

Public Debt

State Gross Domestic Product (SGDP)

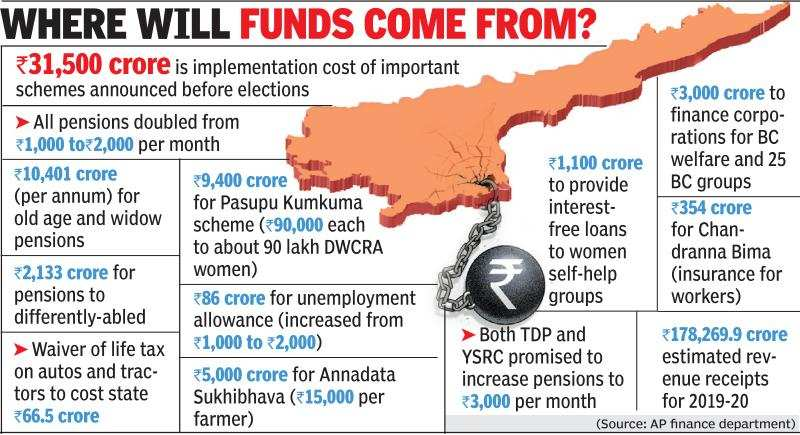

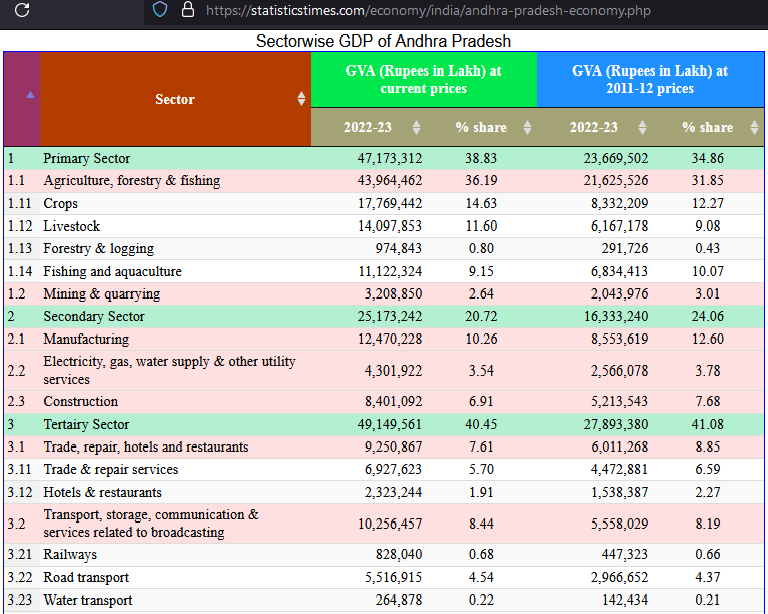

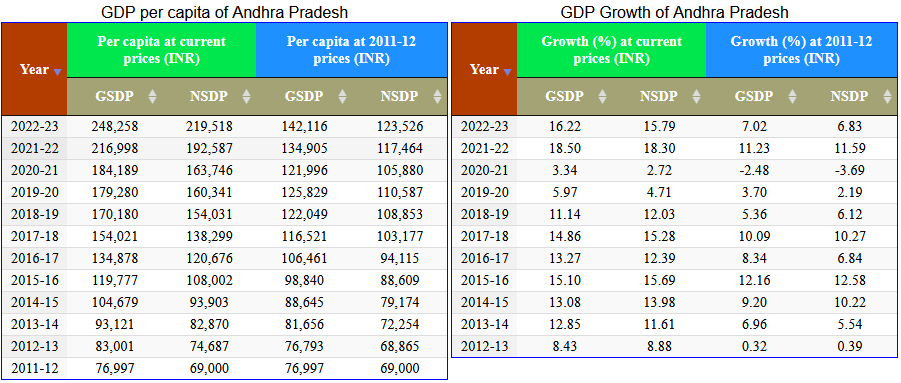

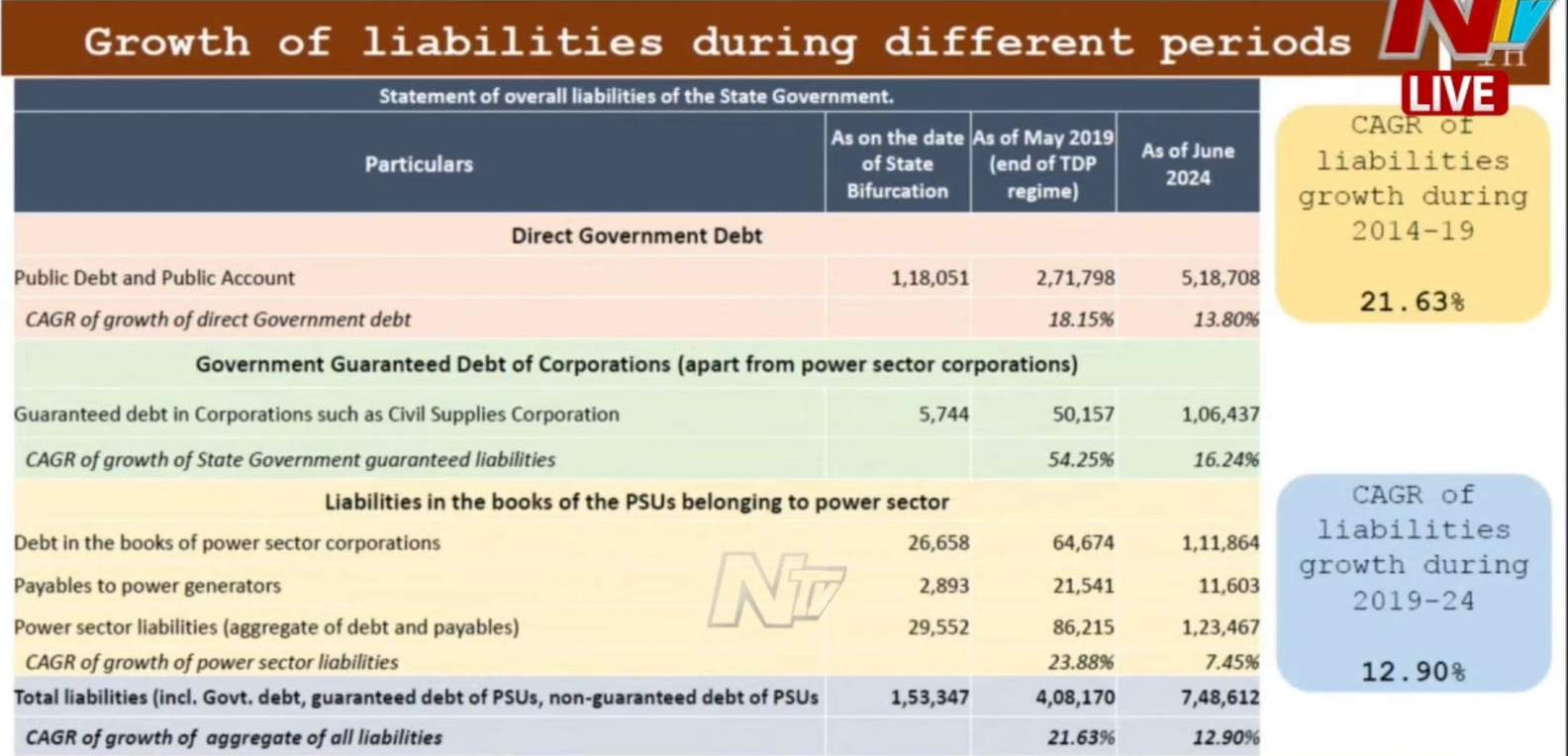

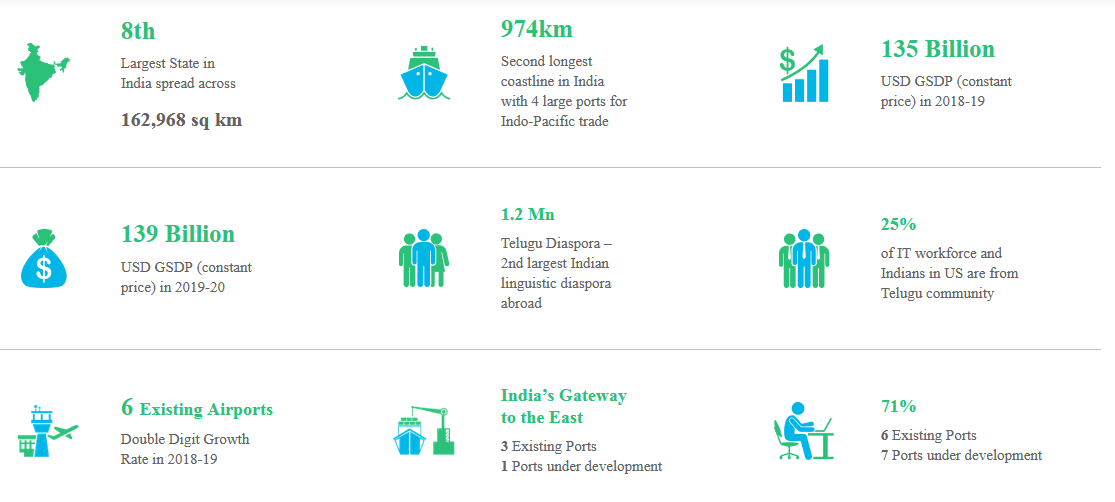

Gross Domestic Product, as most know, is measured by Consumption + Investment + Goods & Services Produced + Export-Import. SGDP is the State Gross Domestic Product. New Andhra Pradesh State’s most recent SGDP is $139 Billion. The estimated total liabilities is 9.74 Trillion Rupees (or $121 Billion).

Fiscally, Andhra Pradesh today is in a tight spot.

“The debt to GSDP ratio of AP has reached 33.5% if the debt raised from RBI is considered.

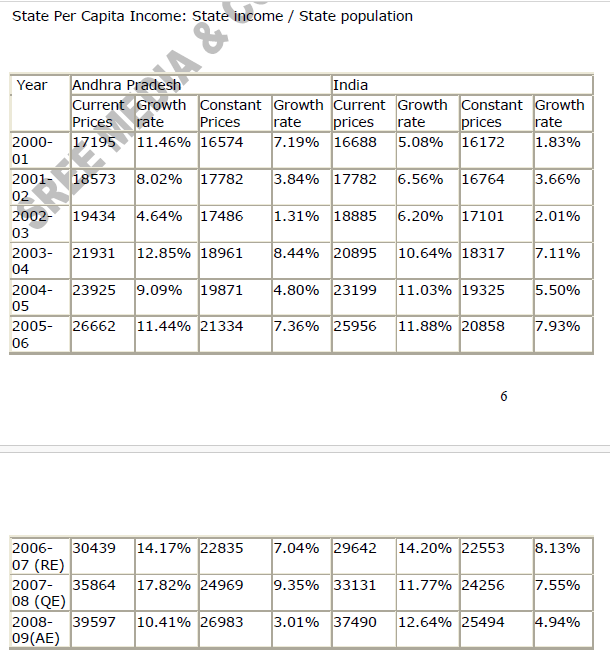

State Per Capita Income

A State is more than just its SGDP, it is also defined by its Per Capita Income (PCI). In this regard, UAP was among the better ones in the Republic of India. However, its problem lay not in mean income (skewed by the assorted crorepathis), but in the median income (particularly in formerly nizam administered Telangana). Given the high rates of Growth in Andhra Pradesh, its per capita income remains promising today. Here is a look below in dollars. In 2022, Andhra Pradesh PCI was estimated to be $2602 (₹192,548).

Categories

However, an economy is more than just the state of Public Finance; after all, that is the difference between exploitative foreign colonial rule and independent democratic governance. A proper economy possesses both Public and Private Sectors as well as Organised and Unorganised sectors.

The public sector in Andhra Pradesh is defined by Central & State Public Sector Undertakings.

Public

Public Sector Undertaking (PSU)/State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) is the back-bone of the planned Economy. Contrary to market-fundamentalists today, investment in this model ensured Independent India did not remain a mere exporter of raw commodities (Neo-Colonialism). It took necessary steps to industrialise and become a modern exporter of manufactured goods. It also set the stage for private manufacturers to gain expertise and eventually scale-up for an international clientele.

Finally, it is important to note that many PSUs are in fact profitable, and should be treated as State Assets (of which Vizag Steel is one example).

“Profits industries by 2004-05:

1.Singareni Calories [Collieries] Company Limited

2.AP Housing Board

3.APGENCO

4.APTRANCO

5.AP Mineral Development Corporation

6.AP Ware Housing Board

7.AP Trading Corporation

8.AP Forest Development Corporation

9.AP Financial Corporation

10. AP Civil Supplies Corporation” [3, 61]

Private

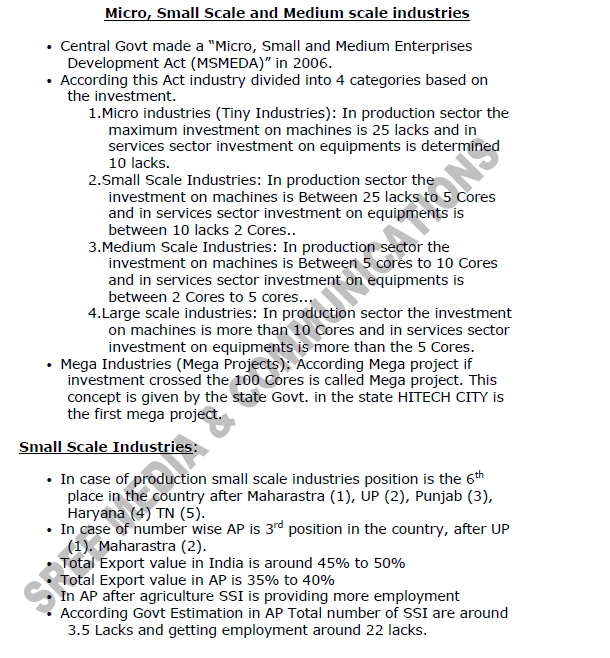

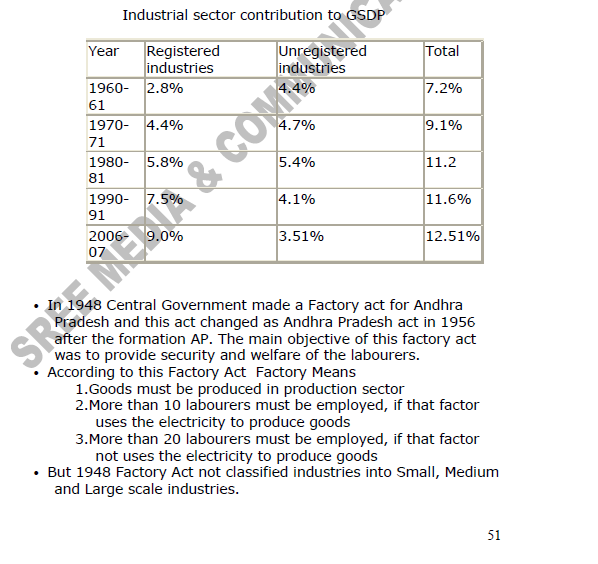

The private sector in United Andhra Pradesh was defined by thousands of independent businesses and merchants. Many of these were registered and incorporated; however, many more were (and are) not. The Industrial sector’s contribution to the UAP State economy was almost 13%.

Although public and private as well as unorganised and organised are the main categories of economic study, the key sectors are Agriculture, Services, and Industry. For the sake of consistency, hyper-modern sectors like Software or Automation won’t be examined. Simply the basic and most consistent aspects will be considered so that a comparison can be studied not only by decade, but even by century given the breakdowns available from the ancient and medieval periods.

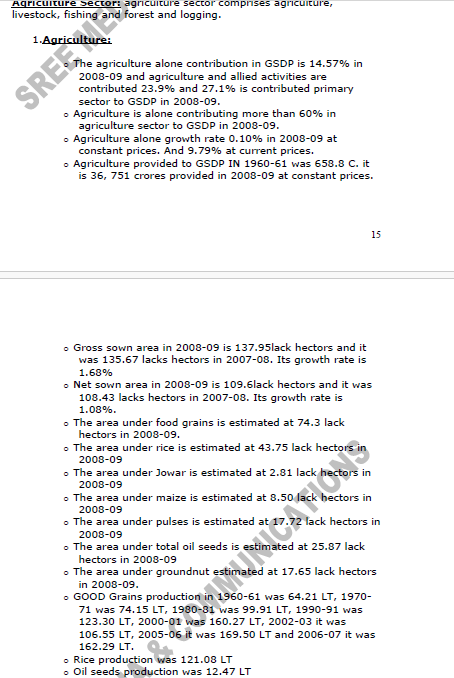

Agriculture

Agriculture is responsible for about 36% of Gross Value added to SGDP. Due to tabulation oddities, it is grouped with Mining (which should be under Industry) in the Primary Sector. The Primary sector includes crops, livestock, aquaculture, forestry, and mining. Despite only accounting for 20 percent of the Indian national GDP, it accounts for 60% of employment. If all those free-market capitalists dreaming of Farm Laws wish to see this occur, they must intelligently plan for the reallocation of human capital to manufacturing and services. This requires not only attracting industry, but also establishing vocational institutes and technical schools.

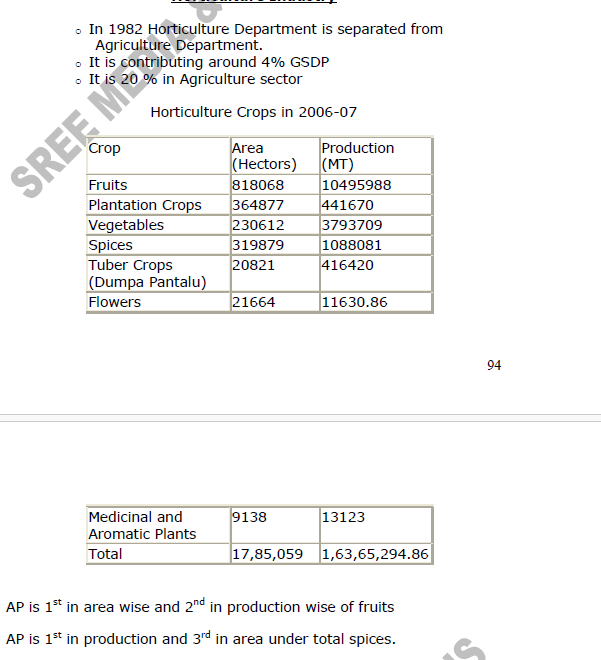

Horticulture

Horticulture is responsible for crop production. The main crops of UAP (described as the Ricebowl of India) are Paddy, Groundnut, Cotton, Sugarcane, Maize, Pulses, Sunflower, Soybean, Wheat, Tobacco, Jowar, Bajra, Ragi (Millet), Castor, Sesamum, Jute, & Safflower. “Ranked #1 in cultivation of Oil Palm, Papaya, Lime, Cocoa, Tomato and Chillies “.

Aquaculture

AP is very strong in Aquaculture. With ~1000 km of coast line, it is prominent in fisheries as well as shrimp and crab. Despite being a pescetarian state, much of this is for internal and foreign export. AP is the top state for Aquaculture (Fisheries & Shrimp), 4th in Meat and Milk.

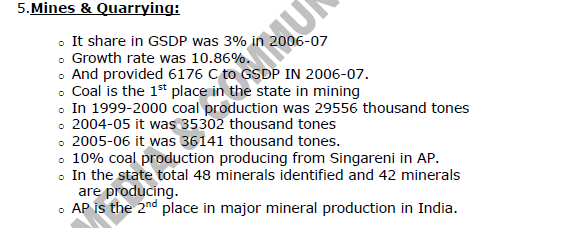

Mining

Singareni Collieries is the best known PSU. Coal Mining is central to an industrial state (yes, even in this era of Renewable Energy). Retaining it as a state asset is pivotal. Zinc & Uranium are other crucial minerals found in AP, along with the famous Diamonds of Kolluru & Pearls of the coast.

Singareni Collieries is the best known PSU. Coal Mining is central to an industrial state (yes, even in this era of Renewable Energy). Retaining it as a state asset is pivotal. Zinc & Uranium are other crucial minerals found in AP, along with the famous Diamonds of Kolluru & Pearls of the coast.

“Andhra Pradesh accounts for 30% kyanite, 31% garnet, 18% titanium minerals, 17% tungsten, 12% bauxite, 15% sillimanite, 8% vermiculite, 13% each limestone & Iron (magnetite), 6% …diamond” Source: Govt of India

Industry

Industry is described as the Secondary. Due to tabulation oddities, Mining and Forestry are not included here. It is responsible for 20% of the economy with Manufacturing proper (sans Electricity & Construction) driving 10% of Gross Value Added. Textiles, Petro-chemicals, Pharmaceuticals, and Electronics are some of the main industries.

Industry is described as the Secondary. Due to tabulation oddities, Mining and Forestry are not included here. It is responsible for 20% of the economy with Manufacturing proper (sans Electricity & Construction) driving 10% of Gross Value Added. Textiles, Petro-chemicals, Pharmaceuticals, and Electronics are some of the main industries.

The textile industry in general, and Handloom in particular, in Andhra Pradesh is in serious need of capital investment or at the bare minimum, patronage. What is the use of all those millions and millionaires if you watch your own state’s heritage fray in threads?!! Financial capital must invest in human capital and CapEx to ultimately preserve Cultural Heritage. Andhra’s Capital Saree is the prime example.

Services

Described under the Tertiary Sector, Services is responsible for approximately 40% of the State’s economy. Software, Finance, Tourism, and Health Services are the predominant segments here. Trade & Repair is about 7%, Hospitality at 2%, Communication & Broadcasting at 8%, Railways at 8%, Real Estate and Professional Services at 8%, and Financial at 5%.

Infrastructure

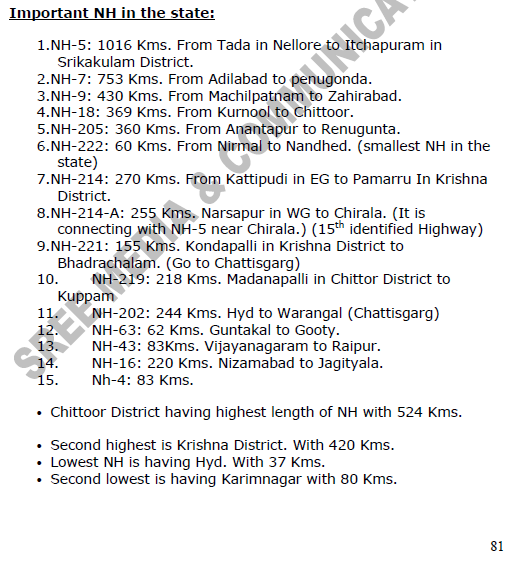

Modern Andhra Pradesh has 6 Airports, with 1 at Bhogapuram slated to be International. It has 4 main ports (Krishnapatnam, Kakinada, Gangavaram & Visakhapatnam). However, the essential component of connectivity is road connectivity. Although slightly dated, here are the main National Highways in UAP.

Connectivity

Dams are another critical aspect of infrastructure. Perhaps nothing symbolises the infrastructure of the state more than Nagarjuna Sagar Dam.

Other notable constructions, include the aforementioned Arthur Cotton Barrage, as well as the Godavari and Krishna Anicuts.

Human Development Index (HDI)

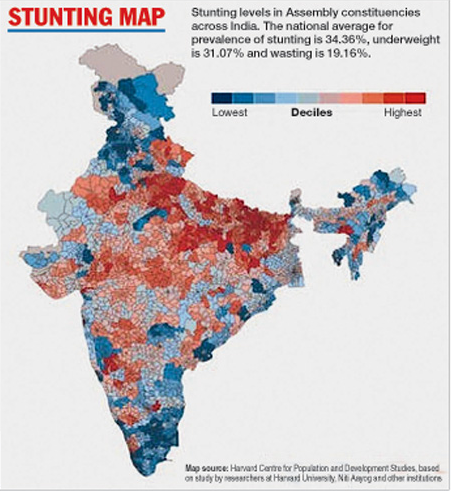

No picture of a State’s economic profile is complete without a look at HDI or at least Malnutrition. As of 2011 (when the last census data was procured), UAP had an HDI rank of 9, with an overall score of ~0.7 . India overall was estimated by the UNDP to have crossed 0.6 (middle HDI) , with 0.8 the typical range for Developed Countries.

Despite immediate reforms after Independence, Andhra State and later United Andhra Pradesh had issues with malnutrition and even cases of starvation. At great public expense (with some critique by bureaucratic bean-counters…), NTR addressed the issue of malnutrition in the 1980s.

“Poverty in AP in 2004-05 is 15%

5.In case of IMR is 11th position out of 17 states.

6.During 1999-05 Real wage rate reduced

7.At the time of 2004-05 in AP total 94% labourers are working in

unorganized sector.

8.Agricultural contribution reduced from 60% in 1950 to 22%.

9.There is more Child Labour problem. It was 14.8% in 1993-94

and it was reduced to 6.6% in 2004-05. It is two times more

than the national level.” [3]

Personalities

Ironically, some of the biggest business houses in Telugu States today are owned not by the orthodox Aarya Vaisya (Komati) community, but by Kamma Naidus, Reddis, and Raajus (Aandhra Kshathriya). Some of the names are controversial while others remain evergreen and celebrated. Without casting judgment on the basis of caste or other criteria, we simply list them out so that people can start to support Aandhras in small and big business. For reasons of simplicity, we have excised from mention Entertainment Families (i.e. Akkineni & Konidela families) as well as political dynasties (Yeduguri, Nara & Nandamuri families). The focus is on independent industrialists.

“Hurun India and M3M India released the list of top billionaires in India for the year 2023. Around 14 persons from Telangana and Andhra Pradesh have achieved respective spots in the list. Out of them, more than 50 per cent are from the pharmaceutical and healthcare sectors while the rest are from infrastructure and construction sectors.” [6]

D.Adikeshavalu Naidu

G.V.K. Reddy (Pharmaceuticals)

G.M.R. Family (GMR Industries (Ports & Airports))

Cherukuri, Ramoji Rao (Eenadu, Ramoji Films, etc)

Kallam Anji Reddy (Dr. Reddy’s Labs)

Kamineni Family (Apollo Hospital)

B.Parthasarathi Reddy (Hetero Drugs)

Ramalinga Raju (formerly of Satyam, now in Medical Industry)

Jay Galla & Family

Chigurupati Krishna Prasad (Granules India (Pharma))

C. Sathyanarayana (Laurus Labs (Pharma))

P.V. Krishna Reddy (Megha Engineering & Infrastructures)

M. Satyanarayana Reddy & Family (MSN Laboratories)

V.C. Nannapaneni (Natco Pharma)

Murali Divi & Family (Divi’s Laboratories (Pharma))

C. Visweswara Rao & Family (Navayuga Engineering)

Mahima Datla

Krishna Chivakula

Contrary to stereotypes, mana Aandhrollu aren’t as big in tech as they ought to be (at least since the downfall of Satyam, and convenient sale to Mahindra…). Of the 800 Richest Indians (Millionaires and Billionaires), 62 made the list from United Aandhra. “In terms of the number of individuals in the list, the pharmaceutical sector accounts for 32% of the richest individuals in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, followed by the food processing industry with 11% and the construction and engineering sector with 8%.” [7]

There are obviously many, many more names we could add; nevertheless, due to space constraints we have kept it as such. Readers are welcome to suggest others in the comments. The real question, however, is how many of these worthies are willing to invest not only in their financial enrichment, but in the cultural enrichment of the state?

With all those crores, millions, and billions, how many of them are supporting AP artisans at Lepakshi or Kondapalli or Etikoppaka, over those “in phoren“? That is a true sign not only of cultural, but economic and political enlightenment.

Conclusion

The closing of Andhra Bank was one of the great insults to the Andhra people that occurred while they were in their usual phillim-addled, caste-coddled mindset. The East India Company was a private Multi-National Corporation, with joint-stock ownership. Invariably the interests of the people are always far from the mind of an MNC. A PSU, on the other hand, is never far from the interests of the people. Meaning: certain key sectors and key industries are better off under public ownership, with remaining major share in the hands of private entrepreneurs. Socialism is ultimately terrible for the economy, however, modern capitalists and dharmic thinkers alike agree that certain key areas are better off under public control. Railways, airlines, and mining are certain key examples of historic market failure. They are typically better off under National or State/Provincial ownership.

As for agriculture, the actual situation in Andhra Pradesh (and India in general) is a matter of controversy. With the decline in its share of not only GDP but in income, agrarian distress has increased. It is not only large landholders (zamindars) and arhatiyas that must be considered, but farm workers who have not been properly redirected to a different sector for wage labour. Development is not merely a matter of statistics and numbers, but it is about balancing economic efficiency with human well-being. It is all fine to seek to modernise and liberalise, but this must be done in a way that plans for the reallocation of resources, even the inhumanly named “human resources”. Failure to do so can have unintended consequences at human expense.

Since 1996, the Liberalisation Reforms exposed agriculture to the Global market, putting small farmers at risk of competition with Big Agro. Many went into debt in order to finance commodity crops like Bt Cotton, and when they failed, they took their lives by taking their own pesticide. Estimates for this Agrarian Distress vary, but it is certainly is in the Tens of Thousands over the past quarter century.

Mismanagement by the government, greed from corporations, and short-sightedness by the citizens means that the basics of Political Economy have been forgotten. Emphasis for Agriculture should be on Subsistence first + Surplus profit, instead of Plantation commodity crops, originating from colonial company rule.

A balance between state and centre, private and public, big business and small business, ensures that everybody gets a share of the pie, all while the pie is growing. Ensuring that independent farmers and industrial giants alike find a way to flourish is the key to prosperity. Andhra Economic Society must aim for balance in all things rather than fall in to free-market fundamentalism (with a firesale of state assets) or disastrous communism (which is the path to tyranny). Neo-Liberalism is the path to Neo-Colonialism.

Wise statesmen will consider the consequences of either system and act accordingly and dharmically to ensure prosperity for all (not just for the privileged few).

References:

- Rao, T.Dayakar. Trade and State Craft in Medieval Andhra: A Reappraisal (600-1600 AD).Delhi: B.R. Publishing. 2016

- Rao, P. Ragunadha. History of Modern Andhra Pradesh. New Delhi: Sterling Publ.2003

- ‘Andhra Pradesh Economy’. Sree Media & Communications. (Accessed 2024)

- Kate, P.V. Marathwada Under the Nizams, 1724-1948, Delhi: Mittal Publications, 1987

- Chakravarthy, Nalamotu. My Telugu Roots. Bolingbrook, IL. BFIS Inc.2009

- “14 Telugus in top billionaires list”. The Hans India.https://www.thehansindia.com › business › 14-telugus-in-top-billionaires-list-789199

- “62 people from Telangana and Andhra make ‘India’s richest’ “. IIFL. list”. https://www.iiflwealth.com/newsroom/in_the_news/62-people-telangana-and-andhra-make-indias-richest-list (Accessed 2024)

I’m a proud Telugu Andhran. I enjoy your portal.

Thank you for your comment, Sheila garu. Welcome to our site.